Divided by Government – United on Principles

No matter your political identity, the desire for individual liberty is practically universal.

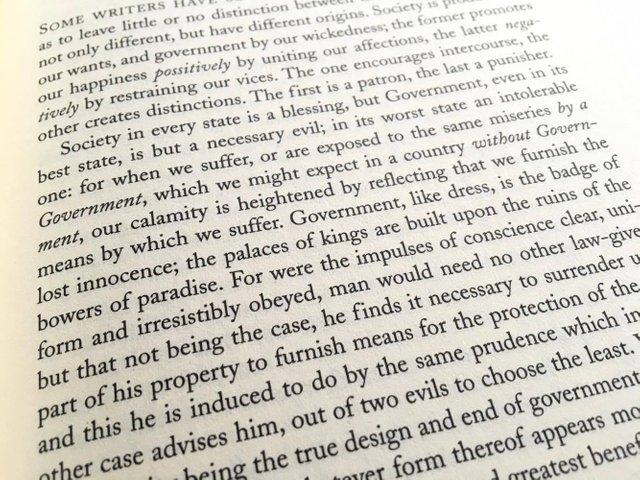

In the world of politics, regardless of the time or place, there always seems to be a unique conception of morality and rights. In the United States, these concepts are simultaneously asserted and rejected by different groups on both sides of the political aisle. The two main parties do not differ when it comes to accepting the assumed authority to create and enforce laws. The differences are only with the particular people or objects targeted by those laws.

Rarely – if ever – will you hear any arguments about whether or not the general authority is legitimate or justified in the first place, which is where any such discussion about law should begin. Instead, the divisions center on whether or not the state ought to be enforcing their laws on this or that specific person or property and these divisions are mostly split down the opposing party lines. Both sides are united on the principle that the state can justifiably create and enforce laws against the wishes of the governed under their claim of authority. However, both sides are also united on the notion that the state should not have control over certain aspects of an individual’s life or property.

The disagreement over the people or objects in question is simply a matter of political ideology, not philosophical principle or any coherent concept of rights. If the philosophy was logically sound, then the individuals could not concede that the state has the legitimate authority to make laws without the consent of those it governs and claim that the state does not have the authority to create laws that violate that consent. It can be readily observed that this is certainly not the case. Each side maintains a great deal of contradictions that they obviously don’t recognize or don’t care to correct.

Conflicting Political Positions

As an example of the divisions of politics, let’s look at a few specific topics where the two parties are generally divided on law and policy.

On one side of the aisle, it’s common to hear this type of argument:

“Making drugs illegal doesn’t mean that demand for them will suddenly not exist. Individuals will seek drugs in the black market at inflated costs from potentially dangerous people. Besides, I should be able to do what I want with my own body.”

These statements are correct and the underlying concepts involved are that of self-ownership and self-determination. Nobody’s rights are violated by one individual willingly trading with another willing individual. Furthermore, nobody’s rights are violated when an individual willingly consumes a substance. Volitional trade and consumption – in and of itself – does not harm any individual. There is no conflict and thus no need for a law governing interaction.

On the other side of the aisle, there is generally a similar argument:

“Making guns illegal doesn’t mean that demand for them will suddenly not exist. Individuals will seek guns in the black market at inflated costs from potentially dangerous people. Besides, I should be able to buy what I want with my own money.”

Again, these statements are correct – for exactly the same reasons as mentioned above. The act of willingly purchasing and owning a firearm is not a violation of anyone’s rights. Nobody is harmed during the volitional trade and the mere ownership of a gun.

These are only two examples, but looking at the opposing parties, there is a clear divide that is based on nothing more than a flawed concept of body and property – and how they can be interpreted as distinctly separate. One side typically argues, “I should be free to do what I want with my own body.” The other side says, “I should be free to buy or trade what I want with my own money and property.” These two concepts are rarely argued consistently, despite both of them being correct.

Misunderstanding Economics

With an incomplete understanding of economics and autonomy at the philosophical level, it’s very easy to hold contradictory beliefs or opinions. What may appear to be logically sound may actually be practically absurd. Likewise, what may appear to be a ridiculous concept could really be just an observation of what actually occurs within both nature and social constructs. The perception would simply depend on one’s comprehension of the subject matter.

Consider the attempt by some collectivist anarchists to differentiate “possessions” from “property.” It is argued that a possession – such as a hammer or sickle – may be rightly used in order to work as a self-employed individual. Acquiring that hammer and sickle by creating it with their own labor was a morally justified action. Any subsequent use of those tools by that individual for the purpose of earning a living is likewise morally justified. However, the same individual cannot rightly charge a fee to another person who wants to borrow the tools and use them for their own benefit. The actual owner of the possessions instantly becomes a profit-seeking exploiter of the underclasses.

This type of argument against different forms of possessions or property demonstrates a considerable amount of economic ignorance. The individual who created the hammer and sickle has every right to use those tools as his own possessions. The question is, why? If you ask the collectivists, they will likely mention something about labor and the absence of hierarchies or land rents. Conveniently, however, they will not address the fact that the possessor of those tools must have laid claim on some form of land in order to create them. A hammer and sickle are created from land resources, which – according to the collectivist anarchist – cannot be rightly owned by any individual.

The individual who made the unjust claim on the property in land is now using those resources in order to personally gain from them, to the exclusion of the rest of the community. Yet this is acceptable to the collectivist – because the origin of the possession is seemingly divorced from the use of it. A man using his own tools in order to feed his family is proper and admirable. Did he make the tools himself, and if so, with what resources? That has apparently not been considered, or it is entirely irrelevant.

A man that has no tools of his own – because he is not skilled enough to create them – must rely on the use of tools created by others. How does this man acquire them? If all of the possessions of other individuals are rightly theirs, because they are used by them in the course of their daily lives, then either a surplus of tools must be created or a rightful possessor must be willing to temporarily give up their use of those tools so that another may use them. The man without tools is asking the man with tools to either create them on his behalf or to suspend his work. If the latter man asks to be compensated for this, he is doing so unjustly and immediately becomes a bourgeoisie oppressor.

The concepts that are argued here conflict in a variety of ways. One individual can simultaneously own and not own the same “possession” or “property,” depending on how or when it is used. Another individual can justifiably claim a right to use land resources – which is a “property” claim – to the exclusion of others in order to create his own “possessions,” which are then used to earn a living and acquire additional “possessions.” A tool can be used for earning a living by one man and then be a tool for exploitation of another man only seconds later. The concepts of money and specialization are dismissed altogether while self-ownership and self-determination are completely lost in a jumbled mess of economic illiteracy.

Collectivists in general fundamentally argue for self-ownership in several instances, but then largely argue against the extension of the concept to property that would help to ensure and maintain self-ownership, self-preservation, and self-determination. Not surprisingly, their contradictions aren’t unique to them.

The Separation of Economic and Social Liberty

Observed in many of the debates and policies between the two major political parties in the United States is an attempt to divide the liberty of an individual into two separate parts: economic and social liberty. This is a typical position held by one side of the political aisle:

“The government has no right to tell me that I must purchase health insurance – and nobody should be permitted to produce, sell, purchase, possess, or use certain drugs.”

As mentioned previously, the entire notion of a government having the legitimate authority to make such laws in the first place is false. Regardless, there is an explicit contempt for any rational thought in this type of argument.

To admit that that a government has no right to compel any individual to spend their money on a specific good or service is no different than admitting that this government has no right to prevent any individual from spending their money on a specific good or service. The item for sale or consumption should not determine the buyer’s liberty to purchase or consume it. If you have the economic liberty to purchase a firearm or insurance, then you have the same liberty to purchase your drug of choice. Both are based on the same fundamental principles of self-ownership and self-determination.

Those who argue against these principles are attempting to separate social behavior from economic behavior. An attempt to compel or prevent purchases also compels individuals to associate with or prevents them from freely associating with other individuals. It becomes a forced structure of interpersonal relationships. This can be witnessed again from the following argument:

“No business owner should be permitted to refuse their goods or services to any customers – and everyone should be forced to buy health insurance.”

There is no difference whatsoever in compelling individuals to sell their goods or services to those with whom they do not want to associate and compelling individuals to purchase goods or services from them. In both cases, economic and social liberties are violated – just as they are when laws dictate firearm or drug purchases and possession (and use, in the latter case).

Arguing for laws that will deprive individuals of property, command specific use or prevent use of property, or command individuals to engage in certain economic behaviors is an explicit rejection of their social rights to voluntarily associate and trade with others – and it is a rejection of individual autonomy, or self-ownership. If you oppose specific social liberties, then you oppose economic liberty, and vice-versa.

The Golden Rule

As individuals, we essentially agree on the principles. Very few people – if any – want their lives to be controlled by others. The principles are necessarily recognized by us and applied in our private relationships but contradictorily applied in government and politics, mostly due to the lack of philosophical and economic understanding and consistency. The government is used as a means to control other individuals and their behaviors, despite the fact that private, coercive control of individuals is almost universally and fundamentally rejected.

If we apply to government our personal beliefs and behaviors that we have adopted among our friends, families, and business relationships, there would be virtually no calls for any laws beyond protecting our individual liberties of life and property from either unjustified violence or theft and fraud. Every time one side of the political aisle recognizes that a law is unjust and illegitimate because it violates their individual liberties, they ought to consider that there are similar laws equally violating the liberties of others, which they might support. Once that recognition occurs, there should be no further competition for capturing the authoritative offices of government that not only makes all of those violations possible, but expands and perpetuates them.

Treat others as you would like to be treated. It’s a simple concept. It’s what most of us naturally desire in our private lives (assuming that we believe we’re good people). There’s no need to circumvent those principles and desires in order to create a functional society. Believing that a government can perform this task by evading morality altogether – or worse, by dictating it – is an entirely counterintuitive assumption.

Governments divide us where there is ultimately no natural divide. It would be beneficial to stop looking to them for answers and start seeking non-contradictory principles for your own code of ethics. If we all made a legitimate attempt to do this, we’d be amazed at how much we really have in common with our neighbors and any desire for coercive control over them, minimal or not, would likely vanish. This is one of the fundamental aspects of any voluntary society. Without this understanding, violent coercive authority – which we reject in our individual lives – will continue as the predominant system of organization.

*(All images used herein originated with me.)

You've done it again. Nice job.

It really is amazing that so many people can't grasp the contradictions that they spew when it comes to laws and politics.

Great article and congratulations for the success!

Your use of a hammer and sickle as demonstrations of possessions as opposed to property. Very clever.

I'd also like to point out that your assertion is correct, and it is a universal, a priori fact: one cannot consent to have one's consent violated. We all want our consent respected. It is a phenomenal feat of absurdity that this conception disappears the larger the number of people in the given conversation.

I was going to use a saw as an example, as some other communist had done, but I thought the hammer and sickle would be better for the imagination. I wish I had a hammer and sickle to photograph. I'm a bit disappointed about that.

About consent -

I have an essay that I've been working on and should have it up soon, perhaps by next week.

All very well.

I even agree with most of it.

However I've recently come to the conclusion (based on life long experience and observation) that any group larger than about a hundred and fifty (Dunbar's number)

is insane.

Just as a stopped clock is right twice a day, insane organizations sometimes do things right.

But not often.

I have no idea how to fix the "problem" (it has to do with wetware ) but we need to keep it in mind.

It's an interesting problem, isn't it? We can recognize basic principles as individuals, but throw a large crowd of people together and they tend to collectively turn to madness.

Regarding governments, the proposed and enacted solutions have been to try to coerce people to "sanity" or morality (assuming that it's even necessary in the first place). Clearly, that hasn't worked well. We must find a better way - and it starts with understanding ourselves and our own desires when interacting with other people on an individual basis.

The founding fathers had a clue. They recommended small holdings, small governments and small business. The problem is size. Large is insane.

Nice post@ats-david! Check out my new post if you have a chance: https://steemit.com/sports/@acassity/week-1-nfl-season-predictions-who-will-win-september-8th-12th-predictions-by-acassity

Gracias Por compartir este material. Me gusta Lo que has Publicado Muchas Gracias