about how interrogation is used to gain confessions from innocent people

...even to the extent of creating false memories where you actually believe that you are guilty.

I'm sure you're all on the edge of your collective seats waiting for my next "Steemian of the Week" post :-D

It's going to be awesome, but I won't be finished with it till tonight or in the am.

In the mean time...

I've been slowly reading Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary way to Influence and Persuade by Robert Cialdini(1) while waiting for the books I really want to read to come in at the library. A moment ago I came across an interesting section and want to share some of it with you all.

The whole book is about persuasion and influence. Specifically as an introduction to the subject Cialdini covers many of the ways influence is used against us. The 4th chapter is about how the focus of our attention determines what we think is important, and there's all kinds of research he cites to corroborate that belief. I don't have time here to go into all that, this is simply for background so you know where we are coming from.

I'm reading about how interrogation has been used to gain confessions, and how certain interrogation techniques can get you to falsely testify against yourself. Even to the extent of creating false memories where you actually believe that you are guilty. So we get to this part where Cialdini talks about Arthur Miller (Death of a Salesman) being brought before the US House Un-American Activities Committee and labeled as a communist, "blacklisted, fined, and denied a passport for failing to answer all the chairman's questions."

Miller was a speaker on a panel considering the causes and consequences of wrongfully obtained confessions along with Peter Reilly. Reilly was the victim of an interrogation where he was caused to admit guilt to the brutal rape and murder of his mother, and then later was proven innocent.(2)

Ok, there's the back-story, and now we can jump into the text and I'll type out a few paragraphs that I wanted to share with 'yall.

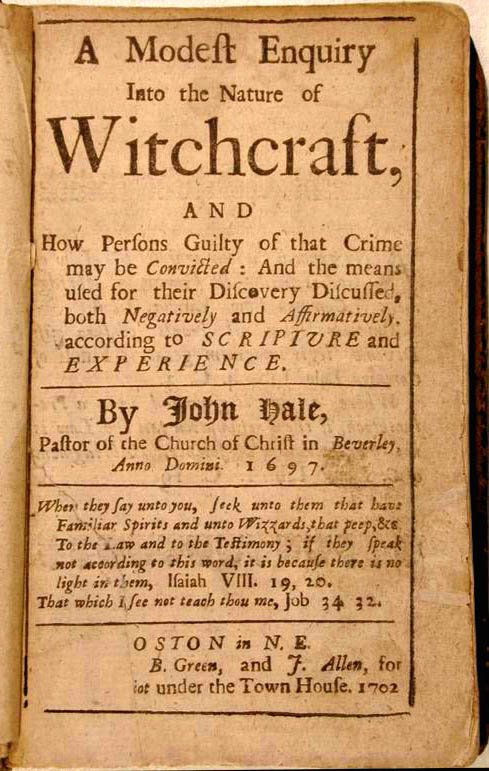

The role of confessions in Miller's plays can be seen in The Crucible, the most frequently produced of all his works. Although set in 1692 during the Salem witchcraft trials, Miller wrote it allegorically to reflect the form of loaded questioning he witnessed in congressional hearings at that he later recognized in the Peter Riley case.

Miller's comments on the panel with Reilly were relatively brief. But they included an account of a meeting he had in New York with a Chinese woman named Nien Cheng. During Communist China's Cultural Revolution of the 1960's and 1970's, which was intended to purge the country of all capitalistic elements, she was subjected to harsh interrogations designed to get her to confess to being an anti-Communist and a spy. With tear-rimmed eyes, Nien related to the playwright her deep feelings upon seeing, after her eventual release from prison, a production of The Crucible in her native country. At the time, she was sure that parts of the dialogue had been rewritten by its Chinese director to connect with national audiences, because the questions asked of the accused in the play "were exactly the same as the questions I had been asked by the Cultural Revolutionaries." No American, she thought, could have known these precise wordings, phrasings, and sequencings.

She was shocked to hear Miller reply that He had taken the questions from the record of the 1692 Salem witchcraft trials--and that they were the same as were deployed within the House Un-American Activites Committee hearings. Later, it was the uncanny match to those in the Reilly interrogation that prompted Miller to get involved in Peter's Defense.

A scary implication arises from Miller's story. Certain remarkably similar and effective practices have been developed over many years that enable investigators, in all manner of places and for all manner of purposes, to wring statements of guilt from suspects--sometimes innocent ones. This recognition led Miller and legal commentators to recommend that all interrogations involving major crimes be videotaped. That way, these commentators have argued, people who see the recordings--prosecutors, jury members, judges-- can assess for themselves whether the confession was gained improperly. And, indeed, video recording of interrogation sessions has been increasingly adopted around the globe for this reason. It's a good idea in theory, but there's a problem with it in practice: the point of view of the video camera is almost always behind the interrogator and onto the face of the suspect.

The rest of the chapter shows how what we are focused on can be a great influence on what our brains believe is important. Which all goes together with the point that since the camera is focused directly at the interviewee we are more likely to believe them guilty.

Very interesting stuff. I'm glad I picked it back up.

I'll be interested to see the comments on this one, and hope someone else picks up this book so we can chat about it.

Thanks for stopping by!

www.influenceatwork.com

This is Robert Cialdini's website where you can see more about who he is, what he does, and find his books.

@originalworks

@OriginalWorks Mention Bot activated by @inquiringtimes. The @OriginalWorks bot has determined this post by @inquiringtimes to be original material and upvoted it!

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @OriginalWorks in your message!

For more information, Click Here!

this was a test to see how the bot would respond to a post which is mostly a large quotation...

well, half half.

there's about equal text to quote.

Way to read the old posts! :)

It's one of the shortcomings of this platform.

Old posts can well be good posts

I can't make it work on my post at the moment. I thought it might have been as I didn't use the capital letters, but now I notice that you did it in little letters too