Medieval Japan: Bushido code, society, Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa epoch, also often referred to as the Edo period, lasted more than two and a half centuries, from 1600 to 1868. By defeating his rivals in the Battle of Sekigahara (1600), the outstanding military leader, thinker and legislator Ieyasu Tokugawa in 1603 officially received from the hands of the emperor the rank of shōgun, the Supreme military dictator and the actual ruler of the medieval Japan. After a hundred years of bloody internecine wars, known as the "Age of warring states" (Sengoku period), began a long period of peace and state construction, accompanied by an unprecedented flourishing of culture.

The political structure of Japan, united under the auspices of the Tokugawa shoguns, was called bakuhan and was based on two foundations - the supreme power of the Shogun government (bakufu) and the local feudal clans, headed by individual princes (daymōs) - medieval Japan was divided into states with local governors, just like USA. However, if formerly the daimyo-governors were almost independent in their feuds, now under the new regime they all became subordinates of the shogun- they swore allegiance and ruled in their "states" under his mandate. In case of a serious fault, daimyō could be deprived of all his privileges and his clan- disbanded.

The title of daimyo could claim the feudal lords with an income of at least 10,000 koku of rice (back then, all calculations were made in the "rice equivalent"). The largest clans had incomes of several hundred thousand koku and more, up to a half million - while the country's gross national income averaged about 30 million koku, and personally shogun's share accounted for 4 million koku.

Ieyasu Tokugawa set several categories of vassals. To the first category - hereditary daimyo (fudai) - belonged the heirs of the noblest vassal families; To the second category (simpans) - those daimyos that belong to the branches of the Tokugawa family; To the third category (tozama) belonged those allies who joined Ieyasu in the Battle of Sekigahara. And finally, the fourth category included those in personal service of shogun - hatamoto (banner men). To the first three categories belonged about 270 daimyos. The highest government posts could be occupied mainly by fudai and hatamoto.

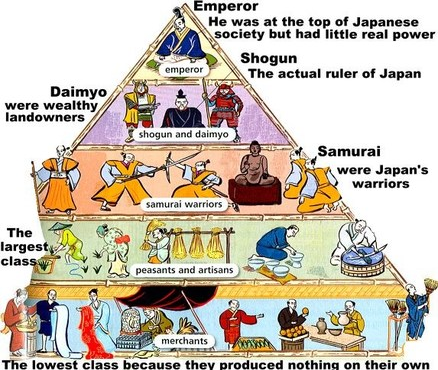

The Emperor, who was blessing the power of the shogun, was in fact isolated with his court from the world and country ruling (he had a symbolic status, like the British queen today).

The shogun had the right to make an individual decision on all issues of the state's foreign and domestic policies, and on all serious questions the daimyo had to address the shogun. In order to exclude the slightest possibility of discontent, to prevent disloyalty and treason in the state, Ieyasu introduced the sankin-kotai system, which obliged all princes to have, in addition to their own castles, a permanent residence in Edo, where the daimyo performed various duties at the shogun's court according to their rank and position, living there alone or together with the family, usually one year out of every two. The following year it was allowed to return to their native lands, leaving as a hostage any of the children or close relatives. For the sake of maintaining prestige in Edo farmsteads, the castle was furnished with luxury and decorated by professional designers, hundreds of samurai and servants constantly were stationed there.

The shogun granted the daimyo a certain independence in the management of their estates, but in return demanded the unconditional submission and compliance with state laws. The law of inheritance, relations between suzerain and vassals, rules of behavior in everyday life were strictly regulated. The slightest disobedience was strictly punished. The death penalty was a common for both ordinary samurais and powerful princes. However, as a rule, samurai - with the exception of malicious criminals - was allowed to part with his life by suicide. The verdict usually meant simply "seppuku", that is, hara-kiri. If the hara-kiri was done without haste, with appropriate ceremonies, an assistant-kaisyaku usually took part in it, who, for humanitarian reasons, chopped off the head of the unfortunate person immediately after he had stabbed the short sword in his stomach. In the case of seppuku, the family and relatives of the sentenced person were usually exempted from punishment.

A special role belonged to the head of the security department (ometsuke), who was responsible for the security and inner intelligence of the state. In cities and villages, there was established an exemplary system of open police supervision, supplemented by an effective system of secret investigation and surveillance. A popular measure for maintaining order was the introduction of collective responsibility within five-yard districts in the villages, and partly in the cities. The surveillance networks were spread so broadly that any conspiracy attempt was stopped at the very beginning. In addition, the creation of any groups with dubious goals was classified by law as "a criminal conspiracy," for which the punishment was the death.

The peace and order, that were guaranteed by the draconian laws, was called the Great Peace, which the Tokugawa government considered to be its sacred duty to maintain. To ensure that no external influences distract citizens from fulfilling their duties and strict observance of laws, it was decided to close the country and forcefully expel all foreigners, who for several decades successfully spread Christianity in Japan and propagated Western values. By a decree of the shogun of 1612, Christianity was prohibited. The final and irrevocable prohibition, accompanied with cruel persecutions of Christians, followed in 1637. Until the 1860s, Japan remained virtually a closed country, and minimal contacts with the West were maintained only through the Dutch trading post in Nagasaki (that very same town ...).

The shogunate legally established the existence of four classes: samurai, peasants, artisans and traders.

This division was borrowed from the old Chinese prescriptions, but in reality the "third class" was mixed- the townspeople preferred not to distinguish artisans and merchants, especially since many artisans kept their own shops, although there was also a category of wealthy merchant. The transition from the lower class to the higher, samurai, was practically impossible in the Edo period, although earlier in history such cases were not uncommon. The dominant class was samurai, which occupied an incomparably higher position on the social ladder than peasants and townspeople. Samurais attributed to a particular clan or directly to the shogun and carry a military, and sometimes civilian service, receiving a salary from his suzerain. The difference between classes was maintained in style and colors of clothes, in models of complex hairstyles, in education and upbringing, in language and customs. The main privilege of the samurai was wearing two swords - large and small. Along with the martial arts, the samurai were instructed to study philosophy, literature and some fine arts.

In case the samurai for any reason lost the suzerain or was fired from the service, he was losing his salary and turned into a ronin, a homeless vagrant, which was the greatest misfortune for professional soldiers, especially in peacetime. Ronin had a chance to find a new master, but this required recommendations from influential people. Those who could not find a permanent service, there were not many possibilities: either to wander around the country, settle down somewhere in the city and teach martial arts, calligraphy, declassify and go into the merchant class or become a mercenary- ninja.

The ideological support of the Tokugawa regime was Confucianism, adapted to Japanese reality.

Since Confucianism, in its core, is a doctrine of virtue, Tokugawa authorities from the very beginning adhered to the rather straightforward principle of "promoting good and punishing vice". In order to improve morals, "cheerful (gay) neighborhoods" were allocated to special "reservations", separated from the main areas of the city. Samurais were forbidden to visit the such places (of course most of them didn’t stick to the rule). Gambling was also forbidden. Attempts were made to prohibit the Kabuki theater, but the matter ended with the expulsion from Kabuki of actresses who served as a source of temptation for the well-to-do public, and their places were took by men or young men- wakashu – dressed in women’s clothes.

This measure, incidentally, led to the extraordinary spread of sodomy and homosexuality. Severe censorship tried to stop all manifestations of frivolity in literature, which, in turn, caused an unprecedented boom in erotic art. Although virtuous samurais in theory were assigned the role of guardians of morality, in reality they didn’t manage very well.

This measure, incidentally, led to the extraordinary spread of sodomy and homosexuality. Severe censorship tried to stop all manifestations of frivolity in literature, which, in turn, caused an unprecedented boom in erotic art. Although virtuous samurais in theory were assigned the role of guardians of morality, in reality they didn’t manage very well.

Confucian principles of vassal loyalty became the cornerstones in the formation of the samurai code of honor- the Bushido, the Way of the Samurai. The Tokugawa regime gave tis moral teaching the status of the law, and the code of samurai honor was elevated to the cult.

Bushido existed in Japan as an unwritten tradition. Instructions designed to educate courage and nobility in the soldiers were passed on in samurai families from generation to generation, gradually becoming the norm of everyday life. In the samurai environment, there were norms of upbringing and education that developed a certain cultural code that remained almost unchanged for many centuries.

A true samurai is characterized by all the basic Confucian virtues: a sense of duty, humanity, sincerity and unswerving obedience to the ritual. A true samurai is unpretentious in food, clothes and habitation, pure in thought, strict in his temper. He respects the elders, helps the younger, takes care of the parents, improves in the martial arts, learns sciences.

However, above all else stood the duty of serving the Lord, from whom the samurai received a salary, that is, a means of existence for his family. For the sake of service to the master the true samurai should be ready without hesitation to sacrifice own life and a life of the relatives. Medieval Japanese literature is full of examples of self-sacrifice in the name of saving the life and honor of the master, killing one's own child instead of the suzerain's son. The whole life of a true samurai was considered only as an instrument of service to the master. If the debt of Service could have been fulfilled at the cost of living, doubts and hesitations had to be discarded. At the same time, of course, the orders of the master were beyond discussion: any cruel and unjust order, be it murder or suicide, was to be carried out immediately.

In all life situations, the samurai had to follow the unwritten rules of Bushido. In fact, he had no alternative. To neglect the duty of honor meant to doom yourself to universal contempt, to shame - that was considered much worse than death. That is why in the trials of the Edo period followed not only the letter of the law, but also the prescriptions of the Samurai Way were always taken into account, and some cases could come into conflict with each other.

The Bushido code and the samurai image was extremely important for creating the ideological base of the renewed Japanese statehood. In the late 70's - early 80s of the XIX century, the government carried out an intensified propaganda against the samurai class, which was officially "abolished" in 1885. Ordinary samurai lost all their former privileges, although the nobility (former daimyo and partly hatamoto) were granted westernized titles of dukes, earls and barons (that existed until the end of World War II). Samurais were forced to part with traditional clothing, hairstyles and two swords. Throughout the country, a campaign was launched to destroy medieval castles as "the legacy of the accursed feudal past." However, very soon it became clear to the authorities that the elimination of Bushido's ideology along with the class privileges would lead to a spiritual vacuum and capitulation towards the Christian culture of the West.

Ideals of the samurais ways were first of all transferred to the Japanese army and navy, formed by Western models. However, after the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, during the period of American occupation, Bushido's ideology was officially banned as the core doctrine of Japanese nationalism and militarism. Bushido propaganda was banned in any form: in the press, in the theater, in the cinema and in the schools of traditional martial arts (which were also closed). The ban lasted from 1945 to 1949, after which it was lifted.

Some of my other posts:

Ahnenerbe? https://steemit.com/history/@vladimirk800i/ahnenerbe

Why we secretly like to draw penises https://steemit.com/videogames/@vladimirk800i/why-people-like-to-draw-penises

Pre-Internet memes https://steemit.com/history/@vladimirk800i/pre-internet-memes

What is Cargo cult? https://steemit.com/life/@vladimirk800i/cargo-cult

The Victorian Era alarm-clocks https://steemit.com/life/@vladimirk800i/the-victorian-era-alarm-clocks