Help Wanted: Disaster Managers & Vector Ecologists to Save Our Museums and Libraries

Image by Emily Szalay from The Western Museums Association.

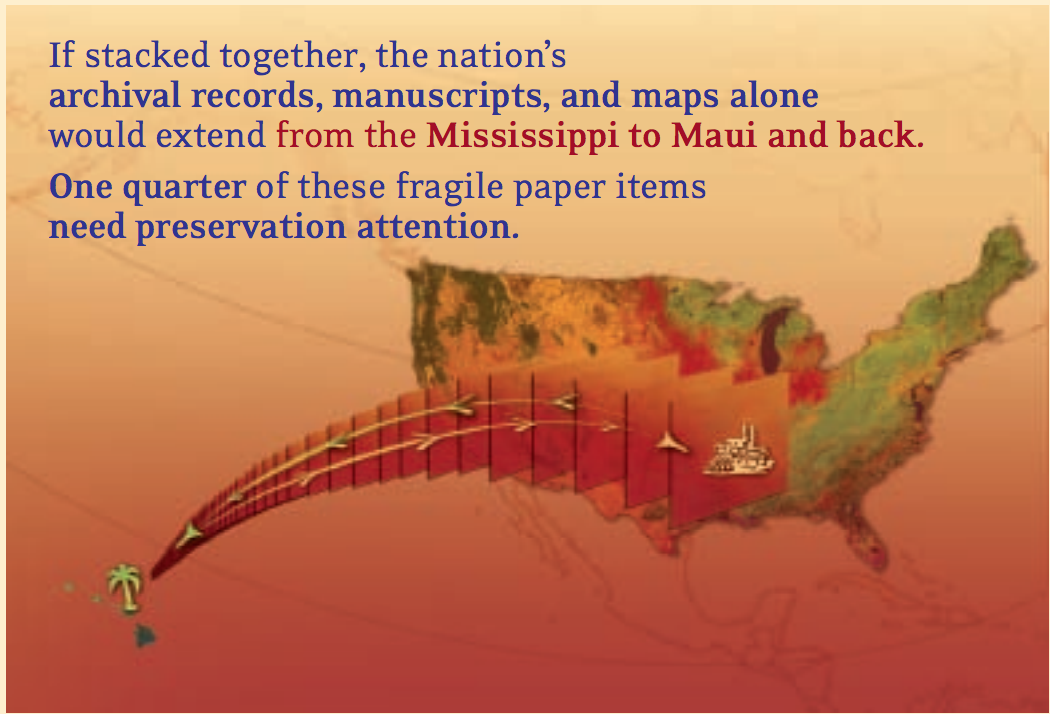

Did you know that the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works conducted an audit of all of the United States' cultural artifacts. Produced in 2005, The Heritage Health Index found that the most urgent preservation need at U.S. collecting institutions is environmental control.

Image from The Heritage Health Index.

It's not funding, it's not bigger audiences. Mother Nature and our negligence are the biggest threats to our cultural institutions. UV light, mold, pests, and environmental disasters- these are the true enemies of the cultured (pun intended) state.

Isn't it odd that culture conservationists and environmental conservations don't work together to help reach their shared goals? Why are museums/libraries not courting sponsorship and in-kind contributions from exterminator companies or one of many mold remediation businesses?

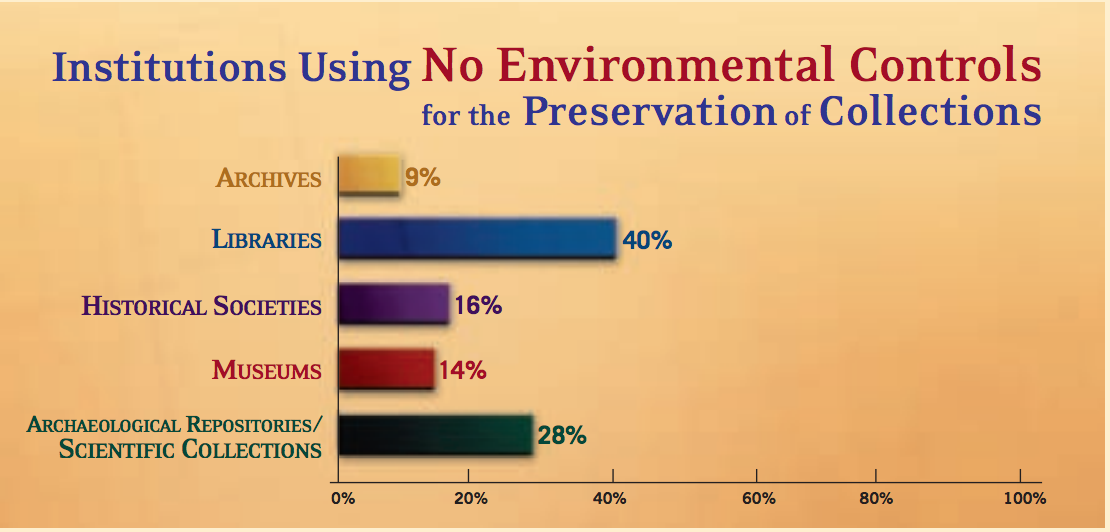

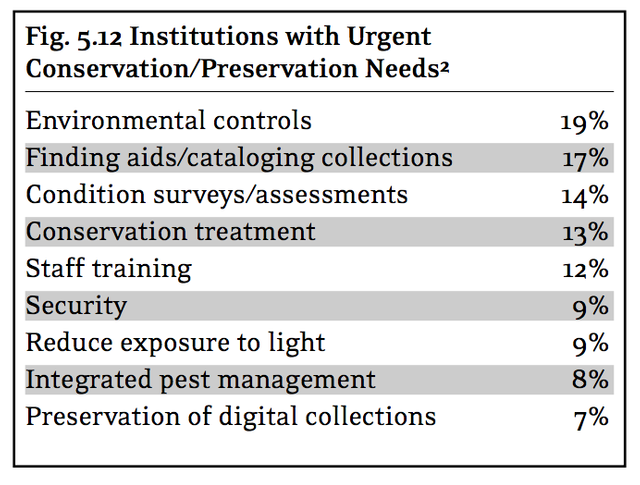

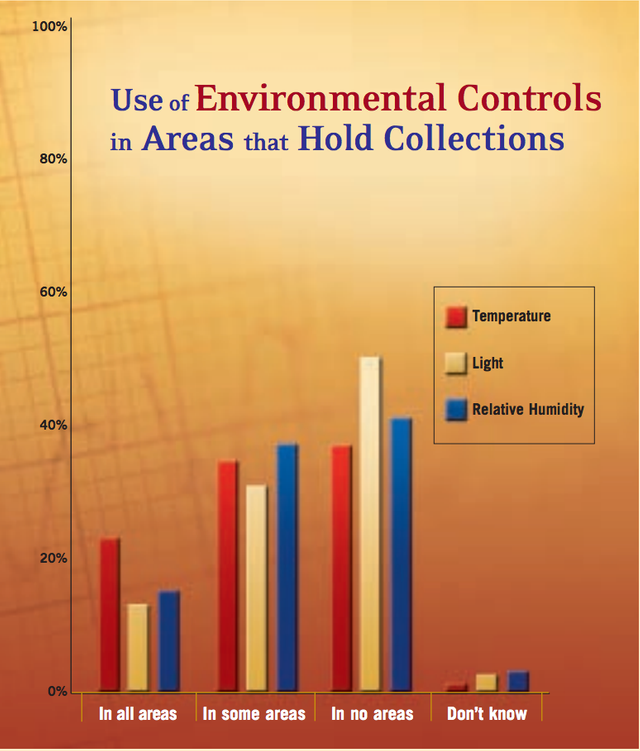

Rather than getting caught up in fads and making augmented reality exhibitions, maybe museums and collections should invest in the creation of an Integrated Pest Management plan. Check out these grim bar graphs:

Image from The Heritage Health Index.

Image from The Heritage Health Index.

Call me crazy, but this misalignment with reality and funding priorities in the cultural conservation sector is bonkers. It's like a 4 star restaurant having sub-par freezers and walk-ins. Why would you jeopardize one of the primary assets of your organization through neglect? This massive blindspot within our cultural institutions is a bigger threat than slashed NEA funding or deaccessioning art from the pubic trust. If the silverfish and book lice eat up all our primary sources how will we buttress our research?

*Urgent Need defined as major improvement required to prevent damage or deterioration to collections. ** (And we see how IPMs are slightly less urgent than digital collections. Accessibility and sustainability are clearly not funding priorities.)

Why bother doing the work of public history and conservation if the artifacts that we bestow such import on are frivolously guarded? We need more institutions like the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library and the University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation to spearhead meaningful action on this topic. In March 2017 they hosted a IPM training workshop to begin addressing this grave issue:

The workshop introduced participants to multiple aspects of IPM: policy and procedure; preventing infestation; trapping and monitoring; remedial treatment; basic pest identification. It was designed for small to mid-sized institutions needing to establish or improve an IPM program as well as anyone needing to develop or refresh basic IPM knowledge.

Rachael Perkins Arenstein, a conservator specializing in preventive care, Pat Kelley, an entomologist with extensive knowledge of museum collection care practices, and Matt Mickletz, the person responsible for the daily implementation of Winterthur’s IPM program, worked together to teach the theory and practice of IPM using a a combination of lectures, discussions and hands-on exercises. The workshop was coordinated by Professor Joelle Wickens, Associate Conservator and Preventive Team Head with funding generously provided by [Tru-Vue](https://tru-vue.com/).

The fact that this workshop was aimed at organizations "needing to establish or improve an IPM program," proves the necessity of this type of education and information sharing.

What good are lavish monumental buildings and state of the art libraries if we can't care for their occupants? Disaster management plans are not just public health artifacts but vital to the sustainability and impact of the public trust. Maybe this seems like a no-brainer to me since my bestie from college is a Board certified entomologist and I have understood for years that artsy nerds and science nerds make great friends. But we need to take action, fast. Before the next disaster strikes. Break down those silos and old preconceptions and start getting all the conservations under one tent.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

Yes! There's something seemingly insidious going on here. Remember we spoke about Baumol's cost disease (aka the Baumol effect) in relation to the increasing costs in the public history field a while back? I think this is one of the central causes that maybe deserves its own name.

Conditions were probably not much different fifty years ago, but the profession didn't then have the expertise to see it and the sector didn't make a priority of assessing the situation. And, of course, it's only been exacerbated by diversifying and proliferating collection priorities to reflect the recent idea of what should be collected and protected. Kind of like the Sorcerers' Apprentice scene in Fantasia.

Is this really a condition all it's own? If so, what to call it? The Fantasia Factor? The Apprentice Effect? Or maybe Scorcerer's Syndrome?

And more to the point: what should be done about it?

Interesting post. I also think that it is interesting where we decide to store much of our art. Should we have museums in places more prone to natural disasters and conditions that are more challenging to maintain? What is the sense in putting art museums in areas that are frequent victims of natural disasters? Even places that have seemingly avoided disaster for the last century, like Los Angeles, have important art and the potential for massive fallout should earthquakes, fires, or tsunamis.