In Alaska

Earth in Upheaval Revisited – Part 2

Muckraking

When Immanuel Velikovsky slipped his moorings and set out on the virtual voyage of discovery whose log he called Earth in Upheaval, he chose the river valleys of central Alaska as his first port of call.

In 1896 the discovery of gold in this region led to an influx of prospectors in their thousands. In order to reach the gold-bearing gravel-beds, these prospectors had to remove an overburden of permafrost, which they dubbed muck:

This “muck” contains enormous numbers of frozen bones of extinct animals such as the mammoth, mastodon, super-bison and horse. (Rainey 305)

... there is ample evidence that at least portions of this material were deposited under catastrophic conditions. (Hibben 1943:256)

Velikovsky’s sources for this information were two papers that appeared in American Antiquity in the 1940s:

Froelich Rainey, Archaeological Investigation in Central Alaska, American Antiquity, Volume 5, Number 4 (April 1940), pp 299-308, Society for American Archaeology, Salt Lake City UT (1940)

Frank C Hibben, Evidences of Early Man in Alaska, American Antiquity, Volume 8, Number 3 (January 1943), pp 254-259, Society for American Archaeology, Salt Lake City UT (1943)

Velikovsky cites Hibben’s paper as Evidence of Early Man in Alaska, a mistake that many of his followers and detractors have repeated. A longer and more detailed account of Rainey’s investigations appeared in 1939 in Volume 36 of the Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. In 1946 Hibben published a popular account of his Alaskan expedition in The Lost Americans.

Froelich Rainey was Professor of Anthropology at the University of Alaska from 1935 to 1942. After a distinguished career in academia, he became the host of a successful television show, What in the World, in which expert contestants were required to identify archaeological artifacts. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology, where Rainey worked after the War, has compiled a YouTube Playlist of excerpts from the show.

Frank Cumming Hibben was a professor of anthropology at the University of New Mexico and the first director of the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology. His career was marred by allegations of scientific fraud during the excavation of Sandia Cave, New Mexico, in the 1930s and ’40s. His expedition to Alaska, which is the object of our interest, also generated some controversy.

Alaskan Muck

The Alaskan muck deposits comprise a permafrost of dark gray to black silt, principally derived from the local schist bedrock, interspersed with a considerable quantity of organic matter (vegetation, bones and animal carcasses), ice lenses, peat lenses, and volcanic ash. They vary in thickness from 1-100 m, cover a significant portion of central Alaska, and are believed to be of late glacial or early post-glacial age.

How were these deposits of bone-riddled muck created? Rainey was not prepared to hazard a guess:

No adequate explanation of the age of these deposits nor the manner in which they were formed can be given at present. (Rainey 1940:305)

Judging from the stratigraphy of the muck deposits and the faunal remains contained in them, it has been concluded that they were laid down during late Pleistocene and Recent times, but an explanation

of the origin of the deposits cannot yet be given. (Rainey 1939:390)

Hibben, however, was not as cautious as his colleague:

The deposits known as muck may be definitely described, in the opinion of the writer, as loess material. All characteristics seem to indicate a wind-borne origin from comparatively local sources, as the material resembles underlying bedrock. The outwash plains of the local glaciations are likely points of origin for this material. (Hibben 1943:255)

But on the very next page he backtracked and even seemed to contradict himself in a passage which Velikovsky quoted:

Although the formation of the deposits of muck is not clear, there is ample evidence that at least portions of this material were deposited under catastrophic conditions. Mammal remains are for the most part dismembered and disarticulated, even though some fragments yet retain, in their frozen state, portions of ligaments, skin, hair, and flesh. Twisted and torn trees are piled in splintered masses ... At least four considerable layers of volcanic ash may be traced in these deposits, although they are extremely warped and distorted. (Hibben 1943:256)

In an earlier paper, Hibben had made the important deduction that the Alaskan muck deposits were not created by a single catastrophic event but by a series of events separated by quiescent periods:

The torn and lacerated limbs and trunks of these trees give every indication of violent but not lengthy transportation to their present situation. Intermittently, however, with these violent erosional evidences, are lenses of peat apparently representing a static ground level at that particular stratum for at least several years. The total of these evidences indicates the alternate and intermittent periods of violent erosion such as would dismember animal remains and splinter trees, interspersed with other periods of comparative quiescence so as to allow the growth of “forests” and peat bogs in the same area. (Hibben 1941:154)

Hibben identified the bones of more than a dozen vertebrates in the muck:

Animals at present identified from the Alaskan muck include the mammoth, mastodon (although not nearly so common as the mammoth), horse, at least three species of bison, (Bison crassicornis, Bison occidentalis, and Bison alleni), two species of musk ox, saber toothed tiger, lion, camel, gazelle, antelope, an extinct bear, sheep, and a number of rodent forms. (Hibben 1941:153)

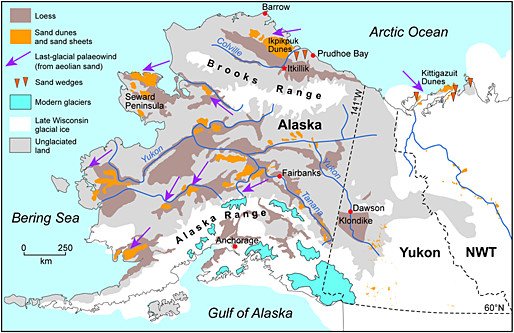

Loess

Loess is a technical term used by geomorphologists and geologists to describe wind-borne deposits of clay and silicate matter. Hibben’s characterization of the inorganic content of the Alaskan muck as loess has been reaffirmed by subsequent studies. If the outwash plains of the local glaciations are likely points of origin for this material and if at least portions of this material were deposited under catastrophic conditions, then it is perverse not to conclude that we are looking at the result of catastrophic post-glacial floods, which washed away the upper layers of Alaskan loess and swept up all the flora and fauna that lay in their path.

Velikovsky discusses loess, briefly, in Chapter VI of Earth in Upheaval, so this is a subject we will be returning to in due course.

Doubting Hibben and His Muck

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort by some uniformitarians to discredit Hibben’s findings in Alaska, and to pour cold water on the theory that the end of the Ice Age was punctuated by a global catastrophe. One man who appears to have made this his mission in life is Paul V Heinrich, a geologist and archaeologist at Louisiana State University. He calls his online blog The E-Pistles of Paul: his admirers consider this a witty title : to his detractors, it reflects the high opinion he has of himself.

Heinrich has never published a peer-reviewed paper disputing Hibben’s findings. In fact, none of his papers are concerned with Alaskan geology.

A good example of Heinrich’s attitude towards Hibben is provided by this lengthy polemic: The Mythology of Hibben and the Alaskan Muck, which was posted on Google Groups by Stratigrapher, who identifies himself only as Douglas. This was clearly copied and pasted from Heinrich’s blog. A revised version of this article appeared on Heinrich’s blog in 2007: The Imaginary Mucks from Alaska and Siberia.

More than two dozen sources are cited in Heinrich’s articles on Hibben: a lot of research is required if we want to get to the bottom of this debate:

If a person looks at the numerous scientific publications that have been published in the scientific literature in the 62 years since [Hibben’s] Lost Americans was published, a person finds that descriptions made by Hibben (1946, 1951) of the Alaskan muck have not been collaborated by any later researcher, i.e. Bettis et al. (2003), Busacca et al. (2004), Muhs and Bettis (2003), Muhs et al. (2003), Pewe (1955, 1975a, 1975b, 1989), Westgate et al. (1990, 2003), and many others. They have all found that the “huge numbers of late Pleistocene animal carcasses and splintered trees” reported in Hibben (1946) and their mangled condition are grossly overexaggerated by him and the various books and web pages that cite Hibben (1943, 1946). (Paul V Heinrich)

Does this mean that Hibben’s reports of huge numbers of late Pleistocene animal carcasses and splintered trees and their mangled condition are essentially correct but simply exaggerated?

What actual criticisms do Bettis et al, Busacca et al, etc make of Hibben’s claims? Let’s take them one by one:

- E A Bettis, D. R. Muhs, H. M. Robert, and A. G. Wintle, Last Glacial Loess in the Conterminous USA, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 22, Issue 18, pp 1907-1946 (2003)

This paper does not mention Hibben or the Alaskan muck deposits.

- A J Busacca, J E Beget, H W Markewich, D R Muhs, N Lancaster, and M R Sweeney, .R., 2004, Eolian Sediments, in A R Gillespie, S C Porter, and B F Atwater (editors), The Quaternary Period in the United States, pp 275-309, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2004)

This paper does not mention Hibben or the Alaskan muck deposits. In discussing the Alaskan loess, which underlies Hibben’s muck, it makes one brief reference to the permafrost:

Most Alaskan loess is associated with present or past occurrences of ice-rich permafrost (Fig. 9). In some instances, thick deposits of loess and reworked loess contain specimens of frozen Pleistocene megafauna, including mammoth, bear and bison ... Frozen Alaskan loess deposits also contain buried forest beds, consisting of horizons of logs, branches, leaves, and other biologic materials, as well as peat, beaver-chewed wood, and paleosols correlative with the last interglaciation ... (Busacca et al 288)

I don’t see how this has any relevance to Hibben’s work. It certainly does not dispute Hibben’s claim that the muck contained reworked loess.

- D R Muhs, and E A Bettis III, Quaternary Loess-Paleosol Sequences as Examples of Climate-Driven Sedimentary Extremes, in M A Chan and A W Archer (editors), Extreme Depositional Environments: Mega End Members in Geologic Time, pp 53-74, Geological Society of America Special Paper 370 (2003)

This source does not mention Hibben or the Alaskan muck deposits. Like the first two sources, it is concerned with the underlying loess, not the muck.

- D R Muhs, T A Ager, E A Bettis III, J McGeehin, J M Been, J E Beget, M J Pavich, T W Stafford Jr, D S P and Stevens, Stratigraphy and Paleoclimatic Significance of Late Quaternary: Loess-Paleosol Sequences of the Last Interglacial-Glacial Cycle in Central Alaska, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 22, Issue 18, pp 1947-1986 (2003)

I have not been able to access an online copy of this paper, but the abstract makes it clear that the paper is concerned with the production and accumulation of Alaskan loess over the past three million years.

- Troy L Péwé, Origin of the Upland Silt near Fairbanks, Alaska, Geological Society of America Bulletin, Volume 66, Number 6, pp 699-724 (1955)

This paper does not mention Hibben or Alaskan muck. As its title indicates, its subject is upland silt, whereas the muck was deposited downstream in the valley-bottoms of the great Alaskan rivers. According to the abstract, Péwé surmises that the silt around Fairbanks is of aeolian origin—in other words, it is loess. This is precisely what Hibben claimed. The real question is: how did some of this loess end up in the low-lying muck? Péwé’s guess:

Much silt has been reworked and moved by stream erosion into valley bottoms where it forms a fill 10–300 feet [3-100 m] thick. (Péwé 1955:699)

But this does not explain how the entrained flora and fauna were disarticulated, dismembered and splintered. Gradualist stream erosion will not do that. Péwé never addresses this problem.

- Troy L Péwé, Quaternary Geology of Alaska, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 835, United states Government Printing Office, Washington (1975a)

Here Péwé does cite Hibben’s 1943 paper in connection with the discovery of vertebrate remains in Alaska:

Alaska, like northern Siberia, has long been famous for the abundant remains of extinct Pleistocene mammals, found in frozen deposits along major rivers and in the valleys of many minor streams ... Most of the remains of land mammals are from the unglaciated part of Alaska (fig. 42). Such distribution is to be expected because animals were mostly absent .in glaciated areas during glacial maximums and glacial advances tended to destroy or cover earlier fossil remains. The greatest collection of vertebrate specimens is from the Fairbanks area, where tens of thousands of specimens have been collected during the past 30 years. For example, in 1938, a typical year, 8,008 cataloged specimens weighing about 8 tons were collected by 0. W. Geist and shipped to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (University of Alaska, ((Collegian," 1938, fall). Partial lists of mammals from the Fairbanks area were given by Frick (1930, 1937), Wilkerson (1932, p. 422), Mertie (1937, p. 191), Stock (1942), Hibben (1943), Taber (1943, p. 1487), Skinner and Kaisen (194 7), Skarland (1949, p. 132-133), Pewe (1952a, table 4), Geist (1953), Pewe and Hopkins (1967), and Guthrie (1968a). The geological literature (U.S. Geological Survey Bulletins) in Alaska dealing with early placer mining activities mentions in passing that bones of extinct animals such as mammoth, mastodon, bison, horse, and others were found in many localities in addition to the Fairbanks area. (Péwé 1975a:91 ... 92)

On the question of Alaskan muck, Péwé writes:

A large part of the loess falling on summits and slopes of hills has been washed into valley bottoms to form thick deposits of bedded to massive silt that is rich in organic debris. These deposits locally are called muck ... The bedded character of the valley-bottom silt has been used as evidence to support hypotheses for the marine, lacustrine, and residual origin of loess ... In Wisconsinan time, additional loess was deposited on the uplands, and much loess was retransported to valley bottoms to form a carbonaceous, fetid, perennially frozen deposit, locally termed “muck” (fig. 20). This valley-bottom facies of loess of Wisconsinan age is 3-46 m thick and contains abundant vertebrate and plant fossils, including partial carcasses of vertebrates that were entombed in the silt and perennially frozen. The most common vertebrate remains in the muck of Wisconsinan age, in order of their abundance, are those of bison, mammoth, and horse. The retransported silt (valley-bottom facies) of Wisconsinan age contains many ice wedges 0.3-3 m wide and as much as 10m long. (Péwé 1975a:37 ... 38 ... 42)

Péwé does dispute any claims that the animal remains are unnaturally abundant, and he again attributes the accumulation of the muck in the valley-bottoms to gradualist processes:

Most of the mammal remains from the Fairbanks area are from retransported valley-bottom silt of Wisconsinan age rich in organic material ... Most of the fossils are found in valley bottoms, owing to gradual downslope movement. Some transportation also occurs down the stream axes, and the greatest concentrations are found where small tributaries join large creeks. These great accumulations of bones are thus not “animal cemeteries” or unnatural concentrations. (Péwé 1975a:97 ... 98)

As in Péwé (1955), he does not even address the question of the condition of the mammal remains, which was the basis for Hibben’s claim that some of the muck was laid down under catastrophic conditions.

- Troy L Péwé, Quaternary Stratigraphic Nomenclature in Central Alaska, Geological Survey Professional Paper 862, United States Government Printing Office, Washington (1975b)

This paper does not mention Hibben. Péwé does briefly discuss the Alaskan muck deposits near Goldstream Creek, about 10 km north of Fairbanks:

The Goldstream Formation is a valley-bottom accumulation of loess in almost all creek and small river valleys in central Alaska ... [It] consists of perennially frozen retransported bedded loess that contains abundant minute carbonized organic fragments and some peat lenses, sticks, and twigs ... The Goldstream Formation is the greatest repository of remains of Pleistocene vertebrates in Alaska, if not in North America. Various conditions favored the accumulation of vertebrate remains of Wisconsinan age in this deposit: (1) The Goldstream Formation is a valleybottom deposit, and most bones of the vertebrates are gradually transported downslope to valley bottoms; (2) the older valley-bottom deposits of Illinoian age have been mostly removed; and (3) sediments of the Goldstream Formation froze soon after deposition. The most abundant remains are those of bison; remains of mammoth and horse are next in abundance ... The famous partial carcasses of Pleistocene mammals were found in this formation (Geist, 1940; Péwé, 1952, p. 123-126; 1966; 1975, table 13). (Péwé 1975b:)

- Troy L Péwé, Quaternary Stratigraphy of the Fairbanks Area, Alaska, in L D Carter, T D Hamilton, and J P Galloway (editors), Late Cenozoic History of the Interior Basins of Alaska and the Yukon, pp 72-77, U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1026 (1989)

This paper does not mention Hibben. Again, Péwé does briefly discuss the Goldstream Formation, but adds nothing of substance to his earlier treatment.

I am beginning to detect a pattern here. None of Heinrich’s sources has found that Hibben’s claims are greatly overexaggerated. Most of them never mention Hibben or cite any of his papers. They are not even concerned with the Alaskan muck. Their subject is the wind-borne loess, which had been accumulating for millions of years before the muck was created. If there is loess in the muck—as Hibben correctly surmised—it is surely because previously accumulated loess was eroded and entrained by the glacial floods that created the muck. When the catastrophic floods occurred, they swept away the top layers of loess, as well as all the flora and fauna that lay in their path.

Incidentally, other issues of Geological Society of America Bulletin do contain papers that directly address the question of the origin of the Alaskan muck deposits. One of these, Origins of the Muck-Silt Deposits at Fairbanks, Alaska by Ralph Tuck, makes a clear distinction between the muck and the loess:

The extensive gold-bearing gravel deposits in the Fairbanks district are covered with a muck-silt overburden varying from a few feet [1 m] to over 200 feet [60 m] thick ... The overburden is of two types—muck and silt. The muck, which is frozen, occupies the present stream valleys and lies unconformably upon, or grades into, the silt, which is unfrozen and occurs on the lower hill-slopes. The inorganic material in the two deposits is essentially the same, but the muck contains about 50 per cent ice and vegetable material as well as an abundant Pleistocene fauna.

The origin of the muck and silt has long been obscure because of poor exposures and the complications of sub-Arctic solifluction processes. It now seems certain that the silt is of aeolian origin, while the inorganic material of the muck consists principally of wind-blown particles that have been reworked by creep, sheetwash, and stream action. A large part of the interior of Alaska is unglaciated; the deep muck-silt deposits occur in this unglaciated area and are probably a result of Pleistocene glaciation in nearby localities, as conditions were then ideal for aeolian deposition. (Tuck 1295)

Probably.

Heinrich insists that there no distinction between the loess and the muck:

There is absolutely nothing in this paper that relates to the Alaskan loess deposits, which Hibben called “muck”. In fact, there are innumerable OSL, radiocarbon dates, and dated ash beds that clearly demonstrate that Hibben’s “muck” deposits predate the Younger Dryas event by tens of thousands of years to over 3 million years. (Paul V Heinrich)

Even some catastrophists have conceded that Hibben, who was not a geologist, did not appreciate the important distinction between the Alaskan loess, which had been accumulating for millions of years, and the muck deposits, which overlie the loess and were created in late glacial or early post-glacial times.

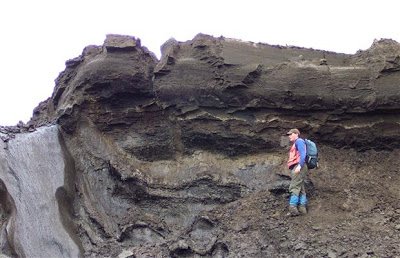

Stratification of Alaskan Muck

Heinrich makes much of the stratified or layered nature of the muck, which argues for a gradualist formation over a long period of time:

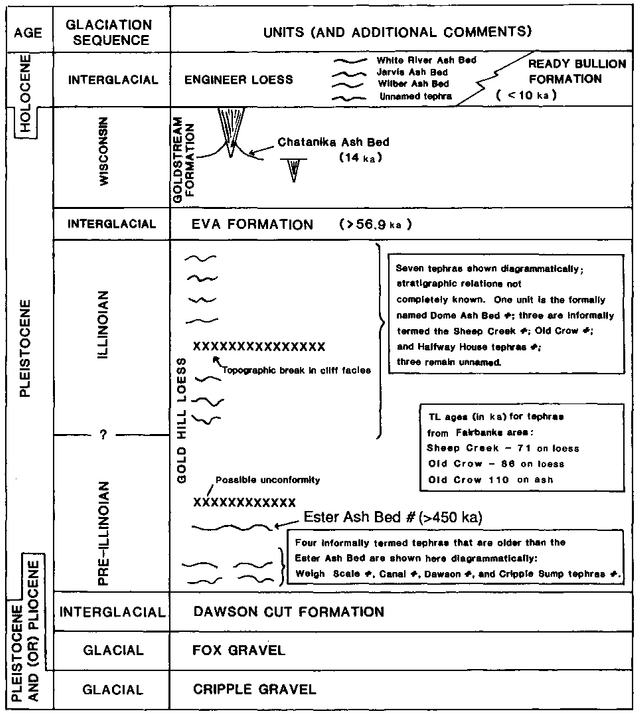

In the real world, the so-called “Alaskan muck” is a well-ordered, layer-cake sequence of layers of loess, colluvium, and solifluction deposits separated by paleosols, erosional unconformities, and buried forests with in situ stumps. These layers are illustrated by figures 20 and 29 of Pewe (1975b), figure 4 of Pewe et al. (1997), and the measured sections of Westgate et al. (1990). Within what Hibben (1943, 1946) refers to as the “Alaskan muck”, geologists readily recognized 7 well-defined, distinct layers. The major layers are the Ready Bullion Formation, Engineer Loess, Goldstream Formation, Gold Hill Loess, and the Fairbanks Loess. They consist of silt, which [has] been demonstrated to consist of a combination of wind-blown silt called “loess” and sediments moved down-hill by slopewash and solifluction. Lying between these major units are Dawson Cut and Eva Formations, which consist of buried forests that are rooted in “fossil” soils, which are called “paleosols”. Lying buried beneath the loess and filling buried valleys are gold-bearing stream gravels, which have been divided into the Tanana Formation, Fox Gravel, and Cripple Gravel. These layers are jumbled only where the have been disturbed by either thermokarst, landslides, solifluction, gold mining, or some combination of these processes. (Paul V Heinrich)

The problem with this is that it conflates the late glacial muck with both the earlier loess that had been accumulating for millions of years and the more recent loess that is still accumulating today, as though they were all Hibben’s muck. Of Stratigrapher’s 7 well-defined, distinct layers only the Goldstream Formation and the Fairbanks Loess are late glacial, and of these only the Goldstream Formation is low-lying (Péwé 1989:74). The Ready Bullion Formation, which overlies the Goldstream Formation in the valley-bottoms, is early post-glacial. Hibben’s muck comprises, at most, the top of the Goldstream Formation and the bottom of the Ready Bullion Formation. Significantly, neither of these two Formations is well-stratified throughout:

Overlying the Eva Formation is the Goldstream Formation (Pewe, 1975a), a widespread deposit of perennially frozen, poorly bedded, organic-rich, gray to black retransported loess that is 10 to 35 m thick. Vertebrate remains including mammoth, horse, and bison are common in this deposit, and rare frozen carcasses also are present ... Unconformably overlying the Goldstream Formation is the Engineer Loess (on hill slopes) and the Ready Bullion Formation (in valley bottoms). Both of these units are of Holocene age and have basal radiocarbon ages of about 10 ka (Pewe, 1975a) ... The Ready Bullion Formation is a poorly to well-stratified, perennially frozen, organic-rich, retransported loess. (Péwé 1989:74, emphasis added)

Elsewhere, Péwé characterizes these deposits thus:

A large part of the loess falling on summits and slopes of hills has been washed into valley bottoms to form thick deposits of bedded to massive silt that is rich in organic debris. These deposits locally are called muck ... (Péwé 1975a:37)

In the field of geology, massive is a technical term:

massive – a description applied to a homogeneous rock, lacking internal structure or layers.

In other words, some of the Alaskan muck is bedded and some is unbedded. This implies that some of the muck deposits were laid down by gradualist processes and some by catastrophist processes. This is precisely what Hibben said:

... at least portions of this material were deposited under catastrophic conditions. (Hibben 1943:256)

The total of these evidences indicates the alternate and intermittent periods of violent erosion such as would dismember animal remains and splinter trees, interspersed with other periods of comparative quiescence ... (Hibben 1941:154)

Muck, Mammoths and Men

As will become clear in future articles in this series, Velikovsky believed that the last glaciation ended abruptly about 3500 years ago. This is the cornerstone of the Short Chronology. So it is not surprising to read the following in Earth in Upheaval:

In various levels of the muck, stone artifacts were found “frozen in situ at great depths and in apparent association” with the Ice Age fauna, which implies that “men were contemporary with extinct animals in Alaska” [Rainey 307]. Worked flints, characteristically shaped, called Yuma points, were repeatedly found in the Alaskan muck, one hundred and more feet [30 m] below the surface. One such spear point was found there between a lion’s jaw and a mammoth’s tusk [Hibben 1943:257]. Similar weapons were used only a few generations ago by the Indians of the Athapascan tribe, who camped in the upper Tanana Valley [Rainey 301] “It has also been suggested that even modern Eskimo points are remarkably Yuma-like” [Hibben 1943:259], all of which indicates that the multitudes of torn animals and splintered forests date from a time not many thousand years ago. (Velikovsky 1977:3)

Velikovsky’s conclusion rests on two premises:

- Yuma-like points are remarkably similar to modern Inuit points.

- Yuma-like points found in the Alaskan muck can be associated with glacial megafauna.

The first of these premises is subjective, and Hibben never told us who first suggested that modern Eskimo points are remarkably Yuma-like. All primitive projectile points resemble one another to some extent: this is simply unavoidable, given the nature of the material and the common purpose to which such points are put. The following pictures illustrate the obvious similarities and the obvious differences between points retrieved from Alaskan muck deposits (left), Yuma or Eden points from Yellowstone Lake (centre), and Inuit points from the 20th century (right):

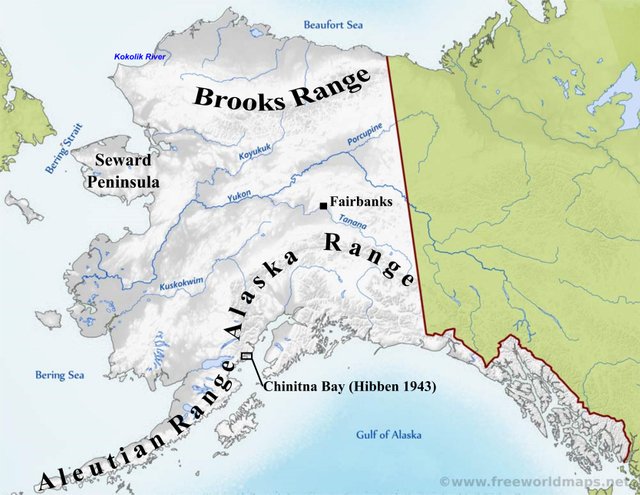

The second premise has also been contested. The only paper I have come across that actually takes issue with Hibben’s work is A Reported Early-Man Site Adjacent to Southern Alaska’s Continental Shelf: A Geologic Solution to an Archeologic Enigma, which appeared in Quaternary Research in 1978. In this paper, the authors—Robert M Thorson, David C Plaskett and E James Dixon Jr—claim that the deposits Hibben identified in Chinitna Bay were much more recent than he claimed and that the bones he identified as mammoth bones were of uncertain identity or provenance:

An extensive ancient archeologic site containing lithic artifacts and associated with mammoth remains was reported at Chinitna Bay, southern Alaska in 1943. The presence of such a site adjacent to the continental shelf at the base of the rugged Aleutian Range suggested that humans may have inhabited the inner shelf environment during the late Pleistocene at times of lowered sea level. Because of the site’s potential significance, an interdisciplinary research team relocated and reinvestigated the area in 1978, but failed to find evidence of prehistoric human habitation. Geologic studies and radiocarbon dating indicate that the strata reported at the site are intertidal in origin, very late Holocene in age, and have undergone significant tectonic movement in the recent past. These observations indicate that the previously published observations of the Chinitna Bay site are probably invalid. (Thorson et al 259)

According to Thorson et al’s radiocarbon dates, Hibben’s site is less than 1000 years old. But if the deposits are so recent, how can they contain mammoth bones? The current mainstream view is that the woolly mammoth, Mammuthus primigenius became extinct in mainland Alaska around 10,000 BCE. In order to fit these deposits of very late age into the current paradigm, Thorson et al have no option but to dispute Hibben’s claim that the deposits at Chinitna Bay contained the bones of mammoths:

Association between the reported mammoth remains and the “Yuma-like” projectile points was probably presumed because both lithic and faunal materials were independently thought to indicate considerable antiquity. Both of these fundamental assumptions now appear questionable because: (1) no longer is the Yuma type considered as a useful or homogenous typological or temporal concept in the Southwest United States where it was defined (Wormington, 1957), and its applicability to Alaskan prehistory has not been demonstrated: and (2) the occurrence of modern large mammal bones (beluga whale) in the center of the reported site area brings into serious question Hibben’s undocumented identification of the bone fragments as mammoth. (Thorson et al 272)

This is all very interesting and all very irrelevant. Hibben’s site at Chinitna Bay does not contain Alaskan muck—at least not the sort of muck we have been discussing—whereas projectile points have indisputably been recovered from the Alaskan muck deposits in many other parts of the state. The presence of Paleo-Indians in Alaska before the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna is now widely conceded. But none of this has any bearing on the timing of these events, so let us drop the matter and move on.

Citations of Hibben

According to Google, Hibben’s paper has been cited 29 times since its publication in 1943. This figure includes citations by catastrophists such as Velikovsky, Vine Deloria Jr and Charles Hapgood. As far as I can tell from their titles and abstracts, none of these works disputes Hibben’s evidence of catastrophism in the formation of at least some of the Alaskan muck deposits. The majority of these works are concerned with archaeological questions and evidence of the passage of early humans through this region.

Rainey’s paper has been cited 130 times since it appeared in 1940. He appears to have passed through the Alaskan-muck controversy without any lasting stain to his academic reputation. The vituperation of the gradualists has been reserved for Hibben alone, it seems.

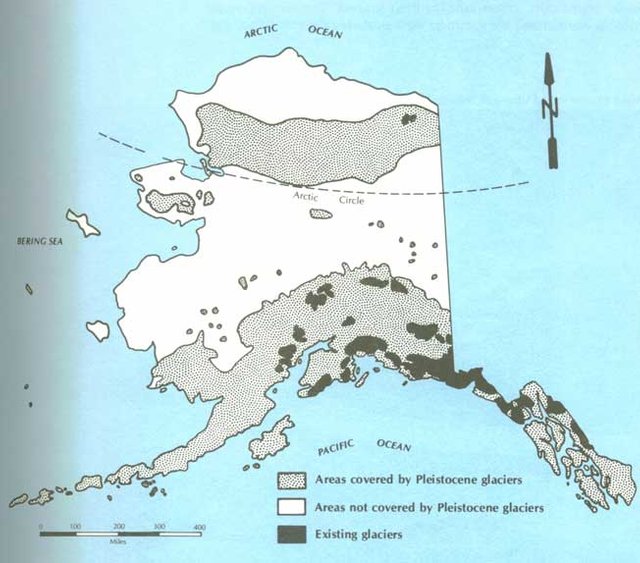

Unglaciated Alaska

Note that the vast region of Alaska in which the muck deposits were created was unglaciated:

The various extensions and lobes from the Continental ice centers of the last portion of the Pleistocene in North America never covered the central sector of Alaska. With the exception of the Brooks Range, the Alaska Range, and certain of the volcanic areas of the Aleutian Range, the northern portion of Alaska was ice free during the period known in the south as the Wisconsin. The whole central Yukon sector, large portions of the Arctic coast, the Seward Peninsula area, and apparently sporadic bits on the coast near Cook Inlet, were not only ice free but also provided essentials of plants, mammals, and surface features, as would be favorable for habitation. Contrary to popular belief, from all available evidence climatic conditions in the Yukon Valley in the last portion of the Pleistocene were essentially the same as they are today. Most of the evidences for this statement have been derived from the so-called Alaskan muck. (Hibben 1943:255)

How could large tracts of Alaska remain unglaciated at a time when there were thick sheets of ice covering Ireland and New York? That is a mystery to be puzzled over in a future article.

It is also hard to explain how lions, camels and gazelles could have thrived in Alaska under climatic conditions essentially the same as today’s.

Summary

The Alaskan muck deposits still have much to tell us about conditions during the late glacial and post-glacial periods, but they will not give up their secrets without further investigation. Since Rainey’s and Hibben’s expeditions in the forties, most field geologists and geomorphologists who have visited central Alaska have focused their attention not on the muck but on the underlying loess. Far from refuting Hibben’s claims that at least some of the muck was deposited under catastrophic conditions, they have simply ignored them. In my research I did not come across a single paper that openly disputed Hibben’s descriptions of disarticulated and dismembered carcasses or twisted and splintered trees.

The muck is still there. It should not be too difficult to resolve this issue once and for all.

Thorson et al have exposed some errors made by Hibben, but only in relation to his archaeological excavations at Chinitna Bay, which does not contain muck deposits. Péwé argued that the quantities of animal remains in the muck were not unnatural and that gradual erosion could explain the deposits, but he never addressed the question of shattered carcasses and uprooted trees. Layering of the muck does not preclude catastrophic origins: it simply reflects the fact that the muck was not created in a single event.

In my opinion, the Alaskan muck deposits do not require a global catastrophe for their formation : nor do they imply a major irruption of the sea, as Velikovsky believed. They are adequately explained by a series of regional late glacial flood events. These events were sudden and catastrophic, and possibly on the same scale as the Missoula Floods that created the Channeled Scablands of Washington State. Any gradualist explanation of these deposits must first refute Hibben’s evidence of catastrophic conditions.

Bearing in mind the controversy that still surrounds this subject—a controversy that I have neither the expertise nor the resources to resolve—I am reluctant to build a theory of late glacial catastrophism on nothing but Alaskan muck. Corroboration is required.

Fortunately, Alaska is not the only place in the world where the disarticulated remains of megafauna are alleged to have been found. Siberia, too, has its post-glacial boneyards, and that is where we must pick up the thread of our story.

References

- E A Bettis, D. R. Muhs, H. M. Robert, and A. G. Wintle, Last Glacial Loess in the Conterminous USA, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 22, Issue 18, pp 1907-1946 (2003)

- A J Busacca, J E Beget, H W Markewich, D R Muhs, N Lancaster, and M R Sweeney, .R., 2004, Eolian Sediments, in A R Gillespie, S C Porter, and B F Atwater (editors), The Quaternary Period in the United States, pp 275-309, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2004)

- Frank C Hibben, Archaeological Aspects of the Alaska Muck Deposits, New Mexico Anthropologist, Volume 5, Number 4 (October-December 1941), pp 151-157 The University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL (1941)

- Frank C Hibben, Evidences of Early Man in Alaska, American Antiquity, Volume 8, Number 3 (January 1943), pp 254-259, Society for American Archaeology, Salt Lake City UT (1943)

- Frank C Hibben, The Lost Americans, Thomas Y Crowell Co, New York (1946)

- D R Muhs, and E A Bettis III, Quaternary Loess-Paleosol Sequences as Examples of Climate-Driven Sedimentary Extremes, in M A Chan and A W Archer (editors), Extreme Depositional Environments: Mega End Members in Geologic Time, pp 53-74, Geological Society of America Special Paper 370 (2003)

- Troy L Péwé, Origin of the Upland Silt near Fairbanks, Alaska, Geological Society of America Bulletin, Volume 66, Number 6, pp 699-724 (1955)

- Troy L Péwé, Quaternary Geology of Alaska, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 835, United states Government Printing Office, Washington (1975a)

- Troy L Péwé, Quaternary Stratigraphic Nomenclature in Central Alaska, Geological Survey Professional Paper 862, United States Government Printing Office, Washington (1975b)

- Troy L Péwé, Quaternary Stratigraphy of the Fairbanks Area, Alaska, in L D Carter, T D Hamilton, and J P Galloway (editors), Late Cenozoic History of the Interior Basins of Alaska and the Yukon, pp 72-77, U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1026 (1989)

- Froelich Rainey, Archaeology in Central Alaska, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume 36, Part 4, pp 351-405, The American Museum of Natural History, New York (1939)

- Froelich Rainey, Archaeological Investigation in Central Alaska, American Antiquity, Volume 5, Number 4 (April 1940), pp 299-308, Society for American Archaeology, Salt Lake City UT (1940)

- R M Thorson, D C Plaskett, F C Dixon Jr, A Reported Early-Man Site Adjacent to Southern Alaska’s Continental Shelf: A Geologic Solution to an Archeologic Enigma, Quaternary Research, Volume 13, Number 2, pp 259-273, (1978)

- Ralph Tuck, Origins of the Muck-Silt Deposits at Fairbanks, Alaska, Geological Society of America Bulletin, Volume 51, Issue 9, pp 1295-1310 (1940)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Doubleday & Company, New York (1955)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1977)

Image Credits

- In Alaska: © 2017 www.freeworldmaps.net, Fair Use

- F Rainey: © 2016 University of Alaska, Fair Use

- F C Hibben: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Alaskan Muck on the Kokolik River: US Geological Survey, Public Domain

- Alaskan Aeolian Deposits: © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Fair Use

- Paul V Heinrich: © 2017 Academia, Fair Use

- Arctic Muck in the Canadian Territory of Yukon: © Brent Aloway, Edmonton Journal, Fair Use

- Troy L Péwé: © 2006 The Arizona Geological Survey, Fair Use

- Stratigraphy of Quaternary Deposits in the Fairbanks Area: US Geological Survey, Public Domain

- Projectile Points from the Alaskan Muck: © Froelich Rainey, Fair Use

- Projectile Points: Alaskan Muck, Yuma Point, Inuit Point: Adapted from © 1940 Froelich Rainey, © 1968 John Witthoft, Wikimedia Commons, Fair Use

- Robert M Thorson: © Alex Ashlock, Fair Use

- Glaciated and Unglaciated Alaska: © 2017 Alaska Humanities Forum, Fair Use

good post. It is lake but it is worth reading. Congratulations ... It will be a pleasure to follow you and I hope you follow me.

Thank you. I may have to brush up on my Spanish, though.

I love this kind of material.

Thank you.