Homo explorans – Voyagers Who Would Link the World

image source

What drove people in the fifteenth century to look to expanding from their known boundaries into the unknown? Three countries sponsored major explorations – Spain, Portugal and England – each with different priorities. Several leading factors which helped towards the general motivation by Western countries like Spain and Portugal to want to voyage, explore and discover new lands, new trading routes and new sources of wealth. One was the outbreak of hostilities between the Ottoman and Byzantine empires and the Muslim push into parts of India, which meant great difficulties in trading for the Iberians. Crusading had not been successful either, from a Western point of view, and the Holy Land was still under the control of Islam. While scientifically knowledgeable empires such as the Arabs and the Chinese had great skill on the water and knowledge of sea navigation, neither of them had the crusading Christian zeal for spreading their religious beliefs to the far corners of the globe. Also during the fifteenth century Guttenberg’s printing press came into being, which meant that maps could be reproduced.1 It became ‘de-professionalised’ as greater access to knowledge became widespread. In England, there was a desire to ‘rediscover’ land which had been found but then lost by earlier explorers, which could mean colonisation of new territories for them. Motives varied between Spain, Portugal and England, but there were really four main drives behind the undertakings – economics, crusading spirit, religious zeal (although the last two could arguably be classed as being very similar), and colonial expansion.

image source

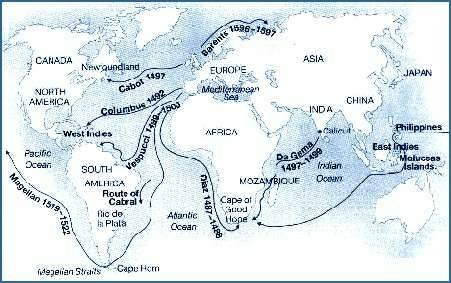

In the words of the historian J.C. Beaglehole: “In every great discoverer there is a dual passion – the passion to see, the passion to report; and in the greatest this duality is fused into one – a passion to see and to report truly.”2 Spain had Christopher Columbus, England had John Cabot, and Portugal had Bartolomeu Dias, Pêro da Covilhã, Vasco da Gama and Prince Henry. Although the Prince did not actually undertake the voyages himself, he was a great collector and collator of shipping knowledge. For Prince Henry – the Navigator – there was a great need for more revenue. Portugal needed grain, trade, gold and manpower. The Black Death had killed off many people and manpower was low. Although he wasn’t an explorer, for years Henry had been collecting information on anything to do with shipping, coastal geography, tides and currents, navigation, and tradable commodities. Collectively, all but the tradable-commodities information were useful resources in creating a science of navigation - ‘Portugal’s great gift to Europe’.3 Goods were brought to markets from across the desert by caravans of camels laden with cargo, but they took several months to arrive, demand was beginning to outstrip supply, it was a costly process, and with the outbreaks of war normal routes were being cut off. The Portuguese decided their best hope was for trading directly and collecting goods from the source, aided by an old rumour of a Christian king called Prester John and his empire, which they finally concluded must be in Ethiopia and Prester John the Emperor. If they found this empire they thought they could also gain an ally against Islam. Prince Henry was Portugal’s most knowledgeable choice for organising an expedition to discover the Christian empire and negotiate with Prester John for goods, services and political alliance.

the mysterious legend of Prester John started in the 12th century

image source

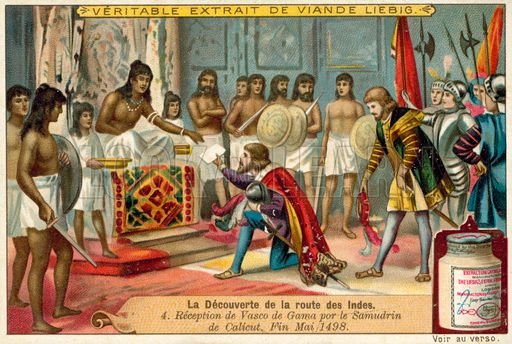

Prince Henry the Navigator (third son of the Portuguese King) was a Christian, and Governor of the Order of Christ, a chivalrous order – which meant he could appropriate funds from the Order for his exploration purposes. Thoughts of converting Muslims to Christianity was one probable motivation, another was to stop the spread of Islam into new countries. Crusade was one of the high motivators of European desire to voyage, which is why the Chinese, Arabs and other capable cultures did not pursue expansion. Islamic invasion of Byzantium cut off trade for Portugal. As part of his religious zeal, the Navigator was very happy when slaves were brought back from expeditions, because he saw the opportunity for “the salvation of those souls that before were lost”.4 Prince Henry sent out many secret expeditions for discovery of new lands, but none of them had the success of Pêro da Covilhã or Vasco da Gama. In 1487 Bartolomeu Dias was chosen to make the first attempt at trying to find a way to circumnavigate Africa in order to establish a direct trading route with India. He and his crew succeeded in going around the coast as far as Kwaaihoek before having to turn back as his crew, by then extremely weary and afraid, refused to carry on any further. Next, a chosen envoy of the King, Pêro da Covilhã did successfully sail around Africa and up the coast, finding in 1493 both Ethiopia and its legendary Emperor – Eskender (aka: Prester John); although unfortunately for him, any further exploration was curtailed by his being held in Ethiopia by the Emperor and his successors until his death several decades later. So, in 1497, after a ceremonial blessing, confession-hearing, and general absolution for future indiscretions, Vasco da Gama and a crew set sail with plenty of supplies, navigational knowledge, and the authority of a papal bull – secured by Prince Henry years before – for their journey. As da Gama’s ships sailed around Africa they would call in to ports and make purchases of goods such as ‘gold and slaves, red pepper, cotton, ivory, civets and palm oil’5 from coastal centres, sell at a good profit at other centres, thus gaining enough wealth to finance their next goal - a voyage to find India, which they successfully did. When da Gama met the ruler of Calicut in India, he diplomatically stated in his opening speech:

… for sixty years the ancestors of the present King of Portugal had sent out vessels of discovery to search for the way to India. They did this not from desire for silver or for gold, of which they had such abundance that they had no need of the wealth of other countries, but because they sincerely wished to become acquainted and to contract friendship with those of their fellow Christians who ruled in India…6

While in India de Gama struck trouble with the Muslims who had established trade with India and were fearful that trade would be usurped by the Portuguese, but eventually de Gama was able to sail home with ships full of riches and the certainty of a sea-based trading route for his country.

"Reception of Vasco da Gama by the Samudiri of Calicut, India, May 1498"

image source

Trade was not the motivation which drove Spanish support for a voyage, however. For Christopher Columbus, one motivation for organising an expedition was the possibility of discovery itself. It seems that:

from all the information he obtained, he came to believe without a doubt that to the west of the Canary Islands and the west of Cape Verde there was much land, and that it was possible to navigate thither and to make discoveries.7

Whether he was primarily intending to discover new lands across the ocean, or thought he could find a route across to India, Asia and the lands described by Marco Polo, is unclear. According to the historian João de Barros, Columbus thought that:

“by sailing farther west other islands and lands might be found, because it was unlikely that Nature had given the liquid element a preponderance over the terrestrial which was principally destined to receive life and see its development.”8

By the time Columbus had left Portugal and headed into Spain to find someone willing to support his proposed voyage he had an ‘enthusiastic belief in his divinely appointed mission to bring fresh souls to the knowledge of God and Holy Church’.9 This was the goal which eventually persuaded Queen Isabella of Spain to support Christopher Columbus in his venture. He and his crew set out in 1492 looking for the Far East, found America but failed to recognise the difference, and returned home in 1493. Compared to the Portuguese ventures, the Spanish one was extremely unsuccessful. Columbus later wrote to the King and Queen of Spain that he had been “induced to undertake his voyages to the Indies not by any information derived from human sources … but by a divine impulse”10 - which from the evidence was clearly not true, as he had been absorbing all the information from other sailors and documents he could find, before he applied for backing for his first voyage – and he believed that “the terrestrial Paradise would be found by him, and by him alone, in the southern regions of the Indies”.11 It was likely this very narrow-focused chivalric zeal which stopped Columbus from understanding just what he had discovered on his westward voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. Unfortunately for him, he also was not the first to reach the eastern coastline of America in the fifteenth century.

Christopher Columbus's journey

image source

John Cabot, Genoese by birth, sought support for his own expedition across the Atlantic Ocean, which he finally found in England from King Henry VII, who charged him with:

...free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea … to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.12

Ideas of finding suitable new lands for colonisation were also part of why England sponsored the expedition. Cabot sailed off from Bristol, England, later becoming the first documented European to explore North America, in 1497, in what experts agree must have been New Found Land – Newfoundland – or thereabouts. Certainly much further north than where Christopher Columbus went.13 Bartholomew Columbus, the brother of Christopher made his way to London seeking the sponsorship of England by King Henry VII for his brother’s proposed voyage. He was turned down, but the king heard all of Christopher’s theories and proposals, and this is most likely what began England thinking of their own voyaging plans, and so they put their faith not in the potential success of Columbus but in that of Cabot.

image source

The most likely reason for the English sponsorship’s stipulation that Cabot leave from Bristol was that they believed a Celtic legend that voyagers from Bristol had previously ‘found and discovered’ the ‘Ysle of Brasil’, but later lost it, and they were keen to find it again.14 Just when the explorers from Bristol discovered America that first time is still unclear as no direct evidence has yet been found. Nor yet any information on just why the explorers were on such a journey, although Bristol was a busy fishing port, so perhaps was initially linked to a search for more supplies of fish; or, if it was relegated to a Celtic legend then perhaps the voyage had happened much further back in time than they were guessing at. In any regard, finding new lands would be fortuitous for England in regards to colonial expansion; and if they happened to find a direct trade route to Asia by going west, even better.

enter link description here

While economics played a large part in what drove fifteenth century exploration for new lands and trade routes, it wasn’t the only major driving force. For Portugal it was, although halting the spread of Islam and converting people to Christianity ran a close second. For Spain, religious zeal rated highly along with desire for the discovery of new lands. For England, it was the ‘rediscovery’ of lands, with the hope of colonisation. In a sense, each motivation was weighed up with a sense of economic value – what would be the gain or reward from each venture, and whether the benefits would outweigh the investment. Regardless, though, those fifteenth century explorers were the men who were bold enough to link the world.

image source

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest.

References:

1 Roberts, J. M., and British Broadcasting Corporation. The Triumph of the West. 6, the Age of Exploration. [videorecording] 1 videocassette (50 min.). BBC Education & Training, London, 1987.

2 Fairchild, Wilma Belden. "Explorers: Men and Motives." Geographical Review 38 3 (1948): pp. 414. Print.

3 Jones, Vincent. Sail the Indian Sea. London New York: Gordon and Cremonesi, 1978. pp. 19. Print.

4 Newton, A. P. The Great Age of Discovery. Literature of Discovery, Exploration & Geography Series, 6. New York,: B. Franklin, 1970. pp. 47. Print.

5 Jones, Vincent. Sail the Indian Sea. London New York: Gordon and Cremonesi, 1978. pp. 34. Print.

6 ibid. pp. 83.

7 Newton, A. P. The Great Age of Discovery. Literature of Discovery, Exploration & Geography Series, 6. New York,: B. Franklin, 1970. pp. 80. Print.

8 ibid. pp. 84.

9 ibid. pp. 86.

10 ibid. pp. 21.

11 ibid. pp. 22.

12 "First Letters Patent Granted by Henry Vii to John Cabot, 5 March 1496". 2004. The Smugglers' City. Ed. Department of History, University of Bristol. 11 May 2011. http://www.bris.ac.uk/Depts/History/Maritime/Sources/1496cabotpatent.htm.

13 Quinn, David B. England and the Discovery of America, 1481-1620 : From the Bristol Voyages of the Fifteenth Century to the Pilgrim Settlement at Plymouth : The Exploration, Exploitation, and Trial-and-Error Colonization of North America by the English. 1st ed. New York,: Knopf, 1974. pp. 6. Print.

14 ibid. pp. 6.

You received a 60.0% upvote since you are a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "geopolis".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

Thank you so much, I really appreciate that you found it worthy. :)

This is a curation bot for TeamNZ. Please join our AUS/NZ community on Discord.

For any inquiries/issues about the bot please contact @cryptonik.

No Vikings? No Templars?

lol, while they would certainly have been noteworthy as explorers, they were beyond the scope of the essay question I was given at the time.

What was interesting to find out was that all the 'flat earth' assumptions were nonsense because one only had to look at the maps drawn by people of the time to see they did not believe the Earth was flat.

Just like Vikings never had horned helmets! :D

If you can tell a good story somebody else will repeat it and embellish it to make it better.

There were some good tellers before TV. Way back when the evening entertainment was a pint and a few stories at the Pub.

What a great look into the reasoning behind all of this historic exploration of "The New World". This post should serve as an example of what a history post could and should be here on SteemIt. So many turn into Wikipedia-like pages. This rises way above that. Great work!

This post was nominated by a @curie curator to be featured in an upcoming Author Showcase post on the @curie blog. If you agree to be featured in this way, please reply and:

randomwanderingsgene at gmail .com

You can check out our previous Author Showcase to get an idea of what we are doing with these posts.

Thanks for your time and for creating great content.

Gene (@curie curator)

Oh, thank you so much - both for your kind observations and for your offer.

I would love to be featured in the upcoming author showcase @randomwanderings, I'm sure it will be amongst very worthy talent!

You certainly have my permission to post excerpts. If I can think of anything brilliant to put into a blurb about myself or my writing, then I will indeed let you know. :)

Woah woah woah! No Magellan mention?? Haha! Still.. this was a great write up. I wonder if when they were exploring, they thought that their discoveries would not only change the world, but leave a lasting legacy for centuries. It was such an exciting time--the age of exploration--minus the Black Death and Spanish Flu.

I enjoyed reading your essay, as usual. You may have researched much of Europe's early sea travel of fourteen hundreds, but there is now evidence that the stories of Vikings visiting N. America are very likely true with townships found in Newfoundland. The Irish and Scottish Hebridian fisherman have many legends of having been washed up on western lands among the longshoremen men of an earlier time. The Welsh legend of a leather coracle being taken across to America and returning, is, or could be most pre-christian, and told by scribe monks to later Sanctify a Columban bishop of the pre-RC Celtic church. I personally would not wish to travel far in a coracle, but a lifeboat of canvas make has been known to travel thousands of miles in Atlantic conditions. In modern, relatively, times an armada of small boats crossed the narrows of the North Sea from East Anglia to Dunkirk and returned, many overladen. That sea was not as rough as the Atlantic might be, but other voyages have since been filmed, of two men rowing the Atlantic, or a small longship crossing the northern North sea. Take a gander at the size of the ship, in dock in the Thames, that took Sir Frances Drake to San Francisco Bay 60 yrs later, and was careened in Indonesia before coming home around Africa. Not something you would head out across an ocean in today!

They were pretty darned plucky, alright!

(I've just left a comment elsewhere here about how the Vikings etc were outside the scope of the essay I had to research for, but yes there would be some very interesting information to include otherwise.)

Nine green bottles standing on the wall, and if one green bottle should accidently fall, there'll be eight green bottles . . .

Research leads to leads to leads to . . .

My mates hated school, but I always loved it. Why¿ because it gave perimeters! Without a fence, one cannot be free 😂