Enemies, Right and Wrong: Is the Left a Necessary Enemy of Voluntaryists?

[Originally published in the Front Range Voluntaryist, libertarian sociology column by Richard G. Ellefritz]

In my last installment, titled “Karl Marx, Conflict Theory, and the Coming Battle Between Libertarians and Socialists,” I openly attacked Colorado Springs Socialist, Emma Redman, by critiquing her writing style and criticizing her ideology. In doing so, I made several grammatical errors myself, and I waved my own ideological flags, Weberian social theory (as opposed to Marxian social theory) and voluntaryism (as opposed to statism). So, do two wrongs make a right? Well, it depends on the wrongs, and under whose authority we consider what makes something right (or correct). In this essay, I first quibble over grammatical and stylistic issues in writing, and then proceed toward a discussion of authority. I conclude the essay by addressing the title’s question (and answer). (Readers of my first installment will notice my retention of the device I used and continue to use, but more on that later.)

When writing, one must assume (or is it presume?) the knowledge and perspectives of their readers, but one also must take into account how their readers read. Ms. Redman (if I may assume zir gender) presumed her readers would know the connection between Karl Marx and sociological conflict theory, and I questioned this presumption as logical for her targeted audience yet illogical for broader audiences. Increasingly Leftist in their politics, university professors, social scientists, and sociologists are much more likely (see also here) than the average member of U.S. society to be in the Democratic Party, consider themselves to be liberal progressives, and identify with the writings of and ideologies associated with Karl Marx. Though this fact is not surprising to some, for example, to readers of David Horowitz’s book, 101 Most Dangerous Academics in America, the knowledge of from where, exactly, Marxian ideologies are disseminated in U.S. society is likely lacking (this is my assumption, but one I will pay further attention to in upcoming installments), but perhaps Emma (if I could be so presumptuous as to use her first name) has reason to suspect her readers know and understand this connection, i.e. that thousands of sociology instructors across and throughout U.S. society expose millions of first year college students to Marxian ideology. Perhaps Emma is the victim of Marxian indoctrination, and now a perpetrator of this insidious ideology.

If you have gotten the impression that I, as a sociologist and personally, am opposed to Marxian thought, you are (mostly) correct. While I patently reject the labor theory of value and some other Marxian concepts, I do believe that Marx and Marxists have developed and/or employed several useful concepts and conceptual schema, though not without caveats toward each. For instance, it can be useful, as Marx and Engels did in their manifesto, to divide world history into two competing camps. Afterall, along with many other libertarians, voluntaryists, and anarchists, I tend to view the world along the lines of those who prefer non-aggression as the organizing principle of society and those who either prefer coercion or cannot see the dominant paradigm for what it is, statist to the core. But, perhaps this is my presumption (no, it is not an assumption, for example see here and here), and what really separates society is the relationship to the means of production, as Marx and Engels asserted.

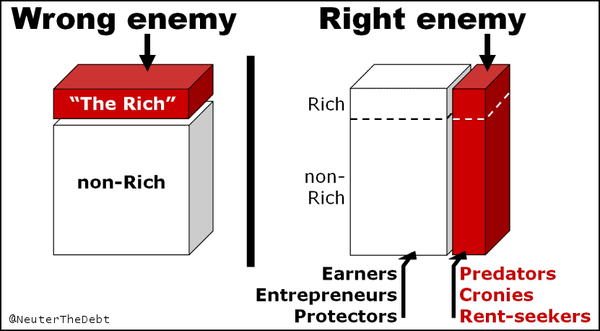

(Figure 1. Enemies, Right and Wrong)

The figure above depicts this in a popular Internet meme, which I referenced at the end of my last installment where I mistakenly stated that the right side of the figure had columns on both the left and right sides as it should due to authoritarianism having both dimensions.

Sociologically, Marxians and Weberians view society in terms of conflict, but whereas the former believe this conflict is between the rich (capitalists) versus the rest (workers), Weberians look toward property ownership (class), lifestyle (status), and access to political parties (power) as dynamic, multi-dimensional and multi-faceted features of societal conflict. From my perspective, both left-wing authoritarianism and right-wing authoritarianism are inexcusable ideologies that rely upon coercion to implement their versions of the social good. Instead of statism in either its Left or Right versions, I believe society should be organized around voluntaryism. Those of us in the middle pretty much just want to get on in our lives in terms of working up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (e.g., see here), but many others in society continue to push toward the use of state power as a solution to the social problems they advocate. As (some) sociologists know well, though, social problems are the outcome of claims-making by interest groups that achieve societal recognition and legitimation. What this means is that one group’s problem is another’s solution (and vice versa), and that some issues are never taken up as a problem due to lack of support or recognition. That is, groups in society raise issues to the level of social problems, and then they seek to remedy those problems.

Marxists of all stripes see economic inequality and capitalism as intertwined social problems, and their solution has always been to increase the bureaucratic power of the state to the point where it has the ability to redistribute, and ultimately abolish, all private property. The vast majority of libertarians, voluntaryists, and anarchists understand that private property is an essential, unalienable feature of human existence, for if you cannot own yourself and the fruits of your labor, you cannot control your destiny and pursue happiness (without harming others, of course). But perhaps that is the point: Marxists want to own you, by any means necessary.

Now, here is where logic and language enter the discussion. Does society exist? Yes, but in what ways, how, and why? These have been questions pondered by sociologists since the field’s inception in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, and they are questions with which I entertain myself. Importantly, if one believes society to be a thing in and of itself, sui generis (as Emile Durkheim thought it), one might also be inclined to believe that society can (and should be) engineered. The reason for this is that society is thought of not as a collection of real, live human beings complete with their own psyches, cognitions, feelings, aspirations, families, friends, occupations, groups, and networks, but rather society is viewed as a series of groups, networks, organizations, and social institutions, each of which is thought of as a component of society.

Therefore, the conclusion is drawn that some entity can and should govern these components to the end that society is benefited, i.e. the state operates toward the greater good. But, how do we define this greater good?

While many sociologists have spilled much ink working toward an understanding of how it is that societal definitions come into existence, most of them owe their livelihoods to the hermeneutics of Max Weber. Weber, as far as I know, did not have a totalizing conception of society. Though he viewed society as composed of bureaucracies and groups of various sorts, he was interested in sociological social psychology that leads humans to engage in social action. Whereas Ludwig von Mises’s Human Action spelled out the preconditions under which people act (i.e. to alleviate discomfort and work toward achieving subjectively defined ends with logical means), Weber focused on social action, noting that some people in some situations act with instrumental rationality (practical means-ends calculations) whereas others act with value-oriented rationality (means-ends motives predicated on cultural values and beliefs). Still, he theorized, people will find themselves motivated by tradition and emotions in other circumstances. Without delving too much deeper into Weberian social theory, it is useful to point out that he had developed similar typologies of authority as well, including rational-legal, traditional, and charismatic origins of authority (they can combine into and emerge from each other in various ways).

What we in the voluntaryist, Non-Aggression Principle camp oppose is not authority per se, but rather the types of traditional and rational-legalistic authority structures that preclude sovereignty and ownership of our own bodies and minds. Right- and Left-wing authoritarians, in whichever socio-economic status level they might be, support and operate the machinery of the state, which is that authority structure that monopolizes the legitimate use of force and violence in society (Weber’s definition). Like social problems, though, it is the state and its supporters that define society and its components in need of its violence. This is indicated by the variants of the word legitimate: Legitimate is an adjective that means to conform to the governing laws and norms, whereas legitimate is a verb that means to justify or to make legitimate. Emma Redman and other Marxists seek to further legitimate state violence to the extent that self-ownership is an esoteric, ancient, or unpopular form of social organization, but this is not necessarily the stance of all Leftists.

As an adherent to left-libertarianism, mainly due to my inclinations toward Weber’s writings on domination and state power, I find that there are allies and potential apologists and recruits among the Left. And so I believe we voluntaryists are not, and should not be necessarily enemies with them. Marxists are a different matter altogether. Whereas a Leftist might believe that government works and can solve problems, they might simply have never been educated about the role of entrepreneurs and market forces in society, and so they have come to believe, for one reason or another, that state power is the primary solution to the social problems they believe need the most attention. We voluntaryists see the state itself as a social problem, and should advocate it as such to as many people as possible, including those on the Left who can come to their senses and understand that taxation, war, and welfare are far more harmful than not, and that they are completely unnecessary in a peaceful, prosperous society built on the tenets of voluntaryism. If we voluntaryists move forward as an exclusive bunch, we will surely atrophy and our cause will whither, but if we open our arms to potential allies, especially those who are or who can be divested of the pernicious assumptions and presumptions of Marxism, we open the potential to diminishing the numbers and effects of the most dangerous authoritarians: Marxists. (Note: I will have more to say about fascists in future installments.)