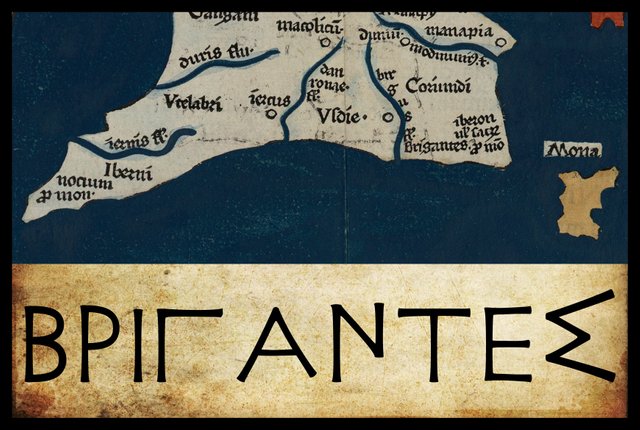

Βριγαντες

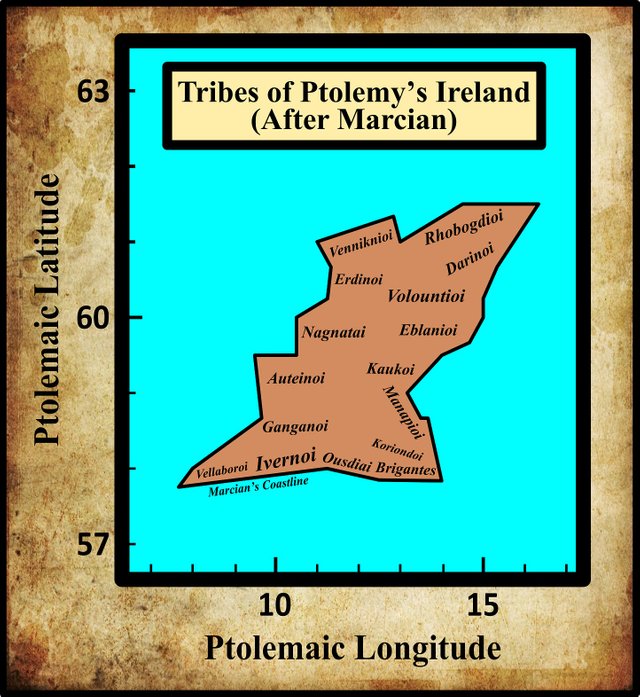

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen native tribes. Beginning, as before, in the southeast corner of the island and proceeding in a counterclockwise direction, the first of these are the Brigantes. These people are described as lying to the east of the Ivernoi, who are placed on the south coast of the island, and to the south of the Koriondoi, who are placed on the east coast.

Variants

In his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Karl Müller notes only one variant reading of this tribal name:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MS | Βριγαντες | Brigantes |

| Σ, Φ | Βρισαντες | Brisantes |

| X | Βριγαντας | Brigantas |

Σ and Φ are two manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 and Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r.

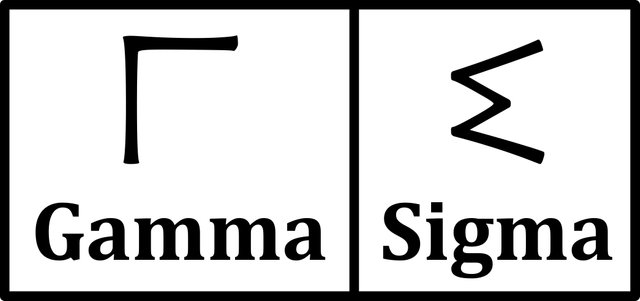

The first of these variants can be safely dismissed as a transcriptional error. There is some slight similarity between the Ptolemaic forms of the Greek letters gamma (g) and sigma (s), so there is nothing unusual in their being occasionally confused.

The second variant is not actually noted by Müller, but it is clearly legible in Vat Gr 191 and has been noted by other students of the Geography. Why Müller, who includes Vat Gr 191 among his sources, omits it I cannot say. Although there is not much similarity between the Ptolemaic forms of alpha and epsilon, their lowercase forms, introduced in the Middle Ages by Byzantine editors, are quite similar and could easily be mistaken for each other.

That Βριγαντες [Brigantes] is the correct form will be clear from the following analysis.

Brigantes

The identity of Ptolemy’s Brigantes has been established beyond all conjecture by students of the Geography. Ptolemy also locates a tribe of Brigantes in northern Britain. Karl Müller thought that these were not actually related:

Above, we surmised that this name, well known in Britain, is perhaps not applicable to Ireland. (Müller 78)

T F O’Rahilly, however, had no doubt that the British and Irish Brigantes were related:

Finally we have the Brigantes, in South Wexford, whom it is hardly possible to disassociate from the Brigantes of Britain. At the time of the Roman conquest the latter were located in what is now the north of England; but it is permissible to suppose that at an earlier period they had dwelt further to the south, and that they had moved northwards as a result of the displacement of population caused by later invasions of the south and south-west of Britain from the Continent. Inasmuch as the British Brigantes belonged beyond question to the Belgic (not the Pritenic) section of the population of Britain, we are safe in assuming that that section of them which settled in Co. Wexford belonged to the Builg or Érainn. (O’Rahilly 34)

He goes on to identify these Irish Brigantes with the Uí Bairrche, a Celtic tribe located in this part of the country in historical times:

The Uí Bairrche, whose original home was in South Wexford, may be taken to be the historical representatives of Ptolemy’s Brigantes. their traditional ancestor is Dáire Barrach ... their descent from Dáire can only mean that ... the Uí Bairrche regarded themselves as Érainn. Bairrche in Uí Bairrche might be genitive of Celt[ic] *Barrekā, fem[inine], while Barrach could represent *Barrekos. With this is to be compared the British deity-name *Barreks, identified with Mars in a Latin dedication M(ARTI) BARREKI found at Carlisle, in the territory of the Brigantes. These names are obviously to be connected with Ir[ish] barr, W[elsh] bar, ‘summit’, and would mean ‘the high god’, ‘the high goddess’. So the Brigantes take their name from *Brigantī, ‘the high goddess’ (whence W[elsh] Braint, the name of a river in Anglesey), of which the Irish counterpart is Brigit (goddess and river name), < *Brigentī; in inscriptions found in the territory of the Brigantes her name is latinized Brigantia. (O’Rahilly 37-38)

Goddard Orpen had already made the connection between the Brythonic Brigantes of northern Britain, Ptolemy’s Irish Brigantes, and the Celtic goddess Brigit:

Finally on the south side we have the river Βίργος [Birgos], in the position of the Barrow (Ir. Berbha), and the people called Βρίγαντες [Brigantes] in the south-eastern corner. The pagan Irish had a goddess Brigit long before their Christian descendants rejoiced in a saint of that name. This name Brigit, genitive Brigte, implies a primitive Brigentis, which may be equated with the goddess Brigantia, whose name appears in Roman inscriptions found in the country of the Brigantes in England, and with the Gaulish Brigindo ... There is certainly no good ground for dissociating the name Brigantes from the goddess Brigit, but if we suppose that the Irish people of that name were an off-shoot from the well-known people of the same name who stretched across Britain, north of the Humber and the Mersey, we introduce a Brythonic element into Ireland which has not, I think, been hitherto recognised. (Orpen 123-124)

Orpen, however, was not the first to suggest a British element among the peoples of ancient pre-Goidelic Ireland. In the late 18th century, William Beauford had already drawn such a conclusion, though many of his ideas are impossible to accept today:

Βριγαντες. Ware makes these the inhabitants of the counties of Carlow, Kilkenny, and the Queen’s County [Laois]. But no such name is mentioned by the Irish. The Romans therefore probably denominated them from their neighbouring river Brigus or Bargus, if they did not mistake Brigus for Brigantes, a nation in Britain. They seem to be the ancient inhabitants of the county of Waterford, called by the Irish Hy Breoghan, and the inhabitants Breaghnach or Breoghnach, that is Breathach or Britons. Admitting therefore that they extended farther inland, they might be the aboriginals from Britain, before the arrival of the Ernai, Heremonii, and other Gothic [recte Goidelic] tribes. But of this there is no certainty. However that the Breoghnach were Britons, is in some measure evinced from the mountains near which they dwelt in the county of Waterford, being denominated Cummeragh or Welsh Mountains to this day. (Beauford 63-64)

And Beauford was not the first either. Going back another half century to 1745, we find the following description in Walter Harris’s edition of The Whole Works of James Ware (The passage in square parentheses is Harris’s gloss):

Brigantes, a People so called. They inhabited the Countries now called the Counties of Carlow, Kilkenny, and Queen’s County. [These People are esteemed to be a Colony from a People of the same Name in Yorkshire, and are said to have retired into Ireland upon the Invasion of the Romans in the Reign of the Emperor Vespasian, about the Year of Christ 76, and in the Government of Petilius Cerealis in Britain; and they are said “to have fled into Ireland, some for the sake of Ease and Quietness, others to keep their Eyes untainted with the Roman Insolence, and others again, that they might not lose Sight of that Liberty in their old Age, which in their younger Years they had received pure and uncorrupted from Nature.” Some have called these People Birgantes from the River Birgus, the Barrow about which they inhabited. (Ware & Harris 38)

While it is entirely possible that the Irish Brigantes were an offshoot of the British branch, the reign of Vespasian is much too late for their removal to Ireland. By that time, the southeast quarter of Ireland had been thoroughly conquered and colonized by the Lagin, from whom the province of Leinster in this part of the country takes its name. As O’Rahilly demonstrated at length, Ptolemy’s description of Ireland does not contain a single trace of the Lagin, proving that Ptolemy based his description on data collected in Ireland before the Laginian invasion. The Irish Brigantes probably migrated to Ireland around 500 BC, the approximate time of the Belgic or Ernean invasion. O’Rahilly surmises that the Laginian invasion took place in the third century BCE (O’Rahilly 116). As a working hypothesis, I posit 250 BCE.

The passage which Harris places within quotation marks above is taken from an even earlier reference to the Brigantes of Ireland in William Camden’s Britannia (Camden 842), which was originally published in Latin in 1586. Elsewhere in this same work, Camden notes:

Brigantes, or Birgantes: The Brigantes seem to have been seated between the mouth of the river Swire [Suir], and the confluence of the Neor [Nore] and Barrow; which last is call’d by Ptolemy Brigus. And because there was an ancient City of the Brigantes in Spain, call’d Brigantia, Florianus del Campo takes a great deal of pains to derive these Brigantes from his own country of Spain. But, if conjectures are to be allow’d, others may as probably derive them from the Brigantes of Britain, a Nation both near and populous. However, if what I find in some Copies be true, that these People were call’d Birgantes, both he and others are plainly under a mistake: for then they take their name from the river Birgus [now Barrow,] about which they inhabit; as appears from the affinity of the names. These Brigantes (or Birgantes, which you please) peopled the Counties of Kilkenny, Ossery, and Caterlogh [Carlow], all, water’d by the river Birgus. (Camden 1351)

The pre-Goidelic Celtic identity of the Brigantes is not in doubt. Recently, however, the etymology of their name has been revisited. From Roman Era Names we have the following:

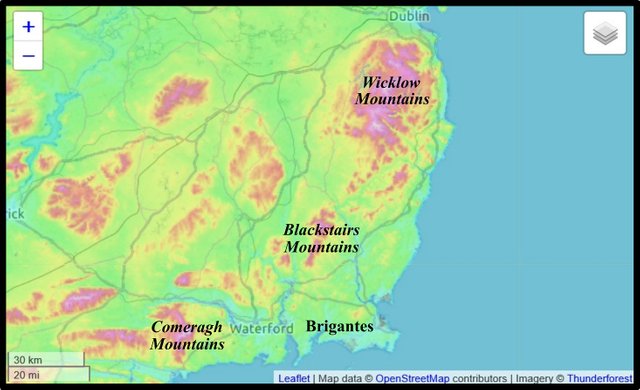

Βριγαντες (or Βριγαντας) (Brigantes 2,2,7 and 2,2,9) were ‘hill people’, presumably living in the Wicklow mountains, with a name that occurred across Europe in various forms. In Iberian early place names -briga is a marker for the zone of Indo-European speech. (Roman Era Names)

Unfortunately, this does not help us to pin down their territory in Ireland, as it is likely that they already bore this name when they colonized Ireland. Ptolemy’s description places them in the lowlands in the extreme south of County Wexford. If, however, we concede that they were originally hill dwellers, then I would be more inclined to locate them in the Blackstairs Mountains of County Wexford or the Comeragh Mountains of County Waterford.

The Brigantes are mentioned by a number of other Classical sources, though none of them refers to the Irish branch of this nation. Among the more notable, the following may be mentioned:

- Tacitus, The Annals 12:32

- Tacitus, The Histories 3:45

- Tacitus, Agricola 17

- Juvenal, The Satires 14:191

- Strabo, Geography 4:6:8

References

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Goddard Orpen: © Royal Society of Antiquaries Ireland, Fair Use

- William Camden: Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (artist), National Portrait Gallery, NPG 528, Public Domain

- Territory of the Brigantes: Map Data © OpenStreetMap, Imagery © Thunderfest, Fair Use

thank you for giving us always good posts.