Vampires, Comics and King; How Stephen King and E.C. Comics Gave Vampires Back their Bite

Vampires, Comics and King

How Stephen King and E.C. Comics Gave Vampires Back their Bite

Eleanor Sciolistein

..................................................................................................................................................................................................

In Alan Moore’s classic graphic novel The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (not to be mentioned in the same breath as the nauseating movie version starring Sean Connery) there are no vampires.

What there are, however, are fantastic hints at how vampires, the kind of vampires that actually instil fear, should be portrayed. There is also a clue as to where the real spirit of the undead survived, untouched by Hollywood for decades.

In Moore’s graphic novel, which brings together literary characters from a number of Victorian classics, Mina Harker, star of (and survivor of) Dracula, is a prominent character. Throughout the series she wears a scarf around her neck which we find out in due course, is to conceal the scarring she received during her encounters with Dracula. The scars are horrific. More akin to the marks left by an an attack by an animal than a human, which of course, is the beauty of it.

Forget any image you may have of twin pin pricks delicately placed on a naked neck, these are marks of savagery. Without explicitly appearing in the text at all, Dracula and vampires generally are given a splash of characterisation by Moore that is too often downplayed. And no, it isn’t sparkling in the sunlight like a fucking unicorn, ala Twilight. The implied ferocity of the attacks by Moore’s Dracula, drag the vampire back to a much earlier portrayal. A portrayal that is far more brutal and crucially more animalistic than many modern interpretations.

It is a portrayal that is older than film, that was sanitised by Hollywood, and all but extinguished by spoof and parody, but also one which persisted lurking in the pages of comic books for years. It is also a portrayal which owes it resurrection in modern film and mainstream literature to an early novel by the ‘king’ of horror, Stephen King (pun entirely and unashamedly intended).

Ask most people to name a vampire and they will immediately say Dracula, (If they even mention Robert Pattinson feel free to beat them to death with the heaviest copy of Dracula you can find). Ask most people to draw a vampire and you are likely to get something that resembles the horrible offspring resulting from a nightmarish menage a trois between Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee and the Count from Sesame Street (God help us all).

What is interesting about this, is that although the commonly held image of a vampire is based upon the archetypical ‘Dracula’ as portrayed by Hollywood -all pointy canines, upturned collar and nonspecific Eastern European accent - these images are a world away from the Dracula of the original novel.

If we look back at the descriptions of the count in Stoker’s masterpiece, the outline given is one which is decidedly animalistic and feral. The face is described as aquiline, the teeth are pointed and rodent like, the hair is profuse and bushy and the ears are also pointed, later he is compared to a lizard. Animal descriptions for something less than, or at least other than, human.

It seems that the older and closer in time to the folkloric source material the vision of the vampire in literature or film is, the more like the terrifying, pestilent and crucially ‘animal like’ creature that haunted folklore it becomes, with even the character of Geraldine in Coleridge’s very early vampire work Christabel having serpentine eyes.

It is no coincidence that amongst early on screen visions, it is the first (all be it, unofficial ) adaptation of Dracula, FW Murnau’s Nosferatu, which shows the vampire to be at its most repulsively animal like. Max Schrek’s Count Orlock is strikingly abhorrent, and retains many of the more bestial features described in the novel and lost by the time Bela Lugosi’s Eastern European lothario slithered onto the screen in 1930.

This is not to say that the notion of vampires possessing an alluring magnetism is to be overlooked. In all of the versions mentioned above the vampire is capable of entrancing and enticing its victims, though crucially, although they retain this power of attraction, they do not become the suave lounge lizards or dough eyed teen heart throbs of later screen renderings.

Luckily, whilst Hollywood did its best to humanise the inhuman and equate the undead with the unblemished, this earlier, more visceral and physically threatening vision of the vampire was maintained, not on screen or (with a few exceptions) in novels or short stories, but in the pages of comic books.

As a medium that mixes narrative with visual illustration, sequential art has always been the perfect place for horror and whilst some would argue that it might somewhat diminish the power of imagination or suggestion that makes the greatest horror novels so extraordinary, what they lack in subtlety they make up for with in your face graphic representations of nightmares and monsters.

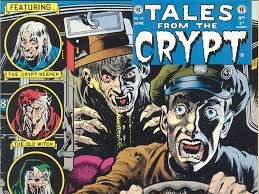

Before vampires and werewolves were banned outright under the comics code, titles such as Tales from the Crypt, Tales from The Vault and Vault of Horror with art from the legendary Graham Ingles, and published by the notorious EC comics, presented vampires with all the predatory physicality that made them so scary in the first place.

It was in the pages of these comics that a young Stephen King, who by the time he encountered them had already read and digested Stoker’s classic, found the vision of vampires that would influence his bloodsuckers in Salem’s Lot. In his introduction to one edition of the novel he speaks of a desire to “combine the overlord vampire myth of Stoker’s Dracula with the naturalistic fiction of Frank Norriss and the EC comics I’d loved as a child”. But what was it about the vampires King found in those old comic books that he wanted to use? Nothing less than their tangible viscerality. These were not movie pin ups, they were solid, breathing, monsters.

In his introduction to another edition, King recollects finding a “New breed” of vampires in the EC comics that were “Cruder” and more “Physically monstrous” than Stoker’s fiendish aristocrat.He goes on to explain how the vampires that frequented these pages were prone to “tearing and ripping and shredding”, worlds away from the besuited bloodsuckers of the big screen he recalls that these vampires “didn’t just scare me, they fucking terrified me!” and so they should.

When in their natural state, the creatures that emerged from King’s amalgam of Dracula and this more brutish, subhuman, EC vision of the vampire are worlds away from the sanitised ‘halloween costume’ villains that clogged up Hollywood’s depiction of the vampire for so long.

In recent years this trend has been bucked and whilst we do have to endure the whole ‘vampires as adolescent pinups’ nonsense, there are plenty of films, comics and novels that present a picture of vampires as the frightening hunters of humanity that they were always meant to be, a picture, which in no small part, owes its reintroduction into popular culture to some dusty old EC comics and the pen of Stephen King.

Posted from my blog with SteemPress : https://sinfullyvin.com/vampires-comics-and-king-how-stephen-king-and-e-c-comics-gave-vampires-back-their-bite/