Ναγναται

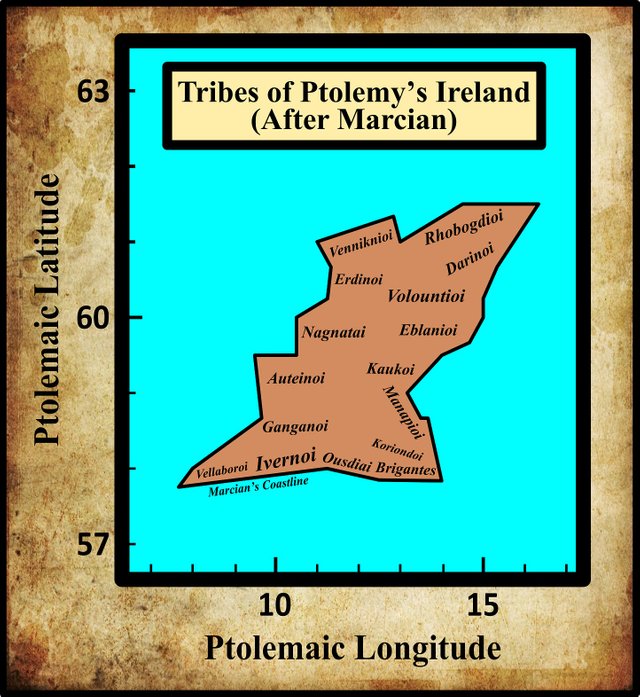

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Resuming our voyage down the west coast of the island, the eleventh tribe we encounter are the Nagnatai (Latin: Nagnatae). Ptolemy places these people immediately south of the Erdinoi.

In his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Karl Müller noted several variant readings of this ethnonym, but some of these differ from one another only in the application of the Greek accents. As the use of these accents was not regularized until the Byzantine era, they are generally considered to be “without authority” (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2, Gnanadesikan 220-221). This reduces the number of variants to two, or possibly three:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MSS | Ναγναται | Nagnatai |

| B, N, V, Z, D | Μαγναται | Magnatai |

| M?, 4803?, 4805? | Μαγναοι | Magnaoi |

| M?, 4803?, 4805? | Μαγνατοι | Magnaτoi |

B is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1404.

D is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1402.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate. According to Müller, this has the Greek reading Μαγνᾶοι [Magnaoi] and the Latin translation Magnatæ, but according to Wilberg, the Greek text reads (or, rather, the Latin translation implies the reading) Μαγνᾶτοι [Magnatoi].

N refers to a pair of Latin manuscripts discovered by the Prussian geographer Konrad Mannert. According to Müller, these preserve the form Μαγνᾶοι [Magnaoi], but according to Wilberg, they actually read (or, rather, the Latin translation implies the reading) Μαγνάται [Magnatai].

V is an edition of Ptolemy’s Geography published in Ulm in 1482 by Lienhart Holle, with the assistance of the cartographer Nicolaus Germanus Donis.

Z is Vaticanus Palatinus Graecus 314, a Greek manuscript from the old Palatinate Library of Heidelberg, which is now part of the Vatican Library in Rome.

4803 and 4805 are two of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. They are Latin translations of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803 and Latin 4805. Müller includes these among the three manuscripts that have the form Μαγνᾶοι [Magnaoi], but these Latin manuscripts do not have the Greek text. They both give the Latin Magnate.

Curiously, Müller opted for Μαγνᾶται [Magnatai] in his critical edition of 1883, even though this is only attested in one Greek manuscript (D), and even that was altered by someone to read Ναγνᾶται [Nagnatai] (Müller 77). T F O’Rahilly, who chose Ναγναται [Nagnatai], noted that:

The form Μαγναται [Magnatai], adopted by Müller, has very little authority. (O’Rahilly 2).

In his 1838 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Friedrich Wilberg adopted the form Ναγνάται [Nagnatai], which is one of the commonest forms. In 1843, Karl Nobbe adopted the similar form Ναγνᾶται [Nagnatai], which is also well represented in the manuscript tradition.

There is no good reason for not following O’Rahilly and accepting Ναγναται [Nagnatai] as the correct form. The substitution of Μ for Ν may be a simple typographical error—these two Greek letters do look alike—or they may reflect some contamination from the Latin Magna (Great). Curiously, Müller’s Magnatai continues to find support in some modern quarters (eg Darcy & Flynn).

Identity

In Ptolemy’s Geography, the Nagnatai are associated with the “city” of Nagnata [Ναγνατα Πολις], which was clearly named for them. In an earlier article in this series, I concluded tentatively:

The identity of Nagnata must remain a mystery. Nevertheless, if I were pressed on the matter, I would opt for the present site of Sligo town. This has the only significant harbour on the stretch of coast between the mouths of the Erne and the Moy, which are in my opinion the best candidates for the two rivers on either side of Ptolemy’s Nagnata. The outer harbour is well protected from the Atlantic by Coney Island, while the mouth of the Garavogue River would have made an ideal location for a trading settlement—not a town or permanent settlement, but a landing place for foreign ships.

In the light of subsequent research, I have not had any reason to alter this opinion.

Earlier scholars have little of substance to add to the debate. William Baxter’s attempts to explain the derivation of the names is marred by his reading of Naguata and Naguatæ, neither of which finds any support in the manuscript tradition—notwithstanding any possible similarity between the Greek letters nu and upsilon (Baxter 181). Nevertheless, Walter Harris dutifully follows in his footsteps. James Ware, however, whose works were edited by Harris, despairs of locating any such city as Nagnata, and is content to surmise that the Nagnatæ inhabited the Country now called the County of Sligo, and possibly also the Town of Mayo (Ware & Harris 43).

Roderic O’Flaherty is as bemused by the names Nagnatæ and Magnati as he is by those of the Savage nations of America (O’Flaherty 23).

William Beauford is satisfied that the Nagnatai inhabited the barony of Carbury in County Sligo, an opinion he bases on the coordinates supplied by Ptolemy for their “famous city” Nagnata. This he tentatively identifies with Drumcliff in the same barony. Drumcliff lies about 8 km north of Sligo Town, which is also in the barony of Carbury (Beauford 56-57, 60).

Goddard Orpen follows Müller in adopting the form Magnatai, and merely notes that they are of course associated with the town of Magnata (Orpen 119). The latter, he suggests, may be related to the Irish word magh (plain), which we find in the county name Mayo (Maigh Eo, The Plain of the Yew) and in the native name of Moyne Abbey in the same county. (Orpen 118, Joyce 425). This etymology is also found in Fr Charles O’Conor’s Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres (Fr O’Conor lvi). Orpen and Fr O’Conor are assuming that the people were named for the city, whereas it was surely the other way round.

Coming down to the 20th century, we have the following analysis from T F O’Rahilly:

Nagnatae These were apparently located in North Connacht. Cóiced Connacht as a name for the western province is a late creation, which could not have come into existence until after the Connachta (Goidels from the Midlands) had conquered the province. An earlier name for it was traditionally remembered as Cóiced (n)Ól nÉcmacht (or Nécmacht). [Footnote: The n of nécmacht is invariable ... But it is none the less possible that the n of nécmacht was originally the initial of the word, and not the eclipsing n-.] We also find fir Ól nÉcmacht (i.e. the men of Connacht) and tuatha Ól nÉcmacht. None of the attempts that have been made to explain the phrase can be regarded as satisfactory. As to what Ól may mean I have no suggestion to offer; but it possible that Nécmacht is related to Ptolemy’s Nagnatae. Unfortunately we have no fixed point to argue from, for it is probable that both Nagnatae and Ól Nécmacht have been corrupted in transmission. (O’Rahilly 11-12)

Elsewhere, O’Rahilly surmises that the Goidelic conquest of Connacht took place “At an early period, which we have no means of determining” (O’Rahilly 173). This may have been before Ptolemy’s time, but it was certainly long after the time of Pytheas of Massilia, who, according to O’Rahilly, was probably Ptolemy’s main source of information about Ireland (O’Rahilly 39-42). O’Rahilly’s suggestion of a possibly corrupt link between Ptolemy’s Nagnatai and the native Ól Nécmacht had already been made in the 18th century by Charles O’Conor, grandfather of the Fr Charles O’Conor mentioned above (O’Conor 178)

Notwithstanding O’Rahilly’s warning, the temptation to link Nagnatai and Connacht has been too great for some scholars to resist. Before O’Rahilly’s time, the French scholar André Berthelot had confidently made the connection:

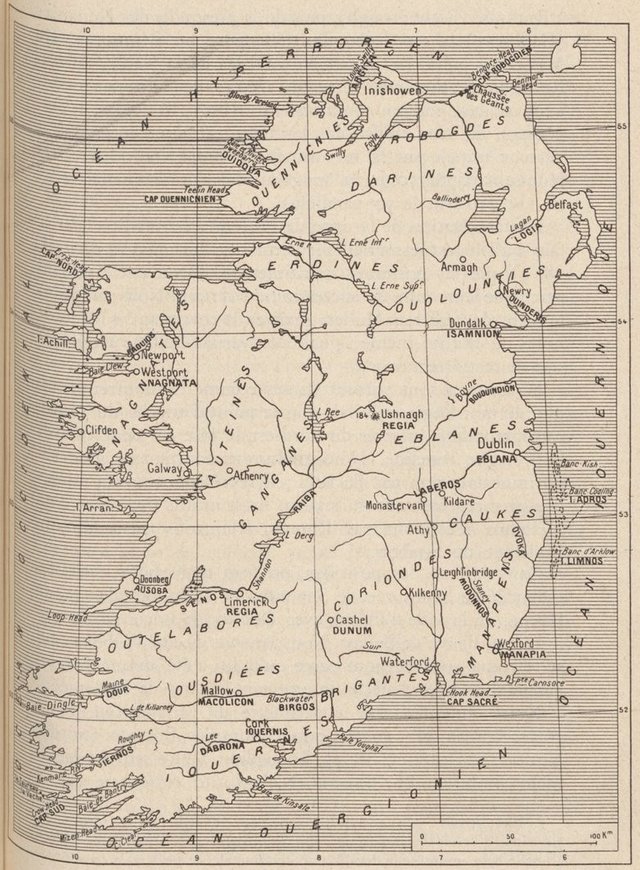

On the western side, to the south of the Vennicnians lived the Erdinians, whose name seems to be preserved in those of the River and Loughs of Erne. Below them, ie to their south, were the Nagnatians, whose name persists in that of Con-nachta (Connaught); their city Nagnata might have been on Clew Bay (Westport, Newport ??). (Berthelot 244)

The Irish scholar Patrick Weston Joyce, writing in the 1860s, had also expressed confidence in this connection:

The oldest writer by whom Irish places are named in detail is the Greek geographer, Ptolemy, who wrote his treatise in the beginning of the second century. It is well known that Ptolemy’s work is only a corrected copy of another written by Marinus of Tyre, who lived a short time before him, and the latter is believed to have drawn his materials from an ancient Tyrian atlas. The names preserved by Ptolemy are, therefore, so far as they are authentic, as old at least as the first century, and with great probability much older.

Unfortunately very few of his Irish names have reached our time. In the portion of his work relating to Ireland, he mentions over fifty, and of these only about nine, can be identified with names existing within the period reached by our history. These are Senos, now the Shannon; Birgos, the Barrow; Bououinda, the Boyne; Rhikina, Rechra or Rathlin; Logia, the Lagan; Nagnatai, Connaught; Isamnion Akron, Rinn Seimhne (now Island Magee), i. e. the point of Seimhne, an ancient territory; Eblana, Dublin; and another (Edros) to which I shall return presently. (Joyce 79)

As usual, the contributors to the toponymic website Roman Era Names have come up with a novel etymology for this ethnonym (which they give in the masculine plural, a form not attested by any of the manuscripts):

Ναγνατα (or Μαγνατα) πολις (Nagnata 2,2,4) was a settlement at Sligo, of the Ναγνατοι (or Μαγνατοι) people. An element -gnata naturally means either or both of ‘known’ and ‘born, descended from’ (Delamarre, 2003:180-181) in a range of ancient languages, as also discussed here. So, if Na- meant ‘not’, the Ναγνατοι might have been ‘unknown’ or ‘unrelated’ people, implying that that region on the west of Ireland was ethnically or linguistically different from further east. (Roman Era Names)

The independent researcher Martin Counihan agrees with some of this:

In the region of County Sligo there was, according to Ptolemy, a tribe of Nagnatae. Their town, Nagnata, was at or near Sligo town. The prefix na- is the negative, “not”. The second part of the name, -gnatae means (and is cognate with) “known”. So, the Nagnatae were “the unknown people”.

But the name may be understood in two alternative ways: on the one hand, Nagnatae could mean that they were a people with exceptional qualities: in Old Irish, the word gnáth can mean “known” in the sense of “customary”, or “usual”, so Nagnatae could be a complimentary name meaning “special” or “exceptional”.

On the other hand, and much more probably, Nagnatae could simply mean that these people were unknown to the voyagers whose information was drawn on by Ptolemy. So, Nagnatae was not really a name at all, just an indication that nothing could be said about the inhabitants of that coast. This interpretation would be consistent with the fact that the name Nagnatae does not appear to have survived into historical times. (Counihan 11-12)

Conclusions

I have nothing of value to add other than to note that the scholarly consensus is that Ptolemy’s Nagnatai, whether corrupted or not, is probably of Celtic provenance.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- André Berthelot, L’Irlande de Ptolémée, in Revue Celtique, Volume 50, pp 238-247, Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris (1933)

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1904)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 1, Longmans, Green, & Co, London (1910)

- Marcian, Karl Müller (editor), Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland to which is subjoined a Dissertation on the Irish Colonies Established in Britain with Some Remarks on Mr Mac Pherson’s Translation of Fingal and Temora, George Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- Fr Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Sligo Port: © Firefly, Fair Use

- André Berthelot’s Map of Ptolemy’s Ireland: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public Domain

- Benbulben, County Sligo: © Ian Mitchinson, Fair Use