Thiomargarita namibiensis: Meet The World's Largest Bacteria

Ever wondered how big the world's largest bacteria gets to be? Well, I did today and after 10 seconds of googling I discovered it's Thiomargarita namibiensis which on average is 0.1–0.3 mm in diameter, but sometimes can reach a diameter of 0.75 mm. To give you a perspective, the average diameter of spherical bacteria is 0.0005 - 0.002 mm ( 0.5-2.0 µm) while for rod-shaped bacteria the average length is 0.0001 - 0.001 mm (1-10 µm) and the average diameter 0.00025 - 0.001 mm (0.25-1 .0 µm).

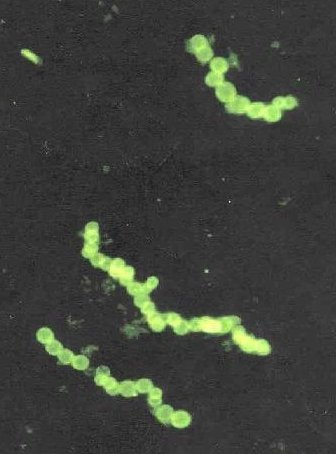

Stained microphotograph of Thiomargarita namibiensis bacteria (public domain)

And to give you an even better perspective, if T. namibiensis was a blue whale, then the average bacterial cell would be slightly smaller than a new-born mouse. T. namibiensis is actually big enough to be visible with the naked eye, almost as big as the periods of this post!

The species was first discovered by a group of German, Spanish, and American researchers sampling sediment off the coast of Namibia and was officially described in 1999.

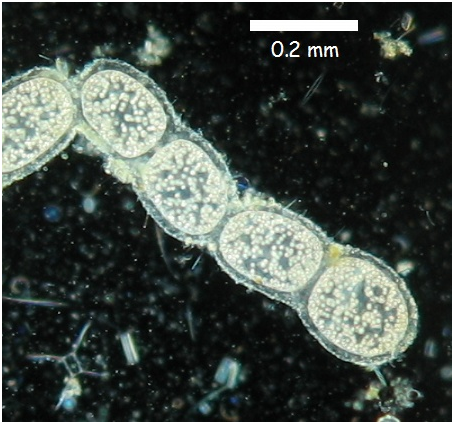

Image illustrating morphology of Thiomargarita namibiensis. (credit)

The bacterium's name means "Sulfur Pearl of Namibia", from the greek word θείο meaning "sulphur", the Latin word "margarita" for pearl and.. namibiensis for Namibia. All this, a direct reference to the location where the bacterium was first found and the fact that it uses sulfates for energy:

The bacterium is chemolithotrophic and is capable of using nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor in the electron transport chain. The organism will oxidize hydrogen sulfide (H2S) into elemental sulfur (S). This is deposited as granules in its periplasm and is highly refractile and opalescent, making the organism look like a pearl. [source]

But why does it get so big? Well, about 98 % of its body is consisted of a liquid container, called vacuole, that stores nitrates. As mentioned before, these bacteria generate energy from reactions between sulphide and nitrates, but the latter reach the sediment they inhabit only so often:

While the sulfide is available in the surrounding sediment, produced by other bacteria from dead microalgae that sank down to the sea bottom, the nitrate comes from the above seawater. Since the bacterium is sessile, and the concentration of available nitrate fluctuates considerably over time, it stores nitrate at high concentration (up to 0.8 molar) in a large vacuole like an inflated balloon, which is responsible for about 80% of its size. When nitrate concentrations in the environment are low, the bacterium uses the contents of its vacuole for respiration. Thus, the presence of a central vacuole in its cells enables a prolonged survival in sulfidic sediments. The non-motility of Thiomargarita cells is compensated by its large cellular size. [source]

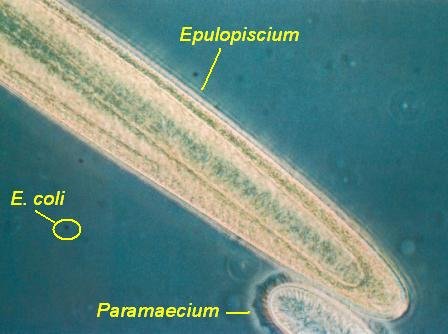

Prior to the discovery of T. namibiensis, the previous holder of the record was Epulopiscium fishelsoni, at 0.2 - 0.7 mm (200–700 μm) long, making it also visible to the naked eye. Epulopiscium means "banquet of fish" from the latin word epulum ("feast" or "banquet") and the latin piscium ("of fish"), a reference to the bacteria's symbiotic relationship with surgeonfish. As for the specific epithet fishelsoni, it is in honor of Lev Fishelson, a Polish-born Israeli ichthyologist who was part of the team who first found the bacterium while studying the intestines of a brown surgeonfish.

Size comparison between Epulopiscium fishelsoni, E. coli and a Paramaecium (credit)

These bacteria have been isolated from many different surgeonfish species from all around the world but the details behind their symbiotic relationship still remain unclear. The prevalent theory is that the bacteria somehow help the fish in breaking down algal nutrients.

What is most interesting about T. namibiensis is probably its unique viviparous (giving birth) reproductive cycle which may also the reason behind it's gigantic size:

Unlike most bacteria, which undergo binary fission, Epulopiscium reproduces exclusively through an unusual form of sporulation in which anywhere from one to twelve daughter cells are grown inside of the parent cell, until the cell eventually lyses (and dies). Although sporulation is widespread among other bacteria (such as Bacillus subtilis) in the phylum Firmicutes, spore formation is usually brought about by overcrowding, the accumulation of toxins in the environment or starvation, rather than a standard form of reproduction. Also, endospores are dormant, while new Epulopiscium cells are active. [source]

And speaking about the world's largest bacteria, I think I have to give a shout out to Syringammina fragilissima. It might not be a bacterium but it is an one-cell organism like bacteria. And not just any single one-celled organism. It's a true behemoth, with the largest ever recorded specimen being 20 cm (8 in) across! Here's a photo of the specimen:

Although it looks like a sponge, it's actually a Xenophyophore, a group of giant multinucleate unicellular organisms found on all major oceans, at depths ranging from 500 to 10,600 meter. Actually, I have made a whole post about S. fragilissima, just click the link to check it out and learn more about it!

So, that's enough talk about gigicantic uni-cell organisms for today. Don't forget to click the various links if you want to learn all there is to know about the organisms mentioned in this post!

More Strange Animal Stuff

If you enjoyed reading this post I am sure you will love some of my previous work. Here are some of my latest posts:

- Clathrus archeri: Weird Alien-Like Eggs Hatch Into Weird Octopus Thing

- Lobster with Pepsi Tattoo Fished In Canada !

- The Jesus Christ Lizard: A Lizard That Can "Walk" On Water

- It's a Scorpion...It's a Fly...It's a Scorpionfly! (Panorpa communis)

- Hagfish Have One Of The Weirdest And Coolest Defense Mechanisms

- Weird MRI Photos, 3-Eyed Beetles, Deep Sea Creatures And Other Cool Animal Stuff

- Can You Guess What Animal Has The Biggest Penis In The World?

- Meet The World's Strangest Ants

"anywhere from one to twelve daughter cells are grown inside of the parent cell, until the cell eventually lyses (and dies)"

Hey, do you think I could grow a mini onceuponatime inside of me, perhaps of finer energy, then anchor my consciousness in it and let the outer worn out old onceuponatime "lyse"? That would be cool!

nah I doubt so :( But if you have enough money you can probably get your self cloned or something and then I would get more funny comments like this!

Oh. that's too bad because that was what I was working on! I guess I'll have to find a new hobby.

Very interesting @trumpman.

As usual, you've blown us away with your awesomeness.

Thanks for teaching us about bacteria today and we look forward to see what's up next.

neat, I got a star :D

Hi, pleas vote me im new in steemit and i want to be good statman in future 🙂

Hi, pleas vote me im new in steemit and i want to be good statmans in future 🙂

You should never beg for votes in the Steemit community. If you create or curate (= find and evaluate) good content using your own words, people will naturally want to vote for you.

If you continue to ask/beg etc. for votes, Steemit members (or bots) will vote you down, and you will be banned. Please don't do this.

This is an international community. If your English is not very good, write in your own language.

a bacteria you can see with the naked eye. Wow !

Being a bit of a science junkie, I loved this post. I really didn't know that some bacterium grew so large!

The reproduction cycle of T. namibiensis is fascinating. I remembered that in dire circumstances many bacteria sort of exploded spewing spores, but this was all new to me!

Thanks for adding to my education!

I dont understand about this post. But I think this is very good.

next time try reading and maybe you will understand

I understand that.this is about becteria.

excellent post I follow you, if you want you can follow me

Thanks for this educative microbiological article. I enjoyed learning a thing or two about these bacterial organisms

Your post has been resteemed to my 2500 followers

Upvote this comment if you like this service

thanks

Cool!

replying just 1 word right after a post comes out (especially one that takes more than 2 minutes to read) makes your comment look like pure attention-seeking spam. something to keep in mind

Sorry, my mistake, but it is simply "cool fact" I didn't knew although I'm the biologist