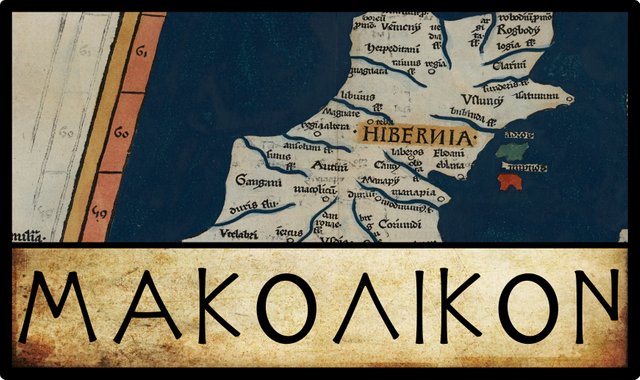

Μακολικον

In his Geography, Claudius Ptolemy records seven inland “cities” in Ireland. The fourth of these is called Μακολικον [Makolikon]:

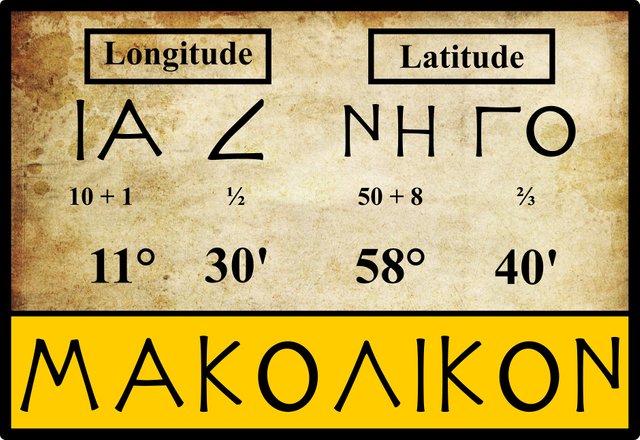

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Μακολικον | Macolicum | Makolikon | 11° 30' | 58° 40' |

Source: Nobbe 66, Wilberg 103, Müller 80

No variant readings of this name have been recorded by Ptolemy’s modern editors Friedrich Wilberg (1838) or Karl Müller (1883). Nor are any alternative coordinates found in the manuscript sources.

Identity

Makolikon is another problematic toponym. No consensus has ever been reached on its identity. It is not even clear whether the name is a native Celtic name or a Greek translation.

In his description of County Longford, the English 17th-century antiquarian William Camden writes:

One side of this County is water’d by the Shanon, the noblest river in all Ireland ... It rises in the County of Trim ... from whence, as it runs Southward, it grows very broad in some places, like a Lake. Then, it contracts it self into a narrow stream, and after it has made a lake or two, it gathers-in it self again, and runs to Macolicum, mentioned in Ptolemy, now called Malc, as the most learned Geographer G. Mercator has observed. (Camden 1374)

Camden’s 18th-century translator Edmund Gibson comments:

But Sir James Ware declares, that he could not find any place of that name; unless it may be Milick by the river Shannon; which is in the County of Galway. (Camden 1374)

James Ware was an Irish antiquary of the 17th century. Writing about a generation after Camden, he states:

Macolicum Mercator and Camden call this Place Malc; but I am utterly at a Loss where to find a Place of that Name. I am of Opinion it is Melick, which is washed by the River Shanon, and lies in the County of Galway. Nor do the Names sound much unlike. (Ware & Harris 41)

Ware’s editor, the Irish antiquary Walter Harris adds a lengthy comment to this, in which, as usual, he draws upon the Welsh Celticist William Baxter:

But Ptolomey places this among the maritime Cities; which may give some doubt; since we never read that Melick was remarkable for any thing but a Franciscan Convent founded in latter Times. Baxter has another Conjecture, that Kilkenny is the Macolicum of Ptolomey, and that it was called so from the Irish Words Mach-Collach, i. e. the Field of the Cornel-trees, and he labours to deduce the modern Name Kil-kenny from the same Fountain (viz.) Coill, a Cornell-tree, and Cean or kend, a Head or Hill. But this overthrows the popular Notion, that Kilkenny took its Name from St. Canic or Kenny, to whom the Cathedral there is dedicated. Nor can Baxter’s notion possibly square either with the Situation or Description of Macolicum in Ptolomey. (Ware & Harris 41)

In every extant manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography, Makolikon is listed among the inland cities, not the maritime cities as Ware asserts. Perhaps he meant to write mediterranean? Otherwise it is hard to disagree with Harris’s criticisms of Baxter’s fanciful etymology. Baxter suspects that St Canice never existed (Baxter 162), and while it is true that many so-called saints are of dubious historicity, St Canice is probably not one of them. He is referred to by name by Adomnán, who was writing in the late 7th century, less than a hundred years after Canice’s death. Of course, this does not preclude the possibility that Makolikon refers to Kilkenny—simply that the two names are not related.

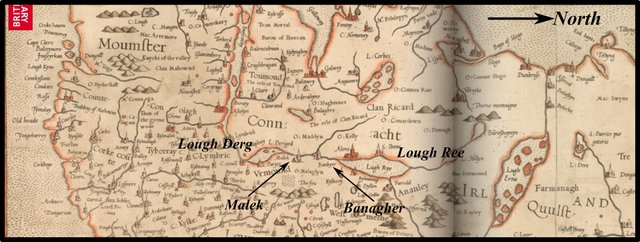

And what of Mercator’s Malc? Mercator’s 1564 map of Ireland has a town called Malek on the left bank on the Shannon between Lough Ree and Lough Derg, south of Banagher. The location of this town does correspond closely to that of Macolicum on his 1584 map of Ptolemy’s Ireland. I can only assume that this is the Malc Camden is referring to. But what town does Mercator mean by Malek? As Ware surmised, he can only be referring to Meelick, which is actually on the other side of the Shannon. But as Harris noted, the history of this place only goes back to the Middle Ages. There is, however, an important ford at this point in the Shannon, so the position has probably been of strategic importance for centuries. In 1203, the Anglo-Norman warlord William de Burgo constructed a castle in the vicinity to secure the ford. The Franciscan friary of which Harris writes was established in 1414.

The Irish name of the place, Míleac, is interpreted as meaning low marshy ground (Joyce 121), which is certainly appropriate. But it is hard to connect this toponym to Ptolemy’s Makolikon. Pace Ware, I do not think the names sound much alike.

Matters are further confused by William Camden’s remarks following his discussion of Malc:

Soon after, the Shannon is received by another broad lake (called Lough Regith,) the name and situation whereof make it probable, that the City Rigia (which Ptolemy places in this Country) stood not far off. (Camden 1374-1375)

This implies that Camden placed Malc somewhere along the stretch of the Shannon north of Lough Ree, not south of it, where Mercator clearly located Malek. Robert Darcy and William Flynn have interpreted Camden to be referring to some place:

On Shannon in Co. Longford between Roosky and Lanesborough, roughly Cloondara, Co. Longford. (Darcy & Flynn 57)

I think it is easier to simply say that Camden made a mistake: Camden’s Malc and Mercator’s Malek both refer to Meelick.

Kincora

In 1789, the Irish architect William Beauford offered a novel suggestion:

Μακολικον Mercator and Camden will have this city to be Malc or Milick on the Shannon, but no such name exists, Baxter thinks it Kilkenny. By its situation according to Ptolemy, it was most probably the Cancora of the Irish, the capital and residence of the chiefs of Thomond, situated near Killaloe, where there still remains a large rath or intrenchment. (Beauford 70)

Kincora is best known today as the birthplace of Brian Boru, the most famous High King of Ireland. Its remains now lie buried within the town of Killaloe in County Clare, on the River Shannon. The rath Beauford refers to, however, is probably Béal Bóramha, or Brian Boru’s Fort, which lies about 1.5 km upstream at the point where the Shannon emerges from Lough Derg. It is often confused with Kincora itself. Kincora is thought to have been built as a stronghold against the Norsemen in the early 9th century, and there is no evidence that its history goes back any further than this. However, as in the case of Meelick, it does command the high ground overlooking another important ford in the Shannon, so it may have been of strategic importance since very early times. Kincora was levelled in 1119 by another High King Turlough O’Conor.

The experts at Roman Era Names have explored the possibility that Ptolemy’s Μακολικον is Greek, not Celtic, while at the same time offering a possible Celtic etymology as an alternative:

Μακολικον πολις (Macolicon 2,2,10) was probably near Limerick, where a strong candidate is Ireland’s largest hillfort at Mooghaun, source of a famous gold hoard. In Greek the name would mean something like ‘destroys in battle’, from μαχη [makhe] ‘battle’ and ολεκω [olekō] ‘to destroy, to kill’, with spelling changes Χ to Κ and Ε to Ι perhaps due to a Latin intermediate. In Celtic it could mean something like ‘stony fields’, from Irish macha ‘milking yard’ (hence machair ‘fertile plain’) and lecc ‘stone’. (Roman Era Names)

Mooghaun is certainly old. Mainstream archaeologists date it to the Late Bronze Age around 950 BCE. I, of course, do not accept any such chronology. There was no Bronze Age, and there were no post-glacial pre-Celtic inhabitants of Ireland. The first post-glacial settlers of this country were the Priteni Celts, who probably arrived no earlier than 750 BCE. The so-called Bronze Age actually refers to the time of the Laginian Celtic colonization around 250 BCE, which took place after Ptolemy’s principal source of information visited the country (O’Rahilly 1-42). So Mooghaun, as it now stands, is probably too late to be Ptolemy’s Makolikon. The name is of uncertain origin, but it is only superficially similar to Makolikon.

Limerick

Robert Darcy and William Flynn have opted for Limerick itself, believing Ptolemy’s Makolicon to have been a place of assembly and a trading emporium (Darcy & Flynn 64). The modern city of Limerick dates from the Viking settlement of about 812 CE on King’s Island in the Shannon, but there is evidence of earlier occupation of this site. The very name King’s Island, however, suggests a link with another of Ptolemy’s inland cities, ἑτερα Ῥηγια [hetera Regia], or Another Regia. The Old Irish word for king is rig, so Ptolemy’s Regia may be a Greek transliteration of an early name for King’s Island. It is possible, however, that the name King’s Island was only bestowed on the island after the building of King John’s Castle in the 13th century. Nevertheless, I find it a more convincing match for Another Regia than for Makolicon. It also has to be said that Another Regia is a better geographical fit, assuming that Ptolemy’s Sēnos is the River Shannon. (Darcy and Flynn relocated the Sēnos to Galway Bay, and identified Ptolemy’s Dour with the Shannon.)

The Rock of Cashel

Goddard Orpen offers yet another candidate:

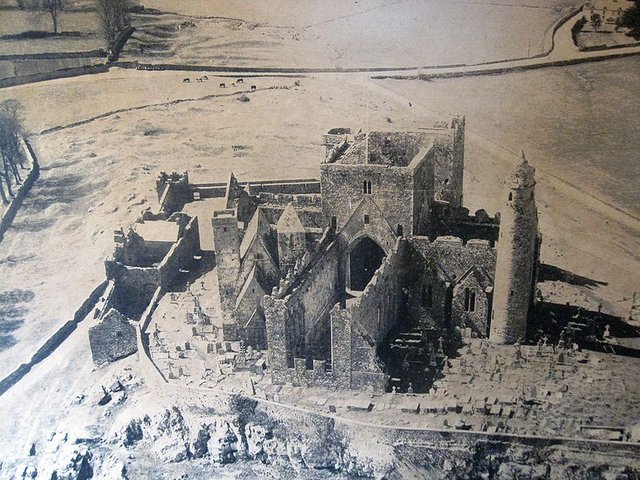

Ptolemy appears to place the Οὐσδίαι [Usdiai, a Celtic tribe] in the counties of Tipperary and Kilkenny ... The town called Μακολικον was probably in this territory, and may possibly have been the Rock of Cashel, which must always have been an important stronghold. (Orpen 122)

The Rock of Cashel was for centuries the royal seat of the Kings of Munster, but there is no evidence that its history extends beyond the 5th century of the Common Era, when it became the capital of the Eóganachta. The latter were a late Celtic people, who had not yet colonized Ireland when Ptolemy’s principal source visited the island around 325 BCE (O’Rahilly 184-192). Nevertheless, the location of Cashel does seem a good fit for Ptolemy’s coordinates, especially if the last two of Ptolemy’s inland cities, Dounon and Ivernis, are identified with Dinn Righ (near Leighlinbridge, County Carlow) and Ard Nemid (on Great Island in Cork Harbour). Because the Rock of Cashel is a National Monument, it is impossible for the site to be properly excavated, so Orpen’s claim that it must always have been an important stronghold cannot be verified. It is, nevertheless, plausible.

Mallow

In his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Karl Müller notes:

According to Camden, Macolicum is Malc (a name unknown on today’s maps) in County Longford; according to Ptolemy’s map, it lies in that region where Mallow is now found. (Müller 80)

Charles Trice Martin, writing nine years later, concurs (Martin 289). Other than the vague similarity of the names, there is really not much to commend Mallow as a plausible candidate for Ptolemy’s Makolikon. The town grew up around the Anglo-Norman castle, which is said to have been built by Prince John (later King John of England) in 1185, during his First Expedition to Ireland.

Clonmel

More recently, Alan Mac an Bhaird has suggested that Ptolemy’s Makolikon may refer to Clonmel in County Tipperary. I have not yet read Mac an Bhaird’s article so I do not know how strong his case is. Like Cashel, which lies about 20 km north-northwest, Clonmel is in the right geographical location to be considered a genuine candidate. According to William P Burke’s History of Clonmel, however, the town is of medieval origin:

It is to the Danes that we are to look for the first beginnings of the history of Clonmel. Making their way of the Suir to its navigable limit, the islands in the river afforded a position to hold their stocks and carry on their barter with absolute security. The home of the O’Phelans, Greenane, was close by, and with them as chiefs of the district the principal exchange of wine, iron, arms, and personal ornament would naturally be made. Tradition indeed has constantly traced the origin of Clonmel to the Danes. (Burke 4-5)

And Finally

If pressed, I would tend to side with Goddard Orpen’s choice of the Rock of Cashel. Taking a hint from Roman era Names, I might surmise that machaire, or something like it, lies behind Ptolemy’s makoli. The interchange of l and r is common in the Celtic languages, a process known in phonology as dissimilation (Thurneysen §§ 192-193). The Rock of Cashel does lie in the middle of a lowlying plain. Perhaps the original name was something like Plain of the Rock. But this is all idle speculation. Even if Makolikon is related to machaire, it could refer to any number of places in central Ireland.

Macolicum was included in Denis Diderot famous Encyclopédie of 1751:

Macolicum: (Géographie) ville de l’Hibernie dans les terres, selon Ptolémée, l. II. c. ij. Est-ce Malek de nos cartes modernes ? nous n’en savons rien.

Macolicum: (Geography) inland city of Ireland, according to Ptolemy, Book 2, Chapter 2. Is this the Malek of our modern maps? We know nothing about it. (Diderot 802)

Little has changed in 250 years!

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William P Burke, History of Clonmel, N Harvey & Co, Waterford (1907)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Denis Diderot: Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, First Edition, Volume 9, André le Breton, Michel-Antoine David, Laurent Durand & Antoine-Claude Briasson, Paris (1751)

- Patrick S Dinneen, An Irish-English Dictionary, New Edition, Irish Texts Society, Dublin (1927)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 3, M H Gill & Son, Dublin (1901)

- Alan Mac an Bhaird, Ptolemy Revisited, Ainm: Bulletin of the Ulster Place-Name Society, Volume 5, pp 1-20, UPSN, Belfast (1991-93)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Images

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Ireland: Gerardus Mercator (1564): British Library, Fair Use

- Killaloe: Site of Kincora: Imagery © 2019 DigitalGlobe, Map Dato © 2019 Google, Fair Use

- Brian Boru’s Fort: Standard YouTube License, Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- King’s Island, Limerick: © Donald Stunden, Fair Use

- The Rock of Cashel: © Allgau, creative Commons License

- Main Street, Mallow: Public Domain

- Clonmel, County Tipperary (West Gate): National Library of Ireland, Eason Photographic Collection, Public Domain

- Rock of Cashel (1970): © Rackmount-guy, Creative Commons License

@harlotscurse You have received a 100% upvote from @intro.bot because this post did not use any bidbots and you have not used bidbots in the last 30 days!

Upvoting this comment will help keep this service running.

Very good historical chronological post dear ...love you