Νοτιον Ακρον

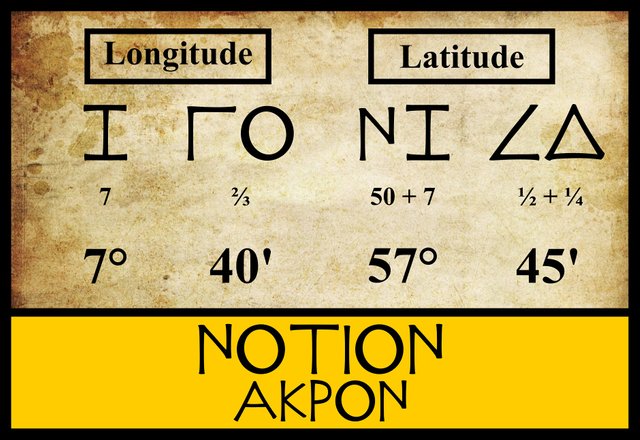

The final landfall in our voyage down the west coast of Ireland, with Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography as our sailing directions, is a headland that Ptolemy calls the Southern Promontory. The three modern editors I am following have located this feature in the same latitude (57° 45') and the same longitude (7° 40'). Karl Müller, however, recorded some variant figures in a handful of the manuscript sources and one of the early printed editions:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | 07° 40' | 57° 45' |

| Σ, Φ, Ψ, 4803, 4805, M | 07° 20' | 57° 12' |

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

4803 and 4805 are two of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. They are Latin translations of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803 and Latin 4805.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which we have met several times before. It was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name, Argentorate.

Ptolemy recorded the name of this feature as νοτιον aκρον [notion akron]: southern promontory, or southern headland. This is a purely Greek name, like βορειον aκρον [boreion akron], or northern promontory the headland at the other end of the west coast:

νότιος, α, ον ... II southern ... south ... southerly. (Liddell 1011)

Why Ptolemy gave Greek names to these headlands is a subject I shall return to in a later article. Not surprisingly, no variant readings are to be found in any of the manuscripts.

Marcian

Karl Müller also edited the writings of another early geographer, Marcian of Heraclea, who flourished in the 4th century of the Common Era, about two hundred years after Ptolemy. Marcian’s Periplus of the Outer Sea includes a brief description of Ireland, but as Müller emended—bowdlerized?—Marcian’s text, I translate from the earlier edition by the French scholar Emmanuel Miller:

At its greatest length, measured from the Southern Promontory to the Rhobogdian Promontory, the Britannic island of Ireland is 2,170 stadia long. Moreover, in breadth, the width of the island between those same promontories is 1,834 stadia. (Miller 103-104)

Müller took exception to the length and the width being measured between the same two headlands (absurde was his Latin comment, which needs no translating), so he emended the second sentence to read:

Moreover, in breadth, the width of the island between the Sacred Promontory and the Rhobogdian Promontory is 1,834 stadia.

The Sacred Promontory, you may remember, is the headland in the extreme southeast of the island.

Müller also emended Marcian’s first figure of 2,170 stadia to read 3,170 stadia.

Goddard Orpen, who followed Müller’s edition of Ptolemy in his own analysis, took issue with Müller here and adequately explained both Müller’s mistake and Marcian’s method:

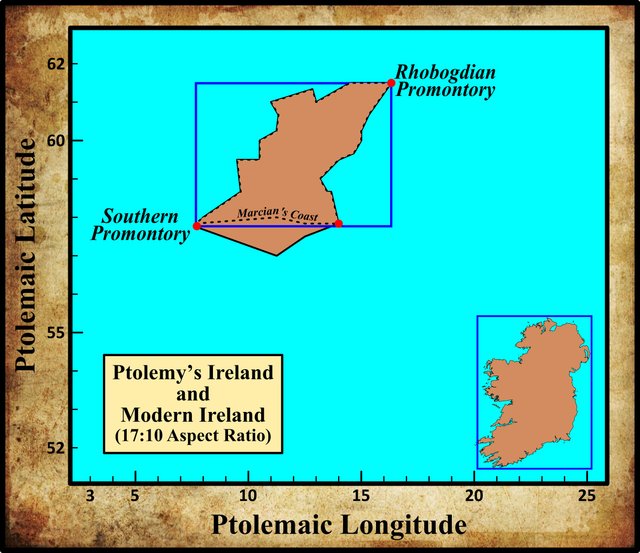

At first sight it may seem strange to measure both the length (longitudo, μηκος) and the breadth (latitudo, πλάτος) from the same two points. The explanation of this is that as the Rhobogdium promontory was at once the most northern and the most eastern point, while the Notium or southern promontory was also the most western point, Marcian takes the difference of longitude between these two points as measuring the length (from west to east) of Ireland, and the difference of latitude between the same points as measuring the breadth (from south to north).

Now, according to Ptolemy, the difference of longitude between the Rhobogdium promontory and the Notium promontory is 8° 40', and the difference of latitude between the same two points is 3° 45'. Taking 250 stadia to one degree of longitude (which is right for the middle parallel of Ireland), and 500 stadia to one degree of latitude (which was Ptolemy’s computation), the sums work out as follows:

8° 40' or 8⅔ × 250 = 2166⅔ stadia.

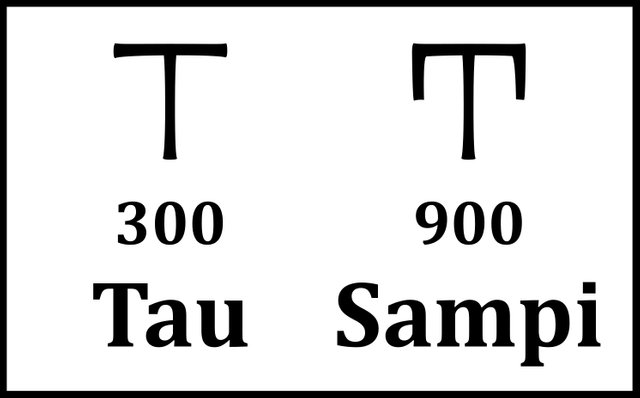

3° 45' or 3¾ × 500 = 1875 stadia.Thus it will be seen that Marcian’s figures yield very nearly (within 5') Ptolemy’s angular measurements. But the discrepancy in the breadth of Ireland, slight as it is, admits of explanation. From a subsequent passage, the figures in which are ingeniously corrected by Müller, it appears that Marcian placed the Notium promontory in lat. 57° 50' instead of in Ptolemy’s 57° 45'. This passage runs : “Occiduum vero ejus promontorium ab aequatore (distat) stadia *8317 (͵ητιζ),” [But its western promontory is *8317 stadia from the equator] and Müller corrects the figures into 28917 (prefixing ͵͵β and replacing the τ with the less familiar sign Sampi = 900, which it somewhat resembles), but strangely applies them to the Sacred Promontory (p. 78, n. 4). Now if we take 28917 stadia as whole numbers for 28916⅔, and divide by 500 stadia, we get 57° 50' as the lat. of the Notium promontory, according to Marcian, instead of Ptolemy’s 57° 45'. This then subtracted from 61° 30', the lat. of the Rhobogdium promontory, gives 3° 40' or 3⅔ as the difference. 3⅔ × 500 = 1833⅓, or in whole numbers 1834, which is exactly Marcian’s figure for the breadth (from south to north) of Ireland. (Orpen 120-121)

So why did Müller emend Marcian’s 2,170 stadia to 3,170 stadia? I have no idea.

The following map has an aspect ratio of 17:10, which is appropriate for the latitude of the real Ireland. (Ptolemy placed Ireland northwest of its true location, in a latitude where the correct aspect ratio is about 20:11, the ratio Ptolemy used in Geography 8:1.) This means that the distance on the ground between two points that are 1 cm apart on the map and lying north and south of each other is approximately the same as the distance on the ground between two points that are 1 cm apart on the map and lying east and west of each other. As you can see, Marcian’s box around Ireland is widest in the east-west direction, whereas a box around the real Ireland is widest in the north-south direction. As we shall see in a future article, Marcian believed that the Southern Promontory was both the westernmost and the southernmost point on the Irish coast, just as the Rhobogdian Promontory was both the easternmost and the northernmost point. This is why he used these two promontories as opposite corners of his box.

This discrepancy between ancient and modern maps of Ireland is something I alluded to in the third article in this series, where I discussed a remark by another geographer, Philemon, who flourished in the 1st century of the Common Era, about one hundred years before Ptolemy. To repeat what I wrote in that earlier article:

In Book 1 of the Geography, Ptolemy cites the obscure geographer Philemon in relation to the size of Ireland:

7: It seems that Marinus himself did not trust the stories of merchants. Certainly, he did not agree with the reckoning of Philemon, who recorded that the length of the island of Ireland was twenty days and twenty nights, since Philemon said that he had heard this from merchants. (Ptolemy 1:11:7, Müller 29)

Berggren & Jones translate the crucial phrase as:

... the longitudinal extent of the island of Ireland from east to west as a twenty days’ journey. (Berrgren & Jones 72)

A few other online translations I consulted agree that Philemon’s estimate was from east to west. But the Greek _το απ’ ανατολων επι δυσμας ἡμερων εικοσι _ could mean from sunrise to sunset for twenty days, rather than from east to west for twenty days. Like the Romans, the Greeks used the terms for sunrise and sunset to indicate the cardinal directions of east and west. In other words, Philemon was referring to the distance that could be covered in a continuous period of twenty days and twenty nights without overnight stoppages. The Irish scholar J J Tierney accepts the received translation, but amends the text to bring out the other meaning:

Neither can we actually say that Philemon visited Ireland. We merely know ... that he had learned from merchants that the length of the island was twenty days’ journey from east to west (we should rather read from north to south since the long axis of the island was thought to run from north to [south] ... It would seem, however, that Philemon’s figure calculated at this rate (twenty-one miles [33 km] per day for twenty days) is reasonably accurate for Ireland. (Tierney 261 ... 262)

Tierney’s disclaimer that Ireland was thought to be longer from north to south than from west to east needs to be qualified, if not rejected outright. It appears that Philemon and Marcian, and probably also Ptolemy, thought that Ireland was longer in the west-east direction. And Pliny the Elder, to name just one other scholar of the ancient world, was of the same opinion. In his Natural History, we read:

Almost thirty years ago, Britain was explored by Roman armies to the area not beyond the Calidonian forest. Agrippa believes the longitude of the island to be 800 miles [~1200 km] and the latitude 300 miles [~450 km], and Ireland the same latitude but 200 miles [300 km] less in longitude. (Pliny 4.102)

Curiously, Pliny’s latitudinal length of Ireland from north to south is quite accurate (~450 km), but his longitudinal width from east to west is almost three times the correct value (~900 km versus ~350 km). In his Ireland and the Classical World, Philip Freeman notes that this conception of Ireland’s form was firmly in the tradition of Strabo and his Greek sources (Freeman 52).

Identity

In the early 17th century, the British antiquarian William Camden identified Ptolemy’s Southern Promontory with Mizen Head at the end of the Kilmore Peninsula, the most southwesterly point on the island. In his description of County Desmond—“Now annex’d, part of it to Kerry and part to Cork”, as Camden’s 18th-century editor Edmund Gibson noted—he described how the west coast of this now-defunct county comprised:

[P]arcels of Land divided from one another by great incursions of the Sea ... Among these Arms of the Sea, are three several Promontories ... The third Promontory, named Eraugh [or Iveragh] lies between Bantre and Balatimore or Baltimore ... this is that Promontory which Ptolemy calls Notium, or the South-Promontory, and is at this day call’d Missen Head. (Camden 1336)

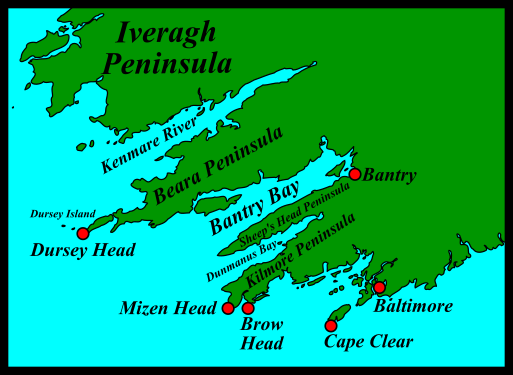

In the preceding article in this series, I included this same quotation and showed how confused Camden’s geography is. Gibson glossed Camden’s Eraugh as Iveragh, which is possibly correct, but a glance at a map shows that Camden was not actually talking about the Iveragh Peninsula, which lies further north, but to the pair of peninsulas known today as Sheep’s Head Peninsula and Kilmore Peninsula. Bantry Bay lies to the north of the former, while Baltimore lies to the south of the latter. Mizen Head lies at the end of Kilmore Peninsula. John Speed’s map of 1610-11 does identify the Kilmore Peninsula as Eragh.

Almost every scholar that has come after Camden has followed his lead and identified Ptolemy’s Southern Promontory with Mizen Head. Among these were the 17th-century Irish antiquarian James Ware and his 18th-century editor Walter Harris:

Notium, or the south Promontory. This Promontory is by Sea-men called MISSEN-HEAD, in the County of Cork. [Others call it Biar-head.] (Ware & Harris 40)

The bracketed comment was added by Harris. I can’t say that I have ever come across that particular name for Mizen Head. Possibly Harris means Bere Head, which would suggest he is thinking of the Beara Peninsula.

Charles Trice Martin also agreed with Camden, identifying Notium Promontorium with Mizen Head, but inexplicably he relocated this headland to Wicklow, Ireland! To be fair, there is a Mizen Head in County Wicklow, on the east coast of Ireland, but the only thing southerly about it is its location in relation to the nearby Brittas Bay.

William Beauford also settled on Mizen Head:

Νότιον ἄκρον or southern promontory. The Romans do not appear to have obtained the Irish name of this cape, but have denominated it from its situation. It was most probably the Ben Moisaimh Beallen and Mullobhaghagh of the Irish, the present Mizen Head. Ware calls it Willen Head, and Camden Bear Head. (Beauford 58)

Beauford must have been consulting different editions of Ware and Camden to the ones I quoted from above, where both Ware and Camden call the headland Missen Head. I never came across Ben Moisaimh Beallen as the origin of Mizen Head. In Irish the headland is usually known as Carn Uí Néid, the Cairn of Neit’s Grandson. Neit was a member of the legendary race of the Tuatha Dé Danann, and the grandfather of Bres, who supposedly died and was buried beneath a cairn at Mizen Head. The story of his death is recorded in The Metrical Dindsenchas. Beauford’s Mullobhaghagh probably refers to Mullavoge, the townland that includes Brow Head (see below).

Several scholars who analysed Ptolemy’s description of Ireland did not bother to identify the Southern Promontory—Goddard Orpen and T F O’Rahilly are among the most notable of these.

I am only aware of three other candidates for Ptolemy’s Southern Promontory, all of them in County Cork:

- Dursey Head

- Brow Head

- Cape Clear

Louis Francis was perhaps the first scholar to identify Ptolemy’s Southern Promontory with Dursey Head, in County Cork. Dursey Head is not actually part of the Irish mainland. It is the headland at the southwestern tip of Dursey Island, a small island at the end of the Beara Peninsula. It is connected to the mainland by a cable car—allegedly the only one in Ireland. Robert Darcy and William Flynn have endorsed Francis’s opinion.

Brow Head is the most southerly point on the Irish mainland. It is not nearly as well known as Mizen Head, which lies less than 4 km to the west of it, on the other side of Barley Cove. In A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, Samuel Lewis identified Brow Head with the Notium of Ptolemy (Lewis 249). The etymologists at Roman Era Names have also opted for this headland—presumably because it best fits the Greek name Ptolemy gave to the promontory:

Νοτιον ακρον (Notion 2,2,4) was ancient Greek for ‘southern promontory’ at Brow Head. Early mariners would surely have noticed the rocks there, in what became a copper-mining area, analogous with Cornwall, because they would have had coloured outcrops.

In my opinion, Mizen Head is a better fit for the headland where the west and south coasts of Ireland meet. There are other candidates, however, which deserve consideration. The most southerly inhabited point in Ireland—including our offshore islands—is Cape Clear. This is also a good fit for Ptolemy’s Southern Promontory and has been proposed before (Malte-Brun 1290 fn).

Even further south than this is the Fastnet Rock, which lies some 7 km southwest of Cape Clear. Its Irish name, Carraig Aonair, means Lonely Rock. This is the most southerly point in Ireland, bar none, and could conceivably have been Ptolemy’s Notion Akron.

References

William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

Louis Francis (editor, translator), Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

Philip Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, The University of Texas Press, Austin (2001)

Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, Second Edition, Volume 1, S Lewis & Co, London (1840)

Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

Conrad Malte-Brun, James Gate Percival (editor), A System of Universal Geography: Or A Description of All the Parts of the World on a New Plan, Volume 3, Samuel Walker, Boston (1834)

Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

Emmanuel Miller, _Périple de Marcien d’Héraclée, Epitome d’Artémidore, Isidore de Charax, etc., ou, Supplément aux Dernières Éditions des Petits Géographes : D’après un Manuscrit Grec de la Bibliothèque Royale _, L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris (1839)

Karl Wilhelm Müller, Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Mizen head, County Cork: Wikimedia Commons, © Ent-ente, Creative Commons License

- Dursey Head: © East Cheshire Ramblers, Fair Use

- Brow Head: Wikimedia Commons, © Richard Webb, Creative Commons License

- Fastnet Rock: © Richard Webb, Creative Commons License

Hello friend, it's good that you're back excellent story I'm going to share I love reading your post greetings and thank you very much, I wish you success

Excellent post dear buddy

Posted using Partiko iOS

Very excellent historical post dear

Posted using Partiko iOS