The Genesis of Covid-19

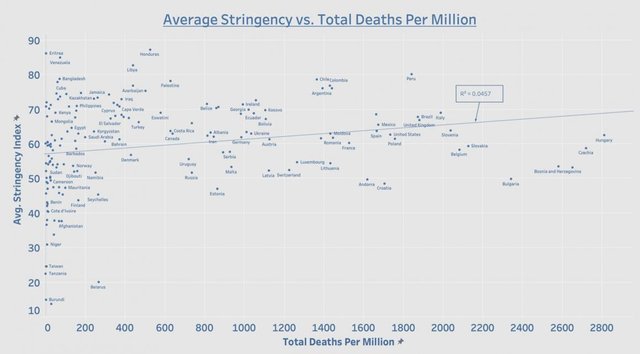

In the last article, we saw that there were very good reasons to suspect that whatever covid-19 might be, it is not a contagion. If it were, there should be a correlation between the stringency of the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) implemented to bring it under control and the numbers of covid-related cases, hospitalizations and deaths. But there is no such correlation.

When I published that article on my Hive blog, it received one comment, from a user called pfunk:

Drawing these conclusions from limited analysis of lockdown/mask effectiveness is a colossal logical leap. And I think those conclusions land very far from the truth.

I believe you are focusing too much on a few points of data and not considering other factors like social behavior and how it progressed since March 2020, and the timing of emerged variants (delta so far being the most virulent) being able to evade immune response even in people that have antibodies.

We now have about eighteen months’ worth of data on which to base our analysis, data from almost every country in the World. Limited is not the term I would use to characterize such an analysis. Comprehensive would surely come closer to the truth.

The second point made by pfunk—the ability of new variants to evade the immune response—is irrelevant. If the NPIs worked, these alleged variants would not be transmitted in the first place, and so would never be in a position to evade the immune response.

But if covid-19 is not a contagious disease, what is it? Where did this novel respiratory disease come from? What are its causes? That is what we will discuss in this and the next few articles.

The Genesis of Covid-19

What is now called COVID-19—coronavirus disease 2019—was first identified by doctors in the Chinese city of Wuhan:

In late December 2019, an outbreak of a mysterious pneumonia characterized by fever, dry cough, and fatigue, and occasional gastrointestinal symptoms happened in a seafood wholesale wet market, the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The initial outbreak was reported in the market in December 2019 and involved about 66% of the staff there. The market was shut down on January 1, 2020, after the announcement of an epidemiologic alert by the local health authority on December 31, 2019. (Yi-Chi Wu et al 217)

The use of the term mysterious to characterize this disease—repeated in many other accounts—suggests that there was something unusual about this type of pneumonia, something that distinguished it from “regular” pneumonia. But we are also told that the initial outbreak took place in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, a so-called “wet market” in Wuhan City, which lies about 680 km west of Shanghai, in the province of Hubei. This suggests that it was the sudden appearance of a cluster of cases at this market that first alerted the authorities that something unusual was taking place.

The clinical identification of this mysterious pneumonia as a novel coronavirus infection was made at Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, which is located about 6 km northeast of the market:

In December, 2019, a series of pneumonia cases of unknown cause emerged in Wuhan, Hubei, China, with clinical presentations greatly resembling viral pneumonia. Deep sequencing analysis from lower respiratory tract samples indicated a novel coronavirus, which was named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). (Huang et al 497)

In this account, there is nothing mysterious about the pneumonia. It greatly resembles regular viral pneumonia. But it is of unknown cause. Apparently, it is the sudden emergence of a cluster of cases in Wuhan that made this outbreak noteworthy:

Background A recent cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China, was caused by a novel betacoronavirus, the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). We report the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics and treatment and clinical outcomes of these patients. (Huang et al 497)

A few pertinent questions arise:

Did these initial cases display any unusual symptoms which would lead an epidemiologist to suspect that something out of the ordinary was taking place?

Was this cluster of cases of pneumonia in Wuhan unusual and worthy of further investigation?

Outbreak

The covid-19 pandemic began when 59 patients suspected of having been infected with a novel pathogen at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan were referred to the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital (formerly the Wuhan Medical Treatment Center), 6 km away:

The illness onset of the first laboratory-confirmed case of 2019-nCoV infection was on December 1, 2019 in Wuhan, China (Table 1).1 Initially, an outbreak involving a local market, the Huanan Seafood Market, with at least 41 people was reported. The local health authority issued an “epidemiologic alert” on December 31, 2019, and the market was shut down on January 1, 2020. A total of 59 suspected cases with fever and dry cough were referred to a designated hospital (the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital). Of the 59 suspected cases, 41 patients were confirmed by next-generation sequencing or real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). (Wu et al 218)

The 59 patients presented with fever, dry cough, fatigue, and occasional gastrointestinal symptoms. But these are common symptoms of pneumonia (NHS). Other symptoms that were reported (eg Wang et al 2) included “shortness of breath,” “dyspnea,” and “diarrhea,” which are all common symptoms of so-called viral pneumonia. So what was it about these 59 patients that made their cases unusual or triggered an epidemiologic alert? Apparently, it was simply the fact that they were all linked to the Huanan Seafood Market:

Following the pneumonia cases of unknown cause reported in Wuhan and considering the shared history of exposure to Huanan seafood market across the patients, an epidemiological alert was released by the local health authority on Dec 31, 2019, and the market was shut down on Jan 1, 2020. Meanwhile, 59 suspected cases with fever and dry cough were transferred to a designated hospital starting from Dec 31, 2019. An expert team of physicians, epidemiologists, virologists, and government officials was soon formed after the alert. (Huang et al 498)

So there was nothing particularly alarming about the pneumonia itself. It was the fact that a cluster of 59 cases arose in a short space of time in a small area of Wuhan that raised the alarm.

But this shared history of exposure to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was apparently a red herring. Huang et al explicitly make this the proximate cause of the epidemiologic alert, but Wu et al confirm that there was no shared exposure to the market:

A total of 59 suspected cases with fever and dry cough were referred to a designated hospital (the Jin Yin-tan Hospital). Of the 59 suspected cases, 41 patients were confirmed by next-generation sequencing or real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Twenty-seven (66%, 27/41) patients had history of Huanan Seafood Market exposure. However, there is a caveat that the first case on December 1 did not show history of Huanan Seafood Market exposure and the subsequent cases started on December 10, nine days later. (Wu et al 218)

One third of the 41 patients could not be linked to the market. And even “patient zero”—the index case— had no connection to Huanan.

Patient Zero

Today—October 2021—the origin of the pandemic is still shrouded in confusion:

The earliest date of symptoms for COVID-19, according to a study performed by Huang et al. (2020) and published in The Lancet journal, was December 1, 2019. However, there are other sources (Bryner, 2020; Davidson, 2020) claiming that individuals with similar symptoms may have presented themselves to hospital as early as November. According to the report, by South China Morning Post (Ma, 13 March 2020), the first person who presented similar cases was a male patient of 55-year old from the province of Hubei. However, Chinese doctors only came to realize that they were dealing with a new and serious virus [in] late December, when similar symptoms continued to increase every day, and mostly originating from Wuhan. According to the article in The Lancet, the first patient, and who they insist may be the first case, was reported on December 1, 2019, and who did not have direct link with the Wuhan Seafood Market that has been associated with the origin of the virus. This finding interestingly matches with Ma (2020) who also argues that the November 2019 case was not from Wuhan. The story as to the origin of the virus has fueled much political and social divides and is expected to evolve as further efforts are poured into understanding this crisis.

DAY 8—DECEMBER 8, 2019

The number of new patients voluntarily presenting themselves to hospital continued to increase (Bryner, 2020). Hospitals report new one to five cases with similar symptoms on average each day. However, this being a new virus, some sources quoted December 8 as the first day where the first patient in the city of Wuhan sought medical help for pneumonia-like symptoms ... information from Chinese authorities (Wuhan City Health Committee, 2020) and those of the WHO (WHO, 2020a) stated that December 8, 2019, marked the onset of the first 41 cases that were tested and which were later confirmed positive with COVID-19, then known as “2019-nCoV.” (Allam 2)

Far from clearing up the confusion, Zaheer Allam’s account of the genesis of the pandemic only raises more questions of its own. For example, he says that the earliest date of symptoms for COVID-19 ... was December 1, 2019, and that individuals with similar symptoms may have presented themselves to hospital as early as November. But, as we have already seen, the symptoms of covid-19 greatly resemble regular viral pneumonia. What distinguished these particular cases from regular cases of pneumonia?

Allam also states that Chinese doctors only came to realize that they were dealing with a new and serious virus [in] late December, when similar symptoms continued to increase every day, and mostly originating from Wuhan. Not only does this imply that the doctors could distinguish this form of pneumonia from regular pneumonia despite both having similar symptoms, but it also suggests that it was the outbreak of a cluster of cases in a small area of Wuhan that finally alerted them to the seriousness of the situation.

We will return to the question of clustering later. Allam admits that the initial outbreak was not confined to the Huanan Seafood Market and that the initial case did not even arise in Wuhan City. So, not only was patient zero not connected with the Huanan Seafood Market, he was probably not even the case of 1 December:

According to the government data seen by the Post [South China Morning Post], a 55 year-old from Hubei province could have been the first person to have contracted Covid-19 on November 17. From that date onwards, one to five new cases were reported each day. By December 15, the total number of infections stood at 27—the first double-digit daily rise was reported on December 17—and by December 20, the total number of confirmed cases had reached 60 ... By the final day of 2019, the number of confirmed cases had risen to 266, On the first day of 2020 it stood at 381. (Josephine Ma)

Despite these reports of patients presenting at hospital in November with the same common symptoms of pneumonia that were later identified as symptoms of COVID-19, the World Health Organization continues to see China’s wet markets as the likely source of the contagion. Even as late as April 2021, the WHO was still focusing its attention on Wuhan’s live-animal markets:

To further investigate possible direct zoonotic introduction, detailed trace-back studies of the supply chain of the Huanan market (and other markets in Wuhan) have provided some credible leads to be followed. (WHO 114)

So where does the truth lie?

Was there something mysterious about this type of pneumonia, something unprecedented which led epidemiologists to suspect that they were dealing with a novel disease?

Is the Huanan Seafood Market implicated in the outbreak, or was this a red herring all along?

Were the epidemiologic alert and the subsequent hunt for a novel pathogen triggered simply by an unusual number of cases of viral pneumonia in Hubei Province?

Clusters

That last question is worthy of further investigation. In her article in the South China Morning Post (30 March 2020), Josephine Wu reported that the number of cases of this new disease had reached 266 by 31 December 2019. But the concluding line of her article reads:

As late as January 11, Wuhan’s health authorities were still claiming there were just 41 confirmed cases. (Wu)

Did the authorities issue the epidemiologic alert on 31 December 2019 on account of 41 cases of viral pneumonia in Hubei, a province with a population of 58 million? Or was it a cluster of 266 cases that triggered the alert? Just how frequent is pneumonia in Hubei? A study in 2010 on the incidence and mortality of pneumonia in China between 1985 and 2008 had the following to say:

Pneumonia is one of the leading causes of death in adults and children in China. In urban areas, pneumonia is the fourth leading cause of death, and in rural areas pneumonia is the leading cause of death. A recent article in the Chinese literature estimated that each year in China there are 2.5 million patients with pneumonia and that 125,000 (5%) of these patients die of pneumonia-related illness. (Guan et al 1)

The population of China in 2010 was about 1.4 billion. These figures suggest that a province of 58 million people (Hubei) would be expected to have approximately 100,000 cases of pneumonia per annum—or 280 cases and 14 deaths every day. In Wuhan City, which has a population of about 11 million, about 50 cases of pneumonia are diagnosed every day, with 2-3 deaths. How, then, is a cluster of 266 cases in forty-five days (17 November - 31 December) alarming?

Clinical Definition

It seems that the authorities issued an epidemiologic alert and triggered the hunt for a novel pathogen for no apparent reason: there was not an alarming number of cases in a small area, and there were no unusual symptoms to excite curiosity. And so we are brought back to our original question: What was it about these 41 or 266 cases of viral pneumonia that led to it being considered “mysterious”?

Since the cause was unknown at the onset of these emerging infections, the diagnosis of pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan was based on clinical characteristics, chest imaging, and the ruling out of common bacterial and viral pathogens that cause pneumonia. Suspected patients were isolated using airborne precautions in the designated hospital, Jin Yin-tan Hospital (Wuhan, China), and fit-tested N95 masks and airborne precautions for aerosol-generating procedures were taken. This study was approved by the National Health Commission of China and Ethics Commission of Jin Yin-tan Hospital (KY-2020-01.01). Written informed consent was waived by the Ethics Commission of the designated hospital for emerging infectious diseases. (Huang et al 498)

Did the chest imaging reveal some unusual features? How were common bacterial and viral pathogens ruled out? Perhaps some answers are to be found in another article in the South China Morning Post, which appeared on 31 December 2019. This article actually defined what the authorities meant by _pneumonia of unknown cause” and also explained how bacterial pneumonia was ruled out:

State health authorities define “pneumonia of unknown cause” as cases where the patient suffers a fever higher than 38 degrees Celsius, has characteristics of pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome present in imaging findings, has a normal or lowering white blood cell level or a falling absolute lymphocyte count, with no improvement after three to five days of antibacterial treatment. (Mandy Zuo)

This is very similar to the clinical definition of COVID-19 that appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine in January 2020 (Li et al). Independent researcher David Crowe did not find this clinical definition particularly impressive:

Infectious diseases always have a definition, but they are usually not publicized too widely because then they would be open to ridicule. They usually have a “suspect case” category based on symptoms and exposure, and a “confirmed” category that adds some kind of testing.

Reference [13] [Qun Li et al] describes a suspect case definition for COVID-19, derived from WHO definitions for SARS and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome). This definition was in effect until January 18, 2020, and required all four of the following criteria:

“Fever, with or without recorded temperature”. Note that there is no universal definition of fever, so this may just be the opinion of a physician or nurse. With SARS a fever was defined as 38C even though normal body temperature is considered to be 37C (98.6F).

“Radiographic evidence of pneumonia”. This can occur without illness, as was seen in a 10 year old boy with no clinical symptoms [3]. He was diagnosed with pneumonia despite this.

“Low or normal white-cell count or low lymphocyte count”. This is not really a criterion as every healthy person is included. This is also strange because people suffering from an infection normally have elevated white blood cell counts (although they may drop in people dying from an infection).

One of the following three:

“No reduction in symptoms after antimicrobial treatment for 3 days”. This is a standard indication of a ‘viral’ pneumonia, i.e. one that does not resolve with antibiotics.

“Epidemiologic link to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market”. This, and the next criterion, create the illusion of an infectious disease, as it prefers the diagnosis of connected cases.

“Contact with other patients with similar symptoms”. (Crowe 7)

The article by Qun Li et al that Crowe cites leads us a little further down the rabbit hole. It actually gives us some more details about the initial discovery that something out of the ordinary was taking place in Hubei:

Since December 2019, an increasing number of cases of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)–infected pneumonia (NCIP) have been identified in Wuhan, a large city of 11 million people in central China. On December 29, 2019, the first 4 cases reported, all linked to the Huanan (Southern China) Seafood Wholesale Market, were identified by local hospitals using a surveillance mechanism for “pneumonia of unknown etiology” that was established in the wake of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak with the aim of allowing timely identification of novel pathogens such as 2019-nCoV. (Li et al 1200)

Now we are getting somewhere. This detail is not mentioned in any of the other sources cited above:

On December 29, 2019, the first 4 cases reported, all linked to the Huanan (Southern China) Seafood Wholesale Market, were identified by local hospitals using a surveillance mechanism for “pneumonia of unknown etiology” ...

The source cited for this tidbit of information is Xiang et al, Use of National Pneumonia Surveillance to Describe Influenza A(H7N9) Virus Epidemiology, China, 2004–2013, which appeared in the CDC’s monthly publication Emerging Infectious Diseases, in 2013:

Since 2004, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) has conducted surveillance for pneumonia of unknown etiology (PUE) to facilitate timely detection of novel respiratory pathogens, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and avian influenza ... From 2004 through March 2013, health care facilities of all types in China were required to report any patient who had no clear diagnosis and whose illness met 4 criteria. These criteria were 1) fever (axillary temperature >38°C); 2) radiologic characteristics consistent with pneumonia; 3) reduced or normal leukocyte count or low lymphocyte count during early stages of disease; and 4) worsening of symptoms or no obvious improvement after 3–5 days of standard antimicrobial treatment. (Xiang et al 1784-1785)

And there, presumably, we have the source for the clinical definition of covid-19. According to Li et al, four cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology, all connected with the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, were identified by the surveillance system PUE on 29 December 2019. Two days later, the epidemiologic alert was issued.

What was it about these four cases that set off the PUE alarm? The four criteria listed above could be met by any case of regular viral pneumonia, which accounts for almost 50% of all pneumonia cases (Wikipedia). With 2.5 million cases of pneumonia in China every year, the PUE alarm can hardly be expected to go off more than a million times. In fact, there were only 1,016 PUE cases in the nine years from 2004 to 2013 (Xiang et al 1787). And if viral pneumonia is assumed to be a contagious infection, a cluster of four cases associated with a seafood market in Wuhan should not raise any concern.

The Four Cases

In his account of the first fifty days of the pandemic, Zaheer Allam records the following for 29 December 2019 (Day 29), the day on which four cases of “pneumonia of unknown etiology” were identified by the PUE surveillance system, which in turn triggered the epidemiologic alert of 31 December:

As hospitals continued to receive more patients with unknown “pneumonia-like symptoms,” fear of the outbreak is already spreading, especially among the social media (WeChat) use within China, more so Wuhan (Secon, 2020). Li et al. (2020) explained that during the period beginning December 1, 2019, the recurrence of the words “SARS” and “shortness of breath” in the social media started to increase, and by December 29, it had peaked. Meanwhile, in the hospitals, doctors were observed to concede that there might be a new virus of unknown etymology [sic, recte “etiology”] in Wuhan, presenting symptoms of acute respiratory syndrome. The reporting is affirmed by availability of the first four cases officially confirmed. All the four cases were linked to the Huanan (Southern China) Seafood Wholesale Market, which has been highly linked to have been the source of the virus. While only four cases had been pointed, by this date, Bryner (2020) reports that already, over 180 people in Wuhan had been infected, but since doctors had not earmarked them as suspected cases noting that there were no suspicion of this “unknown” disease. The 180 cases were only identified after doctors cross-verified records. The suspicion after reporting the four cases was that they were not suffering from SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which was still in surveillance since it broke in 2003. With the possibility of an unknown outbreak, at this time, the concern was to establish the transmissibility, severity, and other issues that may be related to this new virus (Adhikari et al., 2020). (Allam 2)

Obviously, English is not Allam’s first language, but the overall picture is clear. There were only four official cases that triggered the alert: namely, the four cases identified by the PUE surveillance system. Any earlier cases of covid-19 were only subsequently confirmed, so they were irrelevant to the issuing of the epidemiologic alert.

Allam, in common with other researchers, does his best to convey the impression that unofficially there was growing fear in the Wuhan area that an outbreak of a SARS-like epidemic was underway. But he never explains what it was that caused this growing fear. The symptoms being reported were not unusual for viral pneumonia and the numbers of cases were not unusual for a highly populated province like Hubei or a highly populated city like Wuhan. If doctors were concerned by cases of a SARS-like pneumonia prior to 29 December, why were these cases not reported to the authorities through the PUE surveillance system? The fact that no cases before 29 December were identified by PUE implies that none of the cases before 29 December was unusual. Why, then, was there a growing fear of an outbreak?

Allam’s allusion to alarmist chatter on social media, particularly in the Wuhan area, is suspicious. Who was the source of this chatter? Were doctors in Wuhan genuinely concerned that another SARS-like epidemic was underway, or were agents provocateurs deliberately spreading disinformation online—laying the groundwork, as it were, for a subsequent pandemic? Why would a doctor spread fear of an epidemic on social media but fail to alert PUE of the growing number of patients with unknown “pneumonia-like symptoms”? This all sounds very fishy to me.

Online Chatter

Allam’s source for the alarmist chatter on Chinese social media prior to the epidemiologic alert is an article by Holly Secon on the African media site Pulselive Kenya. Secon’s source, however, is a Chinese paper with the poorly translated title WeChat, a Chinese social media, may early detect the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in 2019. An improved translation of this paper was published online by JMIR in October 2020. The authors of the paper claim that the terms such as “Feidian”—Chinese for SARS, or “severe acute respiratory syndrome”—were trending on WeChat since 15 December, sixteen days before the first four official cases of the pandemic:

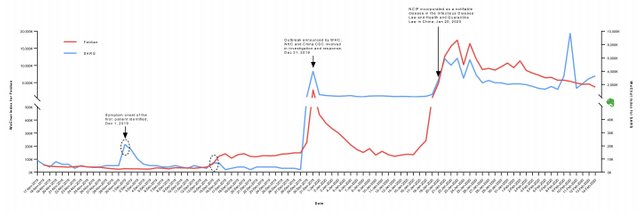

Methods: WeChat Index is a data service that shows how frequently a specific keyword appears in posts, subscriptions, and search over the last 90 days on WeChat, the most popular Chinese social media app. We plotted daily WeChat Index results for keywords related to SARS-CoV-2 from November 17, 2019, to February 14, 2020.

Results: WeChat Index hits for “Feidian” (which means severe acute respiratory syndrome in Chinese) stayed at low levels until 16 days ahead of the local authority’s outbreak announcement on December 31, 2019, when the index increased significantly. The WeChat Index values persisted at relatively high levels from December 15 to 29, 2019, and rose rapidly on December 30, 2019, the day before the announcement. The WeChat Index hits also spiked for the keywords “SARS,” “coronavirus,” “novel coronavirus,” “shortness of breath,” “dyspnea,” and “diarrhea,” but these terms were not as meaningful for the early detection of the outbreak as the term “Feidian”.

Conclusions: By using retrospective infoveillance data from the WeChat Index, the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in December 2019 could have been detected about two weeks before the outbreak announcement. WeChat may offer a new approach for the early detection of disease outbreaks. (Wang et al 1)

The authors suggest that the occurrence of several cases of viral pneumonia in a single region is enough to make health care providers think of SARS:

If the clinical manifestations and chest images indicate viral pneumonia and several similar cases occur in a region in a short period, health care providers may think of SARS (“Feidian” in Chinese). When suspected cases are admitted to hospitals, the involved physicians may mention “Feidian” and communicate on WeChat using this word. (Wang et al 3)

Once again, the authors fail to explain what made these cases of viral pneumonia so different from the 40,000 or so cases of regular viral pneumonia diagnosed in Hubei Province every year. Nor do they explain why the number of cases should be alarming, given that approximately 100-150 cases of viral pneumonia are diagnosed in Hubei every day. And finally, they do not explain why none of these health care providers alerted PUE. In fact, PUE is never even mentioned in this paper:

Traditional surveillance systems typically rely on clinical, virological, and microbiological data submitted by physicians and laboratories. Due to time and resource constraints, a lack of operational knowledge of reporting systems, and regulations associated with these systems, substantial lags between an outbreak event and its report are common. (Wang et al 1-2)

But PUE is not a traditional surveillance system. It is an alert system that was put in place as recently as 2003 for one very specific reason: the early detection of another SARS-like outbreak. If the official narrative is correct, COVID-19 is exactly what PUE was put in place to detect. It makes no sense to say that health care providers were concerned enough to spread fear and alarm on social media but never bothered to alert PUE. And this in authoritarian, totalitarian China, where failure to fulfil your legal requirements or “civic duty” could have very serious consequences!

The question has to be asked: Were these online messages about a possible SARS-like outbreak taking place in Wuhan seeded by government shills as part of a coordinated plan to prepare the public for a pandemic? If they were innocent “tweets” from genuinely concerned health care providers, what was it about these cases that so alarmed them, and why did they not report them through the official channels?

The WeChat data indicate a sudden spike in references to SARS on 1 December 2019:

The WeChat Index results for “SARS” were stable, except for the first three days in December, with a peak on December 1, 2019. (Wang et al 2)

What caused this spike? According to the authors, a single case of pneumonia was responsible:

The frequency of the term “SARS” in WeChat was unusually high from December 1 to 3, 2019, compared to the days before and after. According to Huang et al, the symptom onset date of the first patient identified was December 1, 2019. (Wang et al 4)

But as we have seen, Huang et al reported that the symptoms displayed by these initial cases were classic symptoms of viral pneumonia:

In December, 2019, a series of pneumonia cases of unknown cause emerged in Wuhan, Hubei, China, with clinical presentations greatly resembling viral pneumonia. (Huang et al 497)

And if the patient of 1 December was suffering from severe acute respiratory syndrome, why was his case not reported to PUE?

We have also seen that the patient of 1 December may not have been patient zero:

However, there are other sources (Bryner, 2020; Davidson, 2020) claiming that individuals with similar symptoms may have presented themselves to hospital as early as November. (Allam 2)

Why did none of these earlier cases cause SARS to start trending on WeChat? And why were none of them reported to PUE?

Questions, questions, questions, but few answers.

Censorship

The next puzzle to unravel concerns allegations that the Chinese authorities silenced whistle-blowers who tried to alert them of a possible outbreak of a SARS-like illness in Hubei Province.

The PUE system of surveillance was put in place for the early detection of a SARS-like outbreak. But when the very thing it was on the look-out for arrived, doctors and health care providers did not use it. Instead they tried to alert their colleagues and superiors through back channels, such as social media and whistleblowing. And when the authorities were alerted to the possibility of an outbreak, they tried to censor the whistle-blowers.

One story in particular was widely reported by Chinese and international media outlets:

A doctor in Wuhan has spoken out after seeing several of her colleagues die from the coronavirus, criticising hospital authorities for suppressing early warnings of the outbreak in an interview censors have been trying to erase from the internet.

In an interview with the Chinese magazine, Renwu, or People, Ai Fen, director of the emergency at Wuhan Central hospital, said she was reprimanded after alerting her superiors and colleagues of a SARS-like virus seen in patients in December. (Davidson)

Ai Fen is at the centre of this media storm. She claims that she is not a whistle-blower, but the person who provided the whistle for the whistle-blowers. But there are a number of things about this story that do not add up:

On 30 December, after seeing several patients with flu-like symptoms and resistant to usual treatment methods, Ai received the lab results of one case, which contained the word: “Sars coronavirus.” Ai, reading the report several times, says she broke out into a cold sweat.

She circled the words Sars, took a photo and sent it to a former medical school classmate, now a doctor at another hospital in Wuhan. By that evening, the photo had spread throughout medical circles in Wuhan, where it was also shared by Li Wenliang, becoming the first piece of evidence of the outbreak.

That night Ai said she received a message from her hospital saying information about this mysterious disease should not be arbitrarily released in order to avoid causing panic. Two days later [1 January 2020], she told the magazine, she was summoned by the head of the hospital’s disciplinary inspection committee and reprimanded for “spreading rumours” and “harming stability”. (Davidson)

The problem with this story is that PUE had already been triggered by the four cases on 29 December, and the epidemiologic alert was issued on 31 December, one day before Ai was reprimanded.

Nowhere in his article does Davidson mention the PUE surveillance system. Nor does he explain why Ai Fen did not make use of it. Nor does he explain why the Chinese authorities would introduce such a system for the early detection of a SARS-like outbreak and then try to silence doctors who inform them of just such an outbreak. Or why they would try to silence a doctor after they themselves have already issued an epidemiologic alert.

The story of Ai Fen is another complication that only makes it harder to get to the bottom of the matter. I suspect it is another red herring.

Conclusions

The genesis of the covid-19 pandemic is still shrouded in mystery and confusion. The official narrative is that as early as 1 December 2019 many doctors and health care providers in Wuhan City suspected that an outbreak of a SARS-like disease was taking place. These fears increased on 15 December and were sustained until the issuing of an epidemiologic alert on 31 December. But none of these doctors referred any suspect cases to the PUE surveillance system. And none of the suspect cases presented with symptoms inconsistent with regular viral pneumonia.

It cannot be argued that the alarm was raised by the sudden emergence of a cluster of numerous cases of viral pneumonia—ie the occurrence of more cases in a small area than would normally occur. At no point in 2019 were the hospitals in Wuhan overwhelmed by a sudden outbreak of viral pneumonia. In fact, the covid-19 pandemic emerged from just a handful of cases:

The initial spike in the term SARS on WeChat was prompted by the symptom onset of a single case of viral pneumonia on 1 December 2019. None of the symptoms presented by this case were unusual for viral pneumonia.

The epidemiologic alert of 31 December 2019 was triggered when the PUE surveillance system picked up just four cases of viral pneumonia on 29 December.

Around 100 cases of viral pneumonia are diagnosed in Hubei Province every day, or about a dozen in Wuhan City every day.

The hospitals in Wuhan were not suddenly overwhelmed by a deluge of cases. In fact, nothing out of the ordinary seems to have been happening in the run up to the issuing of the epidemiologic alert.

These fears, which laid the groundwork for the subsequent pandemic, can only have been based on clinical diagnosis. Laboratory diagnosis, which is alleged to have identified a novel coronavirus as the pathogenic cause of these cases of PUE, was first carried out on 30 December on samples collected from patients at the Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital:

Three bronchoalveolar-lavage samples were collected from Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital on December 30, 2019. No specific pathogens (including HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1) were detected in clinical specimens from these patients by the RespiFinderSmart-22kit. RNA extracted from bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid from the patients was used as a template to clone and sequence a genome using a combination of Illumina sequencing and nanopore sequencing. More than 20,000 viral reads from individual specimens were obtained, and most contigs matched to the genome from lineage B of the genus betacoronavirus—showing more than 85% identity with a bat SARS-like CoV (bat-SL-CoVZC45, MG772933.1) genome published previously. Positive results were also obtained with use of a real-time RT-PCR assay for RNA targeting to a consensus RdRp region of pan β-CoV (although the cycle threshold value was higher than 34 for detected samples). Virus isolation from the clinical specimens was performed with human airway epithelial cells and Vero E6 and Huh-7 cell lines. The isolated virus was named 2019-nCoV. (Zhu 730)

But Ai Fen works at Wuhan Central Hospital, 4.5 km SSW of Jinyintan Hospital. If the first identification of a novel coronavirus as the alleged pathogen was made at Jinyintan Hospital on 30 December, how did Ai Fen receive a laboratory test result with the words “Sars coronavirus” on the same day?

And finally, the association of these early cases of PUE with Wuhan’s Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market appears to have been a red herring. Many of the early cases suspected of suffering from covid-19 had no link with the wet market, and it has never been confirmed whether or not bats were being sold at this particular market.

This is all very suspicious. Nothing out of the ordinary appears to have been happening in China at the end of 2019, but within a few months the World Health Organization was declaring a pandemic and the whole World was going into lockdown. How did the Chinese convince the rest of the World that something very unusual was happening in Hubei Province? That is what we will look at in the next article.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Zaheer Allam, Surveying the Covid-19 Pandemic and Its Implications: Urban Health, Data Technology and Political Economy, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2020)

- David Crowe, Flaws in Coronavirus Pandemic Theory, Version 8.5 (6 June 2020), The Infectious Myth, Published Online (2020)

- Xuhua Guan et al, Pneumonia Incidence and Mortality in Mainland China: Systematic Review of Chinese and English Literature, 1985–2008, PLOS ONE, Volume 5, Issue 7, e11721, San Francisco, CA (2010)

- Chaolin Huang, Yeming Wang, Xingwang Li, Lili Ren, Jianping Zhao, Yi Hu, et al, Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China, The Lancet, Volume 395, Issue 10223, Pages 497-506, Elsevier Ltd, London (2020)

- Qun Li et al, Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia, The New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 382, Number 13, Pages 1199-1207, Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, MA (2020)

- Josephine Ma, Coronavirus: China’s First Confirmed Covid-19 Case Traced Back to November 17, South China Morning Post, 13 March 2020 (2020)

- Anthony Rozmajzl, Why Is There No Correlation between Masks, Lockdowns, and Covid Suppression?, Mises Wire, 4 May 2021, Mises Institute, Online (2021)

- Holly Secon (2020), Chinese Social-Media Platform WeChat Saw Spikes in the Terms ‛SARS,’ ‛Coronavirus,’ and ‛Shortness of Breath,’ Weeks Before the First Cases Were Confirmed, a Study Suggests, (2020)

- Wenjie Tan, Xiang Zhao, Xuejun Ma, et al, Notes from the Field: A Novel Coronavirus Genome Identified in a Cluster of Pneumonia Cases—Wuhan, China 2019−2020, China CDC Weekly, Volume 1, Number 4, Beijing (2020)

- Wenjun Wang, et al, Using WeChat, a Chinese Social Media App, for Early Detection of the COVID-19 Outbreak in December 2019: Retrospective Study, JMIR mHealth and uHealth, Volume 8, Issue 10, e19589, JMIR Publications, Toronto (2020)

- WHO, WHO-Convened Global Study of the Origins of SARS-CoV-2, World Health Organization, Geneva (2021)

- Nijuan Xiang, Fiona Havers, Tao Chen, et al, Use of National Pneumonia Surveillance to Describe Influenza A(H7N9) Virus Epidemiology, China, 2004–2013, Emerging Infectious Diseases, Volume 19, Number 11, Pages 1784-1790, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (2013)

- Yu-Chi Wu, Ching-Sung Chen, Yu-Jiun Chan, The Outbreak of COVID-19: An Overview, Journal of the Chinese Medical Association, Volume 83, Issue 3, Pages 217-220, Taipei (2020)

- Na Zhu et al, _A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019 _, The New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 382, Number 8, Pages 727-733, Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, MA (2020)

- Mandy Zuo, Mystery ‘Pneumonia’ Hits China’s Wuhan City: 27 Hospitalised with 7 in Serious Condition, South China Morning Post, 31 December 2019 (2019)

Image Credits

- COVID-19 Poster: © 2021 Dublin Region Homeless Executive, Fair Use

- Average Stringency Index Versus Total Deaths per Million (World): © Anthony Rozmajzl, Fair Use

- Wuhan, Hubei Province, China: © Andrew Horne, Creative Commons License

- A Wet Market in Wuhan: © Arend Kuester (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital: © 2017 Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, Fair Use

- The Hunt for Patient Zero: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization: © Denis Balibouse (photographer), Reuters, Fair Use

- Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market: © Aly Song (photographer), Reuters, Fair Use

- Headquarters of the South China Morning Post: 22 Dai Fat Street, Hong Kong, © 2021 Google, Fair Use

- David R Crowe: © Estate of David Richard Crowe, Fair Use

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing: © China CDC, Fair Use

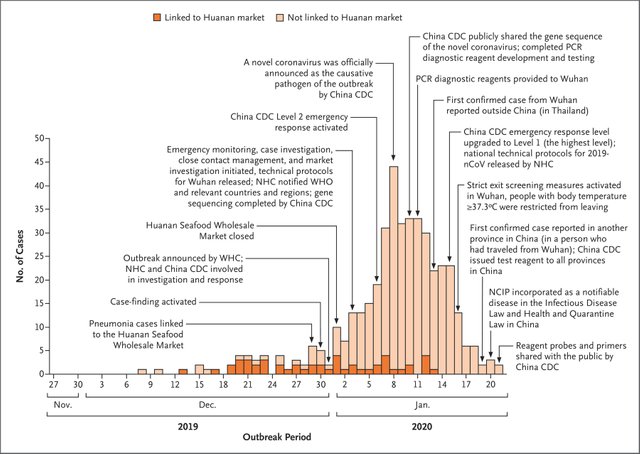

- The First 425 Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 (Li et al 1202): © 2020 Massachusetts Medical Society, Fair Use

- WeChat: Public Domain

- Flag of the People’s Republic of China: Public Domain

- Wuhan Central Hospital: Xu Keyue (photographer), © 2021 Global Times, Fair Use

Online Resources

- Covid Cribsheet

- Ireland: Study of Covid-19 Deaths

- RIP.ie

- Central Statistics Office (CSO)

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA)

- Covid-19 Pandemic

- Covid-19 Pandemic in the Republic of Ireland

- Covid-19 Pandemic in Northern Ireland

- Irish Government Updates on Covid-19

- Northern Ireland Covid-19 Statistics

- The CIA’s World Factbook

- EUROMOMO

- Our World in Data

- Rational Ground