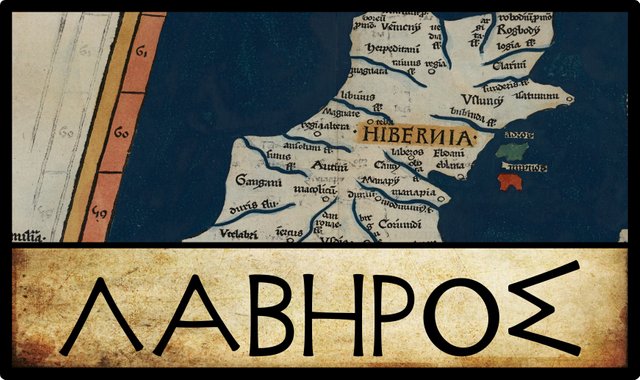

Λαβηρος

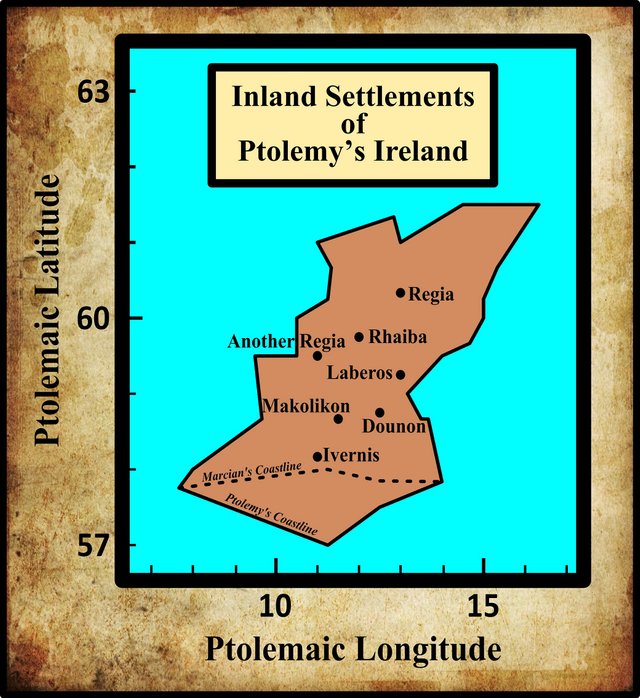

In his Geography, Claudius Ptolemy records seven inland “cities” in Ireland. The third of these is Λαβηρος [Labēros]:

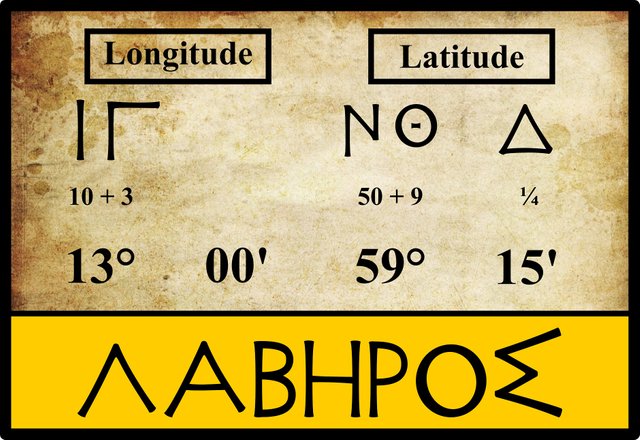

| Greek | Latin | English | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Λαβηρος | Laberus | Labēros | 13° 00' | 59° 15' |

Source: Nobbe 66, Wilberg 103, Müller 80

No variant readings of this name have been recorded by Ptolemy’s modern editors Friedrich Wilberg (1838) or Karl Müller (1883). Nor are any alternative coordinates found in the manuscript sources.

Killare Castle

Ptolemy’s Labēros has been identified with a handful of possible candidate sites. In his description of Meath, the 17th-century British antiquarian William Camden writes:

The remaining part of the Country of the Eblani, was formerly a Kingdom, and the fifth part of Ireland; call’d in Irish Mijh, and in English Methe, and by Giraldus Midia and Media; possibly, because it lay in the very middle of the Island. For they say that Kil-lair, a Castle in these parts (which seems to be Ptolemy’s Laberus, as the name itself intimates) is as it were the Navel of Ireland; and Lair in Irish [ie lár] signifies the middle. (Camden 1369)

Killarecastle is now a townland a stone’s throw from the Hill of Uisneach, the traditional centre of Ireland. The village of Killare has little to recommend it as a possible choice for Ptolemy’s Labēros other than its central location close to this historic spot. The Irish name, Cill Áir, Church of the Plague or Church of the Slaughter, is surely not pre-Christian. Some early sources suggest that the original form of the name was Cill Fháir, and while the meaning of the second element is uncertain (fáir), the presence of Cill again suggests that the name cannot date back to Ptolemy’s time. The castle at Killare was erected by the Anglo-Norman warlord Hugh de Lacy in 1184 during his conquest of Meath (Annals of Ulster). It was sacked and destroyed by the Irish in 1187 (Annals of the Four Masters). Little remained when the site was visited by the architect and stonemason Basil T Stallybrass early in the 20th century:

A good motte, with ditch and well-preserved bank on counterscarp; no bailey. No stone castle. (Armitage 339)

Kells

Half a century after Camden, the Irish antiquarian James Ware offered a new suggestion as to the true identity of Ptolemy’s Labēros:

LABERUS Perhaps this Place may be Cenanus or Kenanuse, now in process of time come to be commonly called Kells in Meath. Antiently it was reckoned among the Cities of best Account, Joseph Molesius calls it Ampreston; but I am at a Loss where to find such a place. Camden_ takes it to be Killair in West-Meath. But I must leave the talk to others to make a more satisfactory Inquiry into this City. (Ware & Harris 41)

Kells is certainly a place of ancient standing, though whether it existed in the time of Ptolemy is much to be doubted. It lies on the Slige Assail, one of the five royal roads that allegedly connected important sites in early Ireland (in this case Tara, seat of the High Kings of Ireland, and Rathcroghan, seat of the Kings of Connacht). But the history of the Five Great Roads is not well known. It has even been suggested that they are of medieval rather than ancient provenance. See The 5 Great Roads of Ancient Ireland: Fact or Medieval Fiction? for further comment.

Joseph Moletius is a reference to Giuseppe Moletti, a 16th-century geographer and polymath from Messina in Italy. His Geographia Ptolemaei is still extant. He identifies Labēros as Amprestom. This enigmatic name can also be found in an Italian translation of Ptolemy’s Geography by Girolamo Ruscelli. Like Ware, I too have no idea what the provenance of this toponym is.

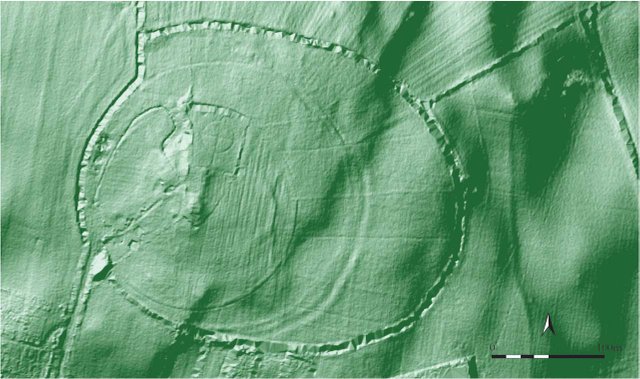

Before it became a prominent Christian centre, Kells was already steeped in ancient history. In 2013 the remains of an ancient fortress were uncovered by archaeologists at the summit of the Hill of Loyd about 2 km to the northwest of the town centre. This discovery improves ever so slightly its claim to be the Labēros of Ptolemy’s Geography.

Tara

In the middle of the 18th century, James Ware’s editor Walter Harris criticized Camden’s opinion and turned, as was his wont, to the Welsh Celticist William Baxter for an alternative identification of Ptolemy’s Labēros:

Camden takes it to be Killair in West-Meath, a Castle so called, which stands in the Center of Ireland, Lair signifying in Irish the Middle or Navell. But how a Castle can be reckoned among the Cities of best Account is difficult to conceive. Baxter conjectures that it was a Place where Councils or Parliaments were held; for that Lhavar in the British Language signifies Concio, or Sermo, as Lavra does in Irish. If this be admitted to carry any Weight, then Tarah antiently called Liath-truim may put in its Claim to be the Laberus of Ptolemey; for there the Monarchs of Ireland held their Courts and public Assemblies. (Ware & Harris 41)

This sounds much more plausible. The Hill of Tara is one of the most significant archaeological sites in the country. It was reputedly the seat of the High Kings of Ireland—the capital of ancient Ireland, if you like—though this is often regarded as a late and learned myth with no basis in actual history. In the Dindsenchas, however, we are told that Tara (or Temair) was known as Druim Leith, Liath’s Hill, in the time of the Nemedians after Liath mac Laigne Lethanglas, who first cleared the site, and as Druim Caín [Caín’s Hill] in the days of the Fir Bolg, after the son of the High King of Ireland Fiachu Cendfindán. If T F O’Rahilly’s model of early Irish history is correct, the Nemedians and the Fir Bolg were the Belgae, a Celtic people who colonized Britain and Ireland from the Continent around 500 BCE. Although these old tales must be taken with a grain of salt—Druim Leith and Druim Cáin have simpler explanations—Tara was surely in existence when Ptolemy’s principal source, conjectured by O’Rahilly to have been Pytheas of Massalia, visited Ireland around 325 BCE.

According to tradition, Tara was abandoned by the High Kings in 568, when Diarmait mac Cerbaill died. A traditional story explains how Tara was cursed by the Christian Saint Ruadhan following a dispute with Diarmait, and this was why none of Diarmait’s successors occupied the hill. But the abandonment of Tara was probably related to the onset in 541 CE of the Justinian Plagues, known in the Irish annals as Mortalitas Magna, or the Great Dying. There was also a global climate catastrophe in 535 CE, possibly caused by a significant meteoritic impact event. Together, this double whammy created the perfect storm that collapsed the Roman Empire, reduced Europe’s population by as much as 90%, and triggered the Dark Ages (Ginenthal 388 ff).

As Harris notes, Liathdrom (or Druim Leith, Liath’s Hill, or Grey Hill) was an ancient name for Tara (Connellan 246), but it would be difficult to connect this with Ptolemy’s Labēros. Baxter’s etymology is, for once, quite convincing. It has been recently supported by the expert contributors to the website Roman Era Names:

Λαβηρος πολις (Laberos 2,2,10) may be the Hill of Tara. The name probably meant ‘talking place’, because there was a pan-European word (possibly from PIE *lab- ‘to lick’) exemplified by Irish labar ‘talkative, boastful’ and its Celtic cognates, but also by German labern ‘to talk at length’, Dutch labben ‘to chatter’, English blabber, Latin labrum ‘lip’, and Greek λαβρος ‘furious’. Ireland is famous for its great writers and talkers, but also for its ring-forts (called ráths) reviewed by Fitzpatrick (2009). “There is great use among the Irish to make great assemblies together upon a Rath or hill, there to parley” (Edmund Spenser, 1596, vol 6, p 628). The cultural tradition for such gatherings, across many countries and from the Stone Ages into modern times, was investigated by Allcroft (1927, 1930).

Robert Darcy and William Flynn have recently endorsed this identification. William Beauford, writing in 1789, was in no doubt:

Λαβηρος. This city is supposed by Ware to be Cenanus or Canenus, the present Kells in the county of Meath. It is evidently the celebrated Tara or Teamhra, called also Labhradh. On the hill of Tara still remain some circular raths and other remains, of antiquity. (Beauford 70)

I am not aware of any source for his claim that Tara was also called Labhradh.

Other Candidates

Goddard Orpen only briefly mentions Labēros in connection with one of the fifteen Celtic tribes enumerated by Ptolemy:

The Καῦκοι [Kaukoi], who are placed below the Eblani ... Λάβηρος [Labēros], somewhere in the vicinity of Glendalough, appears to have been their chief seat. (Orpen 126)

Louis Francis associates Labēros with another tribe, the Darinoi, but does not hazard a guess as to what place it might be.

Karl Müller makes two novel suggestions:

Laberus according to Camden is Killair Castle in the Kingdom of Meath; according to Ptolemy’s map, it lies in that area of Queen’s County where the town of Athy is now to be found; unless it is Bray on the coast. (Müller 80)

Athy is actually across the county boundary in Kildare. It lies close to Castle Rheban, which Camden identified with another of Ptolemy’s inland cities, Rhaiba. As Müller notes, Bray lies on the coast, so it cannot possibly be the inland city of Labēros.

Finally, one might mention Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, who has suggested that Ptolemy’s Labēros was near the modern city of Port Laoise.

In my opinion, the Hill of Tara is the obvious choice for Ptolemy’s Labēros. Its position is approximately correct, its great age and important standing in ancient Ireland are indisputable, and it is quite plausible that Λαβηρος is related to the Old Irish labar, indicating a parliament or place of debate. If Λαβηρος is not Tara, then what is? It would be inexplicable if Ptolemy’s description of Ireland failed to mention such a significant landmark as Tara.

References

- Ella Sophia Armitage, The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles, John Murray, London (1912)

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Owen Connellan (translator), The Annals of the Four Masters: Translated from the Original Irish of the Four Masters by Owen Connellan, with Annotations by Philip Mac Dermott and the Translator, Bryan Geraghty, Dublin (1846)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Ger Dowling, Exploring the Hidden Depths of Tara’s Hinterland: Geophysical Survey and Landscape Investigations in the Meath–North Dublin Region, Eastern Ireland, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, Volume 81, pp 61-85, Cambridge University Press (2015)

- Ptolemy, Louis Francis (editor, translator), Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 4, Forest Hills NY (2012)

- Ali Isaac, The 5 Great Roads of Ancient Ireland: Fact or Medieval Fiction?, Wordpress.com (2018)

- Marcian, Karl Müller (editor), Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Giuseppe Moletti, Geographia Claudii Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Vincentius Valgrisius, Venice (1562)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Girolamo Ruscelli, Geografia di Claudio Tolemeo Alessendrino, Gli Heredi di Melchior Sessa, Venice (1599)

- Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, Ptolemy’s Celtic Italy and Ireland: A Linguistic Analysis, in David N Parsons & Patrick P Sims-Williams (editors) Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe, University of Wales, CMCS Publications, Aberystwyth (2000)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Hill of Loyd, Kells (Geophysical Scan): © The Prehistoric Society 2015, Fair Use

- The Hill of Tara: Getty Images, Fair Use

- The Stone of Destiny at Tara: © August Schwerdfeger, Creative Commons License

Hello friend another great written excellent thanks for the contribution I love your posts without a doubt I will share it in my blog good job congratulations

@harlotscurse You have received a 100% upvote from @botreporter because this post did not use any bidbots and you have not used bidbots in the last 30 days!

Upvoting this comment will help keep this service running.