Μαναπια Πολις

The next landfall in our tour of Ptolemy’s Ireland is Μαναπια Πολις, or Manapia City, a settlement on the eastern coast in the vicinity of the mouth of the River Modonnos. In the previous article, I identified the Modonnos with the River Slaney, but other identifications have been mooted over the centuries—most notably the Avoca and the Liffey. In addition to these, there are other rivers that flow into the Irish Sea on this stretch of coastline—the Vartry and the Dargle, for example—but I am not aware of any researchers linking any of them to Ptolemy’s Modonnos. Before we try to identify Manapia City, there is another question we need to investigate.

Polis

In his description of Ireland, Ptolemy lists eleven settlements. The Greek word he uses to designate these landmarks is πολις [polis], which generally denotes a city or a citadel. But did Ireland have cities in ancient times? It is even doubtful whether Ireland had towns or villages in Ptolemy’s day, let alone cities. The ancient Greeks had separate words for each of these smaller settlements:

| Greek | English |

|---|---|

| πολις | city |

| κωμη | village |

| ἀστυ | town |

In most Latin editions of Ptolemy’s Geography, πολις is translated as either urbs or oppidum. Both terms are used by Müller in his translation of Ptolemy’s description of Ireland: urbs once, and oppidum nine times, including Manapia oppidum. (The eleventh settlement, Isamnium, is given as a promontory in several manuscripts and Müller tentatively agrees).

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| urbs | a walled town, a city |

| oppidum | a town |

Interestingly, Lewis and Short also note that Caesar used the term oppidum to describe a fortified wood or forest among the natives of Britain:

When the Trinobantes had been placed under protection and secured from all outrage at the hands of the troops, the Cenimagni, the Segontiaci, the Ancalites, the Bibroci, and the Cassi sent deputations and surrendered to Caesar. From them he learnt that the stronghold [oppidum] of Cassivellaunus was not far from thence, fenced by woods and marshes; and that he had assembled there a considerable quantity of men and cattle. Now the Britons call it a stronghold [oppidum] when they have fortified a thick-set woodland with rampart and trench, and thither it is their custom to collect, to avoid a hostile inroad. (De Bello Gallico 5:21)

Considering the importance of cattle in ancient Ireland, it is likely that such fortifications were used here as well as in the sister isle, and in fact we know this to be true. The word bawn, an Anglicization of the Irish badhún, describes such a structure. But Ptolemy’s Irish settlements were presumably permanently occupied places and not temporary fortifications hastily thrown up in time of war. So what were they?

Goddard Orpen, who also cautions against a too literal interpretation of these terms, offers the following analysis:

Of course in the sense in which the word oppidum was applied in Romanised Gaul or Britain, it may be said that there can have been no towns in Ireland in Ptolemy’s time. His πόλεις must be regarded as referring to the principal duns, cashels, cathairs, or raths, inside of which the chieftains of tribes and their attendants dwelt in either dry-stone clochauns or round wicker-work huts (Orpen 126)

dun: (Irish: dún) a fortress, a royal residence

cashel (Irish: caiseal) a stone fort

cathair (Irish: cathair) a ringfort, a circular stone fort

rath (Irish: ráth) a ringfort, an earthen rampart, a circumvallation

clochaun (Irish: clochán) a dry-stone hut with a corbelled roof

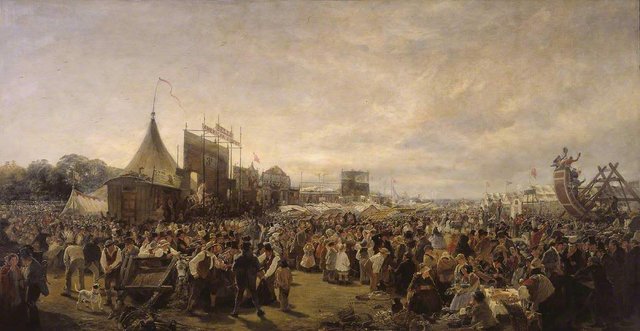

The Fair of Carman

In my opinion, Orpen has omitted an important item from his list: a marketplace or trading emporium. We know that in early medieval Ireland, important fairs were held at regular intervals in a number of prominent places. The name for such a social gathering or assembly was aonach (or óenach), an event in which politics, trade, sport and religion were combined. A few of the more ancient and important fairs came to be known as the Great Fairs and have been compared to the Pan-Hellenic Games of ancient Greece (ie the Olympic, Isthmian, Nemean and Pythian Games).

Among these Great Fairs was the Fair of Carman. Eugene O’Curry has left a description of this fair in the second of his lectures On the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish, which was delivered at the Catholic University of Ireland on 28 May 1857. It was held, he tells us,

anciently for the province of Leinster ... I allude to the Fair of Carmán (now Wexford), which was revived, A.D. 718, by Dunchadh, King of Leinster, and last celebrated in A. D. 1023, by Donagh Mac Gillapatrick. There is preserved in the Book of Leinster (a MS. known to have been compiled about the year 1150), a great part of a celebrated old poem upon this fair; which I believe to have been contemporary with the last celebration of the feast, if not of even a more ancient date. (O’Curry 38-39)

He then briefly recounts the legendary origins of the Fair of Carman:

Three men who came from Athens, and one woman; these were the three sons of Dibad, son of Dorcha, son of Ainches; Dian, Dubh, and Dothur were their names; and Carmén was the name of their mother. The mother, wherever she went, blasted and blighted everything by spells, charms, and incantations; and it was by magical devastation and dishonesty that the men dealt out destruction. They came into Erinn to bring evil upon the Tuatha Dé Danann, by blighting the fertility of the country against them. The Tuatha Dé Danann were incensed at this; and they sent against them Ai, the son of Ollamh, on the part of their Poets; and Cridenbel on the part of their Satirists; and Lug Laeban, the son of Caicher, on the part of their Druids; and Becuillé on the part of their Witches, to pronounce incantations and satires against them; and they never parted from them until they forced the three men over the sea, leaving behind them their mother Carmén as a pledge that they should never again return to Erinn; and they also swore, by the divinities which they adored, that they would not return as long as the sea flowed around Erinn. Their mother, however, soon died of grief of her hostage-ship; and she requested of the Tuatha Dé Danann that they would institute a fair and games in her honour wherever she should be buried, and that the fair and the place should receive and retain her name for ever; and hence Carmán, and the Fair of Carmán, And the Tuatha Dé Danann observed this Fair as long as they occupied Erinn. (O’Curry 39)

Most of our knowledge of the Fair of Carman is derived from a long 11th-century poem preserved in the Book of Leinster and the Book of Ballymote. The one thing we do not know for certainty, however, is the location of the fair. Some scholars place it in the south of County Kildare, but since the 18th-century there have been those who see in Ptolemy’s Manapia an early reference to Carman, which they are happy to locate on or close to the present site of Wexford City. In defence of this location, O’Curry included in his second lecture another explanation of how the Fair of Carman received its name:

Another version is that old Garmán had followed the seven cows of Eochaidh Belbuidhé King of [Kintyre in Scotland] which had been carried off by Lena the son of Mesroeda the son of Datho the King of Leinster ... Old Garmán discovered them at the south side of Datho’s Dun; and he killed Lena ... And old Garmán then carried away his kine to Magh Mesca [that is, Mesca’s Plain, where Wexford now stands]; and she, Mesca, was the daughter of the great chieftain Bodhbh, of the hill of Finnchaidh, in the mountain Monach, in Scotland; she had been carried off by old Garmán in a trance; and Mesca died of shame in this place; and her grave was made there, namely, the grave of Mesca, daughter of Bodhbh. And the four sons of King Datho overtook old Garmán at this place and old Garmán fell by them there; and they made his grave there; and so he begged of them to institute a Fair (or games of commemoration) for him there, and that the fair and the place should bear his name for ever: and hence the Fair of Carmán, and old Carmán got their names. And the people of Leinster observed this fair in tribes and families, down to the time of the monarch Cathair Mór [in the second century]. (O’Curry 39-40)

The Irish name for Wexford Harbour is Loch Garman.

The Fair of Carman was undoubtedly of ancient standing. The poem from which O’Curry quotes claims that it was instituted 580 years before the Incarnation of Christ, though this must be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, if it did take place near Wexford, it might very well have been of long standing. In the preceding article in this series I pointed out how fitting such a setting would have been for a trading emporium. What better place for the Irish to assemble and trade with foreign merchants than in a sheltered harbour in the south-east corner of the island, the point closest to the continent?

The Fair of Carman was held every three years between 1 August and 6 August. The first day of August was Lughnasa, or the Festival of Lugh, an important feast in pagan Ireland, marking the start of harvest. The first week of August would have been an ideal time for trading with continental merchants, when produce was fresh and plenty and before the deterioration of the weather brought the sailing season to an end.

And if it be objected that the Fair of Carman was a purely Irish assembly—of national importance, perhaps, but hardly of international standing—one need only quote some verses preserved in the Book of Leinster:

Three markets were held within its borders:

A market for food; a market for live cattle; [and]

The great market of the foreign Greeks,

In which are gold and noble clothes.

The slope of the steeds; the slope of the cooking;

The slope of the assembly of embroidering women.

(O’Curry 47)

P W Joyce, who believed the fair was held somewhere in the south of County Kildare, had no illusions about the economic role of the fair:

Special portions of the fair-green were set apart for another very important function—buying and selling. We are told that there were “three [principal] markets : viz. a market of food and clothes: a market of live stock and of horses; while a third was railed off for the use of foreign merchants with gold and silver articles and fine raiment to sell.” There was the “slope of the embroidering women,” who actually did their work in presence of the spectators. A special space was assigned for cooking, which must have been on an extensive scale to feed such multitudes. (Joyce 501)

But Where was Carman?

A strong case can be built against the Wexford-Carman identity. For a start, the city of Wexford was founded by Norsemen in the early 9th century, but the Fair of Carman is said to have been held for the last time in 1023 (or 1079 according to the Annals of the Four Masters).

In his exhaustive dictionary of Irish place names, Onomasticon Goedelicum, Edmund Hogan marshals all the evidence, making this entry one of the longest in the book—too long to quote in full in this article. Here, however, are some of the highlights:

Carman: Óenach Carman ... was on site of town of Wexford ... was in South of county Kildare ... “was really in the present County Carlow” ... was in County Kildare ...

Hennessy, in language too long to quote, twice expresses his disedification at “such an acute topographer” as John O’Donovan’s equation of Carman with (Loch) Garman, “for which there is no authority” ...

I do not wish to deprive the Faithche of Wexford, now called the Fáith, or Fair-green, of the glories of the ancient Oenach Carman fully described in the Books of Leinster and Ballymote. Yet all the evidence seems to show that Carman was a large plain on the banks of the Burren and the Barrow, which unite at the town of Carlow ... a place at the geographical, social, political, and military centre of Leinster, near the royal palace, which was the rendezvous of the warriors of Leinster when about to march against their foes, and near, or not far from, the five great tribal divisions of the Province ... from this central place also they could quickly send a “punitive” expedition if Munster or Meath were mean enough to invade their borders during the Óinach; that shows it ought to have been there; but, then, Irish eccentricity might have held the Oinach Carman at Loch Carman, at the town of Wexford, where O’Donovan and O’Curry place it ...

Óinach Carman in ancient and in comparatively modern times was always and only held by kings, sub-kings, and chiefs, whose lands met near the junction of the Burren with the Barrow. This is clear from the description of it in the Books of Leinster and Ballymote ... as well as from the Irish Annals ...

Carman was one of the 7 chief cemeteries of Erin, at it were many meeting-mounds, 21 raths, 7 mounds, 7 plains or fields (without a house) reserved for the Óinach; it may be said that cúan (harbour), ráth-lind (bounteous water), and bruachaib (banks), applied to Carman, would not suit the town of Carlow; I think so: the tide goes higher than St. Mullins, and from New Ross to Athy (10 miles [16 km] North of Carlow) the Barrow is navigable by barges ...

A writer in the Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland 2:399, 1:316, got very near the real Carman: “The Rath or moat of Carman or Mullaghmast near Ballytore, 6 miles [10 km] East of Athy, its site is a gently sloping hill crowned by an extensive rath, and near it are 16 mounds, on which the elders of the States of South Leinster sat in council, these mounds are held in veneration by the peasantry.” (Hogan Carman)

The bulk of the evidence certainly seems to imply that the Fair of Carman was held somewhere in the vicinity of Carlow Town, and not at Wexford. It should be remembered, however, that the fair was discontinued—allegedly—in the 2nd century and not revived until 718 CE, so there is always the possibility that upon its revival it was moved to a more favourable location. We know of at least one instance of a fair being moved: the Aonach Colman was traditionally held at Lynally in County Offaly, but it was transferred to the site of the present day town of Nenagh, 65 km away:

Aonach Cholmáin where the men of Munster were buried, was held in the parish of Lann Eala or Lynally in the Barony of Ballycowan, King’s County [Offaly], about a mile to the south-east [recte south-west] of Tullamore, in the ancient tuath of Feara Ceall, and province of Meath; this district was originally in Munster, from which it was taken by Tuathal Teachtmhar A.D. 130. Aonach Cholmáin would appear to have been the original site of the Mór-Aonach of Munster, which was afterwards transferred to Aonach Teite, called in later times Aonach Urmhumhan (“the fair of Ormond”) and now Nenagh (an Aonach) in Co. Tipperary. Aonach Cholmáin then became merely a tribal assembly of the Feara Ceall under O’Maolmhuaidh or O’Molloy. (Stopford Green 40)

Nevertheless, even if the Fair of Carman had nothing to do with Ptolemy’s Manapia, this does not mean that there was not an important trading emporium at the mouth of the River Slaney in ancient times. I still think that this is where Manapia is to be found.

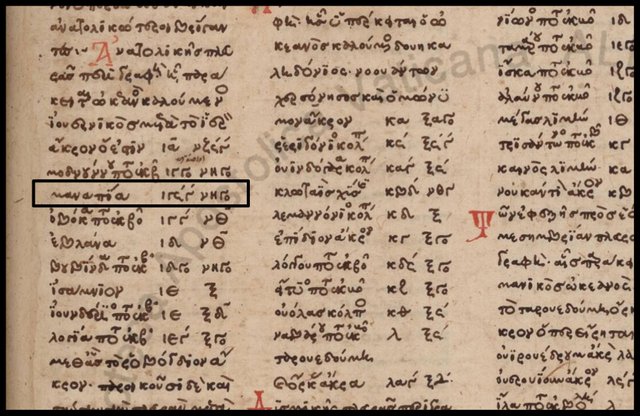

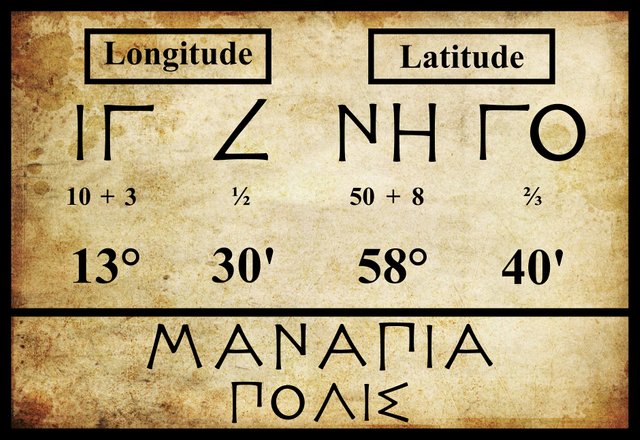

Data

The principal editions and early manuscript sources all agree on the latitude and longitude of Manapia. Ptolemy places it in the same latitude as the mouth of the River Modonnos, but 10 minutes of arc to the west. In Ptolemy’s estimation, 10' of longitude at this latitude corresponded to about 7.7 km (Ptolemy 1:7:1). Wexford Harbour and Dublin Bay are approximately of these dimensions.

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller | 13° 30' | 58° 40' |

| Wilberg | 13° 30' | 58° 40' |

| Nobbe | 13° 30' | 58° 40' |

| Vaticanus Graecus 191 | 13° 30' | 58° 40' |

Manapia has been identified with numerous different locales over the centuries. Its close proximity to the mouth of the River Modonnos is generally retained, but as we have seen, there has never been a consensus as to the identity of this river.

| Wexford Town | Carman | Dublin | Wicklow Town | Near Enniscorthy | Near Bray |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camden (1607) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ware (1654) | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | O’Conor (1766) | - | - | - | - |

| Lewis (1837) | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | Orpen (1894) | - | - | - | - |

| Martin (1910) | - | - | Martin (1910) | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | Mac an Bhaird (1991-93) | - |

| - | - | Francis (1994) | - | - | - |

| Darcy & Flynn (2008) | - | - | - | - | - |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 57

If the Modonnos was indeed the Slaney, then Manapia must have been Wexford—or an earlier settlement in the same area. If, however, the Modonnos was the Liffey, as Louis Francis surmises, then Manapia could only be Dublin, or its ancient predecessor. These are the only plausible identifications. There were no other prominent settlements on this part of the coast that lay about 8 km west of a river mouth or the opening of a bay.

Etymology

Ptolemy’s spelling of Manapia is common to almost all surviving sources, and there is no reason to suspect that it has suffered any corruption.

| Greek | English |

|---|---|

| Μαναπια | Manapia |

Manapia has long been recognized as a good Celtic name, one that was probably derived from the name of the local populace, the Manapii (Μαναπιοι). As O’Rahilly notes:

The name of the Manapii has long been recognized as a variant of that of the Menapii, a Gaulish tribe who were seated on the Meuse and on the Lower Rhine.

Orpen uncovered an interesting piece of topographical information that warrants consideration:

The name Manapia may also be equated with one form of that of the Isle of Man ... and Pliny expressly calls the island Monapia. The Irish form of this name [Manainn] may possibly survive in a place called Carrigmannan on the right bank of the Slaney about five miles [8 km] above Wexford. (Orpen 125)

Charles Trice Martin (290) identified Manapia with Wexford, or Wicklow. In defence of the latter, one could quote Edward Williams Byron Nicholson:

I turned to Ptolemy, who is believed to have written about A.D. 120, and found that he mentions the Μανάπιοι as dwelling on the E. coast of Ireland (II. 2 §8). He also speaks of Μαναπία πόλις (§7), which is identified with Wicklow, and only a few miles N. of Wicklow is Clonmannan (Clon = meadow). There is also a Carrigmannan on the Slaney about 5 miles above Wexford (Joyce, Irish Names of Places, 2nd S. 294). (Nicholson 9)

I will have more to say on this subject when I come to discuss Ptolemy’s Menapii. For the time being I am going to assume that the Modonnos is the River Slaney and that Manapia was a trading emporium in the vicinity of Carrigmannan.

References

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Louis Francis, Ptolemy’s Geographia: Books I and II, Distributed by the University of Oxford under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, (1994)

- Edmund Hogan, Onomasticon Goedelicum Locorum et Tribuum Hiberniae et Scotiae: An Index, with Identifications, to the Gaelic Names of Places and Tribes, Hodges, Figgis & Co, Dublin (1910)

- P W Joyce, A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland, Longmans, Green & Co, London (1906)

- Charlton T Lewis, Charles Short, A New Latin Dictionary, Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York (1891)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Edward Williams Byron Nicholson, Keltic Researches: Studies in the History and Distribution of the Ancient Goidelic Language and Peoples, Henry Frowde, London (1904)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Eugene O’Curry, On the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish: A Series of Lectures, Volume 2, Williams and Norgate, London (1873)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Alice Stopford Green, The Making of Ireland and Its Undoing: 1200-1600, Maunsel and Company, Ltd, Dublin (1920)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Caesar: Wikimedia Commons, © Gautier Poupeau, Creative Commons License

- Donnybrook Fair: Art UK, Erskine Nicol (artist), Photo Credit: Tate, Creative Commons License

- Eugene O’Curry: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Manapia (Vaticanus Graecus): © Vatican Library, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, Folium 139r, Fair Use

- Carlow Town: Bing Maps, © 2018 Microsoft, Fair Use

- Carrigmannan, County Wexford: © David Hawgood, Geograph Ireland, Creative Commons License

thanks, for sharing such type of history.

@upvote & @resteem done

I am waiting for your supper and classical history about Ireland.

interesting. Upvote for You

Excellent illustrations to understand much better your post congratulations.

It is very interesting to see how many of the Irish traditions were born.

Learning post.

Thank you buddy for sharing irish history..

Love you❤️❤️❤️❤️

nice post about history of ireland

@resteemed

its an intersting post, thanks for share.

@upvote & @resteem done

Excellent friend great job thank you for sharing such an interesting story of great quality well

Wonderful history of Ireland.Very informative post! Thank you for continuing your hard work and knowing us with the history Of IRELAND 😊