Writing With Principle Vs. Spectacle

One of the great lessons for any storyteller is the need for the distinction between spectacle and storytelling. This is something that is painful at times, because it requires an incredible amount of self-discipline and locks away a certain amount of ability to correct errors. However, it forces a writer into a habit of choosing good strategies, rather than simply focusing on what seems immediately appealing.

Storytelling with spectacle stands out. It involves high-impact moments as much as possible, and it gives audiences a sample of something much greater than themselves. Movie trailers do this almost without fail; they show pivotal, key, and surprising moments but do not show their context or greater meaning.

The problem with spectacle is that while it stands out, it doesn't stand up. It is not meaningfully important to peoples' lives, and as a result it fails to connect with them. Having spectacle is like having a plate full of dessert without ever eating anything satisfying for a main course. It's not going to produce the emotional and psychological health that a well-written story based on principles of storytelling will have, and it's something that will not foster a later reward in the form of enlightenment or lessons that improve the audience's life.

As a storyteller, there are a few good principles you can consider. When I describe something as belonging to the school of principled writing, I am referring to the practice of choosing to write in accordance with rules and guidelines that promote meaning and beauty. It is a process, and in many ways each writer needs to develop their own ways to align with the principles.

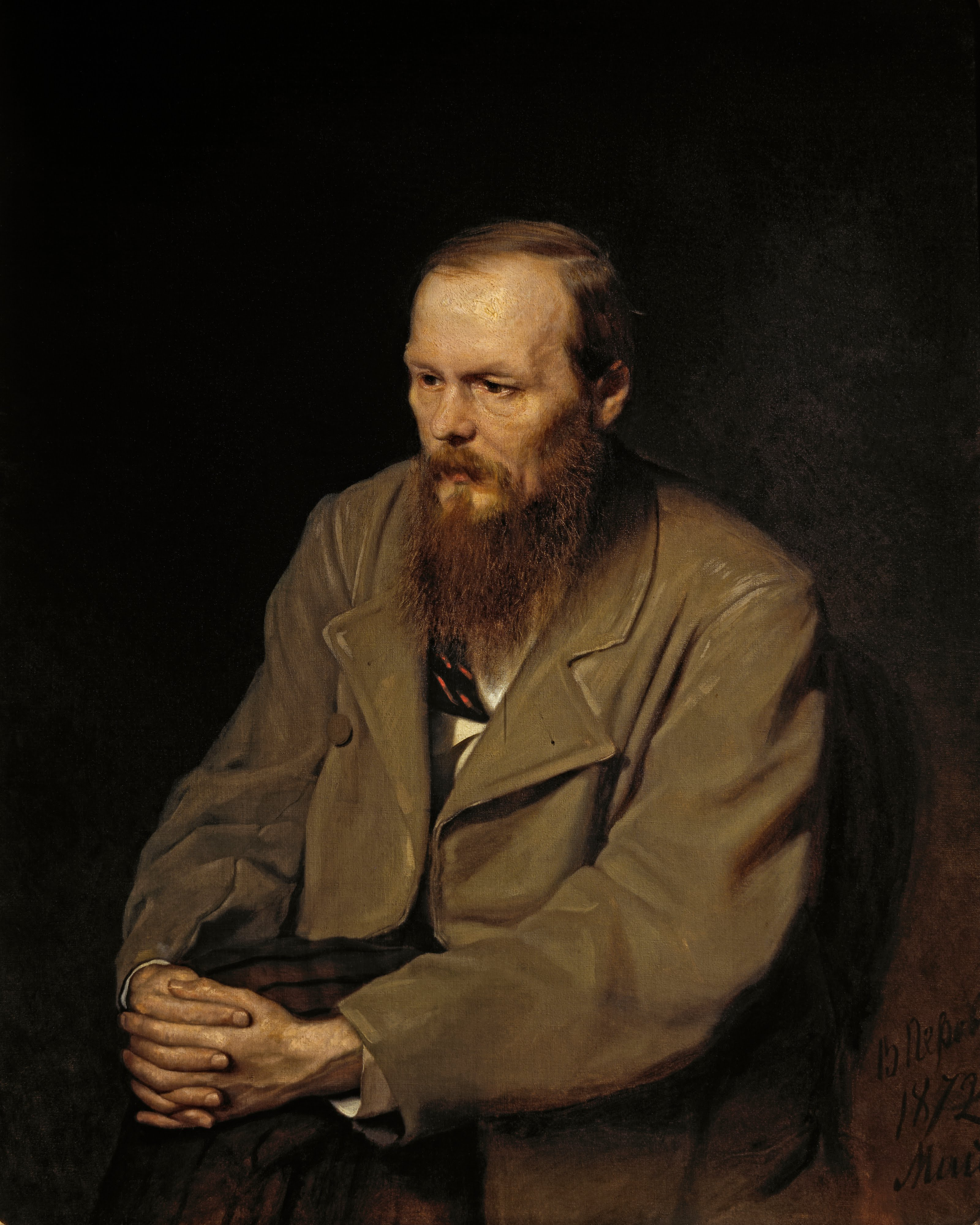

The first is to tell a story with a lesson. You can tie into universal archetypes and link them to your own story. Incorporate elements of the human condition to your work. Tell a story that gives substance and it will persist beyond great spectacle: the novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky are built on substance, not spectacle.

Dostoevsky by Vasily Perov

And it's important to remember that spectacle is garnish. Where things that have no substance fall apart, stories that have substance can add spectacle to foster a greater understanding.

One of the other elements it's important to be aware of when considering what defines principled storytelling versus spectacle storytelling is that there are multiple aesthetic aims of art. I classify these in three ways: appeal, beauty, and the sublime.

Appeal is strictly speaking the superficial factors that make something stand out. This is not bad, but it is the main asset that writers get from spectacle. The emphasis of appeal in modern literature is most immediately clear when one considers the study of genres; a cyberpunk story has appeal to a certain audience, because it is going to follow the tropes and conventions that have appeal to that audience. The grizzled Adam Jensen fighting against conspiracies and seeking universal truth has an appeal that allows for a firm foundation, and his cybernetic abilities provide a spectacle to highlight the main point of the story the writers of the more recent Deus Ex titles wanted to convey.

Beauty is the quality of principled writers in conveying their point well. This is often a matter of craft, where a good author can portray things in a way that is ideal, even if the thing itself is horrible or tragic. War movies like Saving Private Ryan can show the inimitable horror of war in a way that opens our minds to truth, showing us the value of brotherhood and conviction. Beauty is what sticks with people and gets them thinking, but there is something greater.

Before I talk about the sublime, I have to talk briefly about meaning. Appeal and beauty are both ingredients in the sublime, but meaning is important as well. Meaning does not have to be known to the audience, but it must be known to the creator. Great and terrible things, like waterfalls and sunsets, are capable of being sublime to someone who realizes the immense forces these icons represent. If a story has appeal and beauty, but not meaning, it will fall short of the sublime, or at best touch it tangentially as it falls away from the audience's mind. It is not enough to entrust an audience with the duty of finding meaning. They already intend to do this, and you will fail in your goal as a storyteller if they are frustrated by an intentional lack of meaning to your work.

You do not need to pre-ordain the meaning of your work (though if you are able to do so it will likely help improve the quality of your writing), but you do need to look for meaning as you go and pick up on those strands.

When you bring appeal, beauty, and meaning together, you achieve the sublime.

It is difficult to describe the sublime. It is a moment when the audience cannot respond to what you have presented because it is the Truth, both profound and beyond words. If you want to change lives, you need to aim for the sublime, and the sublime lies beyond a conscious pursuit of principled storytelling.

Why Principled Storytelling?

It may seem odd to focus on principled storytelling, when it is also spectacle that is required for the sublime. But spectacle is relatively simple. It is intuitive: you need go no further than to analyze the ordinary speech of people around you to see that their communication is predominated by spectacle: we communicate things that look important, urgent, and demanding. Spectacles do that; in all their forms both wonderful and terrible there is one common thread: they call our attention.

This is also why simply telling a formulaic and principled story will fail, since you will not be able to keep your audience entertained. Disciplined seekers of meaning may miss your point since it is not backed up by the examples that spectacle provides, and anyone who thinks they are simply looking for entertainment will not even consider your writing.

Let's look at four traits of principled storytelling. These are not exclusive or exhaustive: the essence of principled storytelling is to find methods that work well at creating universal stories. Another part of principled writing is finding what your strengths as a writer and storyteller is. Learning from others is wise, but there must be self-awareness alongside of it.

Include a Lesson

One of the great failures that many writers encounter is that their works are damned by faint praise. While their writing may be of sufficient quality, and there are enough moments that foster excitement and short-term discussion, there is nothing that is to be gained by engaging with their work.

A good storyteller will then include a lesson to their story, or at least the starting point for a discussion. Saying that something is presently unsolved can be as much of a lasting point as presenting a known fact to the audience ("Waiting for Godot" comes to mind).

A note from pedagogy: everything that you want to teach someone needs to have an objective.

As a storyteller, you can set this objective to be whatever you want, so long as you unbeholden to notional standards or external factors. You could say that you want people to be able to understand how a kind act can change a life for the better with cascading positive effects (Les Misérables) or that you want to have people appreciate some great historical event's impact in their lives (as most pieces of historical fiction focus on).

If the audience doesn't like your lesson, they will reject it. That is not a condemnation of you, but rather a disagreement with the point you are trying to make. Do not worry overly about this; Orwell's 1984 and Animal Farm brought him criticism from his fellow socialists, but his lesson was meaningful and has since been immortalized in popular cultural and the zeitgeist of academia and public expression.

However, being honest with yourself about whether or not a lesson will bear meaning in other peoples' lives is important. This is a talent and grows with practice, and cannot be taught (or at least cannot be taught by one of my ability).

Use Archetypes

I've already discussed the Hero's Journey but it's important to understand that all stories are full of archetypes, and not solely heroic ones. However, bumbling into archetypes is a much worse method than intentionally using archetypes.

When we eat something, our body has a variety of bacteria and enzymes contained within it that work upon it to break it down into edible chunks. Even so, there are things that we simply do not have the internal environment to break down, and we derive no nutrition from them.

Archetypes are a way to ensure that your audience can break down your story. Adherence to patterns and trends, even conventions and tropes that have fallen out of favor, allows your storytelling to be easily received. You can subvert, manipulate, and deconstruct these concepts within reasonable limits and your audience will still recognize them and be responsive to them.

This process is often subconscious, based on your readers' previous exposure to other storytellers' works that have used archetypes.

It does no harm to a writer if they spend some time researching both literary and psychological archetypes. Doing so will improve their ability to craft vibrant characters: many psychological archetypes, for instance, wind up being too prevalent in a character, resulting in characters that feel "flat" and "static" when they should be "round" and "dynamic", giving the readers plenty of things to feel about. It is a mistake to associate character development with an increase of power and knowledge, or the mere accomplishment of goals; characters who develop overcome the weaknesses inherent to their archetype or change their very nature to fit the demands of their environment; this sort of adaptation is a triumph and makes for a very appealing story.

If it is possible to achieve a peak of meaning at a moment of transfiguration, you may even perform a sort of spectacle while doing so, creating a single event that can encapsulate the sublime.

Elucidate the Human Condition

Another thing you can do is to bring the human condition into your writing. We do not typically read stories of immortals or beings entirely unlike us (and when we do they without fail have tragic elements to their lives that make them interesting and relevant). Even on the rare occasion that we tell stories of these lofty and ancient things we use them as a way to illuminate ourselves. The works of H.P. Lovecraft are of great use to illustrate this: he talks of ancient eldritch things, but his protagonists are almost always confronted not by some demon or monster but the failures of their own mind and understanding. This is often compounded by moral corruption, or at least the temptation toward mortal corruption, and the inexorable nature of the challenges they face.

We all suffer loss, but we all have triumph. I among many other writers have fallen victim to the trap of forgetting this in writing. Even when we center characters around their goals, we fail to provide them with any tragedy or triumph. It is not enough to focus on the human condition only at one moment in your story. Every growth and every setback must be linked to some greater reflection on who we are.

Failure is not just failure. Success is not just success. Failure is a consequence of inability, immorality, or ignorance. Success is the product of growth, right action, or knowledge. When you incorporate this, it makes your story better.

There is also no shame in using actual people as the basis for your story, though you should do so with reverence. You may also retread ancient stories or even play on themes in more modern stories; many of the world's best works of writing were penned in response to something out there that their writers viewed as damaging to society, or as part of a larger image.

Historical events likewise force a confrontation with the human condition.

The absence of a focus on illuminating the human condition is often why many genres of fiction are sneered at by the literary elite. When a swords-and-sorcery novel features spectacle, but no meaningful characters, it is easy to forget that other stories in the genre are not automatically subject to the same flaws.

Avoid the Gratuitous

I am not a particular prude when it comes to others' works, though I hold myself to a practically Puritan standard. There are places where expressions and elements that are considered unsavory can add great meaning to a work and allow it to tackle subjects and concepts that would be impossible to discuss in polite company.

Looking straight at horrible things is necessary to confront them.

But, at the same time it is important to understand that principles are fragile things. Gruesome and vulgar elements can further the pursuit of principles when handled responsibly: war stories fail if we do not talk about the impact that violence, struggle, and loss have, and we cannot discuss that without a certain amount of getting our hands dirty.

Likewise, stories that talk about other moral issues are going to have to contain content that pertains to those subjects.

The problem arises when these things become selling points, when they are gratuitous and supplant the principles of writing. We are drawn to these things like moths to flame; a survival response built into our brains calls us to look at others' misdeeds to learn from them or see if we can get away from them ourselves.

For lack of a better way to put it, sex sells.

But it is also meaningless, and the majority of its portrayals in stories holds appeal without beauty.

As a writer, you need to have appeal, beauty, and meaning to accomplish your supreme goals.

If you want your stories to make the world a better place, you can't be wallowing in filth.

Two-Minute Breakdown

When you write, keep in mind more than just basic mechanics and snapshots of interesting events that might appeal to your reader. Search for and follow a series of rules that help make your writing better. Use archetypes, the human experience, lessons, and careful judgment to keep from having your writing become meaningless.

Thanks for the meaningful post.It is really interesting to read principle vs spectacle.

Navigating college writing can be a real uphill battle – it demands a higher level of critical thinking, research prowess, and overall organization than the essays we were used to in high school. But here’s the plot twist: college life comes with a whirlwind of academic commitments, leaving limited room for tackling the writing Everest. That’s where the hero steps in – writing services. Some students use educational resources to buy a research paper and are completely satisfied with it. These services are like your academic sidekicks, lending a hand to guide you through the maze of academic writing.