Czech Gallery - A Roaming Prague Homage to Kafka Part I

July is Franz Kafka’s birth month, and this post is dedicated to his memory.

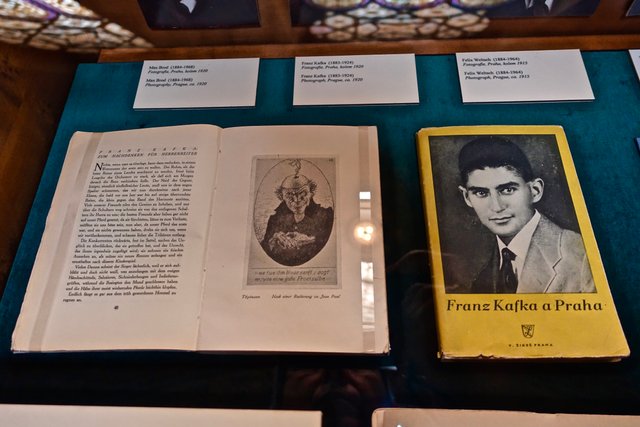

He was born in Prague on July 3rd 1883. He is the one who put Prague on my map back when I was studying German literature at university. So when I started going through my bucket list of places to visit, of course Prague was among the top destinations. Since my student days, I have developed other interests in parallel, so when came the time to plan my trip, Kafka was competing with other activities. Nevertheless, when I finally got to Prague, I din’t have to look for Kafka. He, or rather his spirit and his memory just found me, starting with the beautiful house on Staroměstské náměstí right by Old Town Square that I passed almost every day during my stay.

The dum U Minuty or house “At the Minute” has been standing there since the sixteenth century. Over the years, you can imagine that it has undergone a few transformations in terms of appearance and usage. The Kafka family lived there from 1889 to 1896. It was a nondescript house, save for the eighteenth century lion in the corner that winks at earlier times when the house was a pharmacy and was called “At the White Lion”. In the early 1900’s it was slated for demolition but it got a reprieve when sgraffito was found on the neighboring house. In 1919 repairs revealed the exquisite seventeenth century sgraffito decorations that we can admire today on the façade. Sgraffito, from the Italian “to scratch” is a technique that was used on many Czech Renaissance buildings consisting in applying several layers of plaster in different colors then through the top layer to reveal the underlying layer in a contrasting color. Despite its proximity to the astronomical clock, the name of the house has nothing to do with time-keeping. Instead it refers to the tobacco shop on the premises where tobacco was sold to customers in small quantities.

Franz’s father Hermann Kafka was originally from a Czech village in southern Bohemia where his own father was a shochet, also spelled shohet (I had to look it up. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary it is a person officially licensed by rabbinic authority as slaughterer of animals and poultry for use as food in accordance with Jewish laws). In the Jewish tradition, Franz Kafka’s barmiztvah was held in the Old-New (Altneuschul) Synagogue. When it was built in the last third of the thirteenth century and was called the Neu (new in English) Schul, however as other synagogues were built they obviously were newer and Alt (old) was, hence its name. Beside being the oldest active synagogue in Europe it has a couple of other peculiarities: it is the oldest surviving synagogue with a twin-nave design, and the Golem (a creature fashioned by Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel out of clay from the banks of the Vltava river) is said to have hidden in its roof. Incidentally, the fragment of a story of a rabbi working on a clay man was found in Kafka’s diaries, but as far as the rest of his work is concerned, if one cannot say that Kafka is an explicitly Jewish writer, cultural influences do come through. It is interesting to note that the Jewish ghetto of Prague was razed in 1897 and one can surmise that it would have been a topic of conversation around the dinner table of a domineering head of household.

Hermann Kafka was a driven, upwardly mobile man. German, the upwardly mobile language was spoken at home and at school, and was the language that Franz Kafka would use to write. Franz had the benefit of an excellent education. He attended the Altstadter Gymnasium located in the beautiful eighteenth century Kinský Palace next to the Stone Bell Tower on the east side of Old Town Square. From there he went on to the Deutsche Karl-Ferdinands-Universität of Prague where he earned his Juris Doctor 1906. At the same time, Hermann Kafka had a haberdashery store on the ground floor of that same building. Nowadays the Kinský Palace houses the Asian Collection of the National Gallery (Národní galerie v Praze). https://www.ngprague.cz/en/

For all these social benefits, there is the other side of the coin. In his famous letter to his father Kafka writes: “There is only one episode in the early years of which I have a direct memory. You may remember it, too. One night I kept on whimpering for water, not, I am certain, because I was thirsty, but probably partly to be annoying, partly to amuse myself. After several vigorous threats had failed to have any effect, you took me out of bed, carried me out onto the pavlatche, and left me there alone for a while in my nightshirt, outside the shut door. I am not going to say that this was wrong—perhaps there was really no other way of getting peace and quiet that night—but I mention it as typical of your

methods of bringing up a child and their effect on me. I dare say I was quite obedient afterward at that period, but it did me inner harm. What was for me a matter of course, that senseless asking for water, and then the extraordinary terror of being carried outside were two things that I, my nature being what it was, could never properly connect with each other.

Even years afterward I suffered from the tormenting fancy that the huge man, my father, the ultimate authority, would come almost for no reason at all and take me out of bed in the night and carry me out onto the pavlatche, and that consequently I meant absolutely nothing as far as he was concerned.”

(By the way, a pavlatche is (a sort of balcony running along the inside courtyard of the house). You can find the entire letter here: http://www.heavysideindustries.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Franz-Kafka-Letter-to-his-father1.pdf

Below is a facsimile that I found on http://www.escapeintolife.com/literature-essay/kafkas-letter-to-his-father/

Needless to say, Franz Kafka had some serious father issues and that impacted the themes and the characters of his stories. Combine deep psychological scars, a fragile health and an artistic temperament, and you will understand that Kafka’s work evolves in a quasi-nightmarish world of incomprehension, authority, fear, and malaise. It is hard to read. Hard not in terms of difficult. Indeed, the language is incisive and precise (perhaps one has his training as a lawyer to thank) which adds to the surgical cruelty of his reality. No, it is hard to read without feeling ill at ease oneself.

End of Part One of Two

.jpg)

Hello there, you have recieved an upvote/invitation from Trojan Wall.

We are a new group of authors who support each other.

Currently we are searching for new members. If you are interested in joining us you can read the guidelines on our posts.

If you have any questions feel free to ask on our discord server: https://discord.gg/4YXdZVN

Stay strong.

Thank you very much, I appreciate the upvote and invitation. You have piqued my interest and I'll check out Trojan Wall in more depth over the weekend as my work week is pretty intense.

Very nice post. I would love to visit Prague one day.

Followed.

Cheers! @Rebele93

Thank you very much. Prague is a beautiful city. An intense week there and I didn't get to see everything I wanted to see. Beautiful architecture, centuries of fascinating history, culture-rich (whether it be music or literature or visual arts), and from what I hear some pretty serious beer.