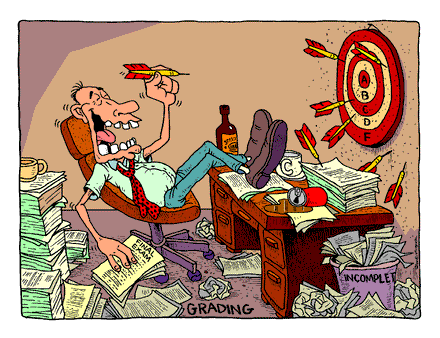

Grading for Math teachers - What's hot and what's not?

Myth:

A grade is an average of a series of scores on tests and quizzes. The accuracy of the grade is dependent primarily on the accuracy of the computational technique used to calculate the final numeric grade.

Reality:

A grade is a statistic that is used to communicate to others the achievement level that a student has attained in a particular area of study. The accuracy or validity of the grade is dependent on the information that is used in preparing the grade, the professional judgment of the teacher, and the alignment of the assessments with the true goal and objectives of the course.

For effective use of the assessment information gathered from problems, tasks, and other appropriate methods to assign grades, some hard decisions are inevitable. Some are philosophical, some require school or district agreements about grades, and all require us to examine what we value and the objectives we communicate to students and parents.

Confronting the Myth:

Most experienced teachers will tell you that they know a great deal about their students in terms of what the student know, how they perform in different situations, their attitudes and beliefs, and their various levels of skill attainment. Good teachers have always been engaged in ongoing performance assessment, albeit informal and usually with no recording. However, even good teachers have relied on test scores to determine grades, essentially forcing themselves to ignore a wealth of information that reflected a truer picture of their students.

The myth of grading by statistical number crunching is so firmly ingrained in schooling at all levels that you may find it hard to abandon. It should be quite possible to gather a wide variety of rich information about students' understanding, problem-solving processes, and attitudes and beliefs. To ignore all of this information in favor of a handful of numbers based on tests, tests that usually focus on low-level skills, is unfair to students, to parents, and to teachers.

One thing is undeniably true:

What gets graded is what gets valued.

When a grade of 75 percent or a C- is returned, all the student knows is that he or she did poorly. If, for example, a student's ability to justify her own answers and solutions has improved, should she be penalized in the averaging of numbers by a weaker performance early in he marking period?

Grading must be based on the performance tasks and other activities for which you signed rubric ratings; otherwise, students will soon realize that these are not important scores. At the same time, they need not be added or averaged in any numeric manner. The grade at the end of the marking period should reflect a holistic view of where the student is now relative to your goals and your value system. That value system should be clearly reflected in your framework for rating tasks.

What am I saying?

A multidimensional reporting system is a big help. If you can assign several grades for mathematics and not just one, your report to parents is more meaningful. Even if the school's report card does not permit multiple grades, you can devise a supplement indicating several ratings for different objectives. A place for comments is also helpful. This form can be shared with students periodically during a grading period and can easily accompany a report card. You can always involve students and parents in a discussion of a multidimensional approach to determining a grade based on rubric ratings for different components of your goals. Traditional test averaging has always done this. Not every test covers the same thing, and various scores (quizzed, homework, exams) are often assigned different weights. These are subjective, teacher-made decisions. The same subjective approach can be used with rubric scores without computing numeric averages.

Bibliography:

Elementary & Middle School Mathematics - Teaching Developmentally; 6th Edition; John A. Van de Walle; Pearson International Edition

Interesting. I'm not a manic mom and don't get my knickers in a knot about the marks my children get. I know there is more to life than marks and trust my judgement regarding my children's abilities. Living in a small, conservative South African town, this attitude does not win me conventional friends, especially in the school community. I value independent thinking above all else. I feel my children are penalised for this, but the way I see it that is also probably part of their "life" learning experience. Good teachers are worth their weight in gold, but are about as rare as gold.

They are very rare! Some parents are very worried about marks, teachers too. Children get used to this and feel undervalued when the marks doesn't show what the parents want it to show. It's sad. I'm also not worried about it and I think it can be less of a big deal.

It's very strange teachers are not vetted better, and paid more for skills, especially when they have the responsibility of moulding the next generation. A couple of the most evil people I have met have been teachers, but I have also seen teachers loving my kids as their own.

I've also had horrible ones but I prefer to remember the good ones. They made life in school less horrible, lol

In my experiences as a teacher i can give evidence to what you say. Its sad to see talented people undermined because they became nervious in a test.

It's true. You can be confident for an exam but because you are nervous it can have an affect on your grades.

Even as a teacher, I hope grades can disappear one day. It is way more important to see growth in students rather than their grades.

I don't think it will disappear soon, but if it could, it would be amazing!