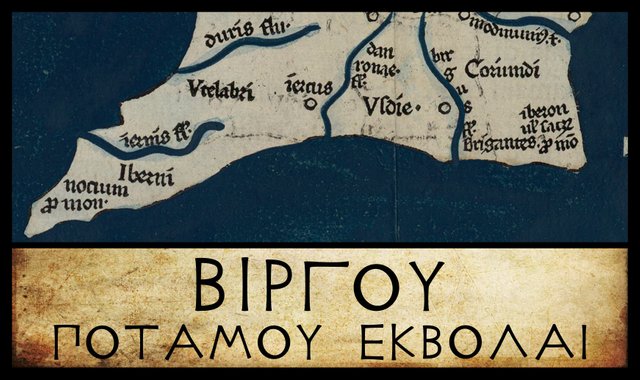

Βιργου Ποταμου Εκβολαι

We have almost reached the end of our voyage around Ireland, with Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography as our sailing directions. The final landmark before we arrive back at the Sacred Promontory in the southeast of the island is Βιργου ποταμου εκβολαι [Birgou potamou ekbolai], or Mouth of the River Birgos. The three modern editors I am following place this feature in the same latitude (57° 30') and the same longitude (12° 30'). Friedrich Wilberg, however, records two variants, one in a Byzantine manuscript and one in an early printed edition, while Karl Müller notes a few variants in a handful of other sources. Curiously, Wilberg and Müller differ in their reading of M, the Editio Argentinensis:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | 12° 30' | 57° 30' |

| A | 12° 30' | 58° 30' |

| M? | 12° 30' | 58° 50' |

| X, Σ, Φ, Ψ, M, 4803, 4805 | 12° 30' | 57° 50' |

A is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, Grec 1401. Βιργου appears on Folium 18. The latitude clearly has Η (eta), for the 8 in 58°, and this is followed by the symbol used for half a degree, giving us 58° 30'. Wilberg, however, only notes the 58°.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which we have met several times before. It was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name Argentorate. Müller’s reading of 57° 50' seems to be correct. Wilberg records 58° 50'.

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

4803 and 4805 are two of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. They are Latin translations of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803 and Latin 4805.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, one of the oldest surviving manuscript copies of Ptolemy’s Geography. It is now housed in the Vatican Library. The River Birgos is on folium 139r, in the third line of text, in the top left-hand corner of the page. Clearly, this manuscript locates the mouth of the Birgos in longitude 12° 30' (ιβ Ϛ´) and latitude 57° 50' (νζ Ϛ´γ´). This is the same latitude as the following item, the Sacred Promontory.

One variant reading of this river name has been recorded. As usual, Ptolemy recorded the name in the genitive case, Βιργου [Birgou], implying the nominative Βιργος [Birgos]:

| Edition or Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | Βίργου | Birgou |

| B, E, Z, L | Βάργου | Bargou |

B and E are two of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1404 and Grec 1403 respectively.

Z is Vaticanus Palatinus Graecus 314, a Greek manuscript from the old Palatinate Library of Heidelberg, which is now part of the Vatican Library in Rome.

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

I will not repeat the discussion from the preceding article in this series about Marcian of Heraclea, a 4th-century geographer, who believed that Ptolemy’s Southern Promontory was the most southerly point in Ireland. Suffice it to say that, notwithstanding the fact that all three 19th-century editors of Ptolemy chose to ignore Marcian, I believe that there are good reasons to accept his modification of the shape of the southern coast of Ireland:

Identity

Ptolemy’s River Birgos is universally identified with the River Barrow, the longest of the Three Sisters of Ireland. The Barrow is, in fact, the second longest river in Ireland, so it would have been surprising if Ptolemy had omitted to record it. The Three Sisters—the Barrow, the Nore and the Suir—rise in the Slieve Bloom Mountains in Counties Laois and Tipperary. The Nore flows into the Barrow about 3 km upstream of New Ross, while the Barrow flows into the Suir a further 16 km downstream. The Suir then flows for a further 7 km, before discharging into the Celtic Sea through Waterford Harbour, opposite Hook Head.

The convergence of scholarly opinion is understandable, as the identity of the Birgos and the Barrow seems quite secure: not only are both river mouths in the same place—on the south coast of Ireland, a short distance to the west of the island’s southeast corner—but they have similar-sounding names. However, the identity of the names is the one area of contention among the scholars. Most of the early scholars simply assumed that Ptolemy’s Birgos was the Barrow, and did not bother to explore any possible links between the Ptolemaic name and the native Irish name (Berba, Bearbha). Recently, however, it has been suggested that any similarity between Birgos and Bearbha is purely coincidental and that from a linguistic and etymological point of view they are probably unrelated.

Roderic O’Flaherty, writing in the late 17th century, is one of the few scholars to explicitly link the two names, though even he was skeptical of the connection:

Birgus, or Brigus, is rather incongruously derived from Bearva, the Irish name of the River Barrow. (O’Flaherty 25)

In the 17th century, the British antiquary William Camden connected the name of the river with that of the Brigantes, a native tribe which Ptolemy locates in this part of the country. The Welsh scholar William Baxter concurred, as did the Irish antiquaries James Ware and Walter Harris. Goddard Orpen also explored a possible connection with the Celtic goddess Brigit. It is apparently on account of these supposed connections that the name of the river is sometimes given as Brigus, a form not attested in any of the manuscript sources. This is a subject to which I will return in due course.

As usual, Charles Trice Martin followed Baxter and Harris, listing both the Birgus and the Brigus in his lexicon, and identifying them with the Barrow River, Ireland.

In the modern era, T F O’Rahilly was quite adamant that the ancient and modern names of the river were not related:

Birgos would correspond geographically to the Barrow (Ir. Bearbha, < *Berviā); but the two names must be unconnected unless we assume an extraordinary corruption in Ptolemy’s text. [Footnote: Pokorny, ZCP xiv, 334, compares Ir. bearg, ‘stream’ (known only from _bearg .i. sruth [bearg, i.e. stream], Ériu xiii, 66.1), which may be related to bir, ‘water’ (Meyer, Contrr. 218).] (O’Rahilly 4)

The Bohemian linguist Julius Pokorny, whom O’Rahilly cites in the footnote, did at least entertain the possibility that Ptolemy’s name was a corruption of the original word from which the modern Irish name derives:

The Barrow, Old Irish Berbae < Indo-European *bhervjā from the root bhereu “to move restlessly”, is usually identified with Ptolemy’s Birgos. Since in phonology, e and i are often interchanged, and also in old manuscripts Γ [Gamma] can be confused with Ϝ [Digamma], ΒΙΡΓΟΣ [BIRGOS] could stand for ΒΙΡϜΟΣ [BIRVOS]. However, there is another possibility. (Pokorny 334)

He then goes on to outline the etymology which O’Rahilly noted above, concluding that “Ptolemy thus transmitted the Pre-Celtic name of the river, to which the Celts later gave a new name”. I, of course, do not believe there ever was a Pre-Celtic name, as there were no Pre-Celtic people in Ireland.

The etymologists at Roman Era Names suggest a different Indo-European origin for Ptolemy’s Birgos, but they agree with O’Rahilly that the Irish name of the river is probably not related:

Βιργου river mouth (Birgu 2,2,6) was the river Barrow at Waterford Harbour. Βιργου would make excellent sense derived from PIE *bhergh- ‘to hide, to protect’, a root related to (or confused with) another PIE *bhergh- ‘high, hill’, which led to the English word barrow. There is an interesting parallel in Birgu, the historic capital of Malta, inside Grand Harbour, and also in Pergamon from Greek πυργος ‘tower’, but no Irish relative appears to be widely cited. (Roman Era Names)

Is it possible that Ptolemy’s text is the correct form and the early Irish Berba a later corruption?

It should be remembered that the Barrow flows into the River Suir a few kilometres downstream from Waterford City. From here to the sea, the combined river is called the Suir, not the Barrow. In other words, the mouth of the Barrow lies several kilometres inland, so the name of Ptolemy’s coastal river mouth is probably not related to the Irish name for the Barrow after all.

There is not much more to add. In my research, I did not come across a single scholar who identified Ptolemy’s Birgos with any river other than the Barrow. This is possibly the only one of Ptolemy’s Irish toponyms on which there is absolute unanimity.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Seán Duffy, Atlas of Irish History, Second Edition, Gill & MacMillan, Dublin (2000)

- Louis Francis (editor, translator), Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- Marcian, Karl Müller (editor), Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Kuno Meyer, Contributions to Irish Lexicography, Volume 1, Part 1, A-C, Max Niemeyer, Halle an der Saale (1906)

- Emmanuel Miller, _Périple de Marcien d’Héraclée, Epitome d’Artémidore, Isidore de Charax, etc., ou, Supplément aux Dernières Éditions des Petits Géographes : D’après un Manuscrit Grec de la Bibliothèque Royale _, L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris (1839)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland, G Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- A I Pearson, A Medieval Glossary, Ériu, Volume 13, pp 61-83, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1942)

- Julius Pokorny, Die Namen des Barrow [The Names of the Barrow], Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie, Volume 14, Max Niemeyer, Halle an der Saale (1923)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, Ptolemy’s Celtic Italy and Ireland: A Linguistic Analysis, in David N Parsons & Patrick P Sims-Williams (editors) Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe, University of Wales, CMCS Publications, Aberystwyth (2000)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Martin Waldseemüller’s Map of Ireland and Britain: Woodcut, Martin Waldseemüller (artist), Claudius Ptolemy, Geography (Editio Argentinensis, 1513), Public Domain

- The River Barrow (County Carlow): © Artur Kozioł, Creative Commons License

- The River Suir (Passage East): © Paul O’Farrell, Creative Commons License

- Woodstown Beach on Waterford Harbour: © tony quilty, Creative Commons License

Love your post dear

Posted using Partiko iOS