Of an Age With Rome (featuring Vasily Peskov as author)

The structures are fantastic. I had the strangest feeling when I first saw them, a feeling that I had known them all my life.

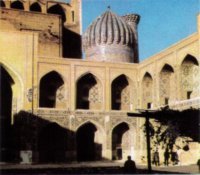

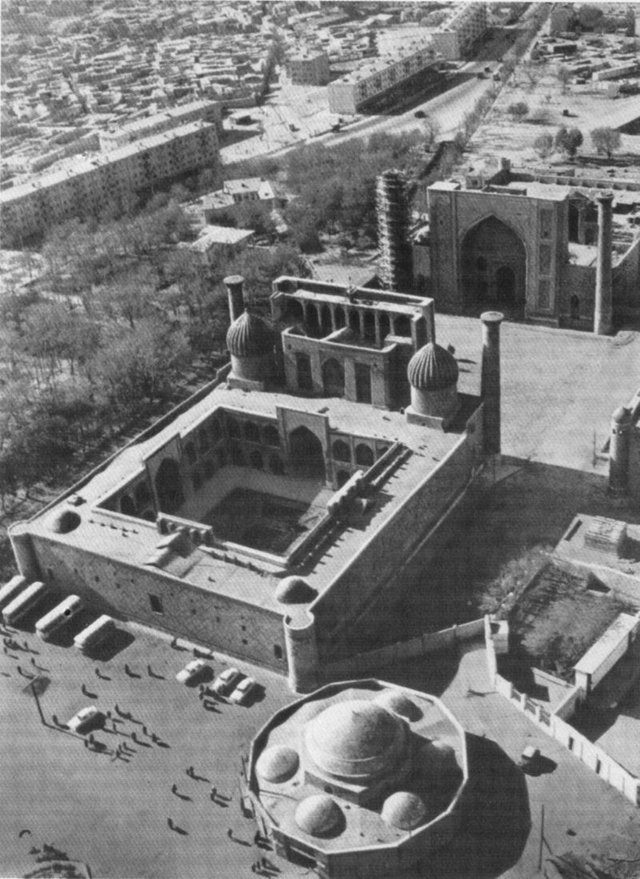

We flew over the Registan on a bright, sunny day. The turquoise buildings resembled ships that had sailed in from some unknown place and were now moored among the little houses and busy automobiles. Though the crews had long since vanished, their ships remained. Here were the strange decks, the stacks and the blue covering of the sides. The ancient blue flotilla had come to rest on Samarkand's central square.

Visitors gather here every morning. It is not unusual to hear many foreign tongues and learn that the visitors have come from Paris, London or Prague, or from the Soviet cities of Rostov, Semipalatinsk and Gomel. People thirst for knowledge everywhere and find joy in gazing upon these blue ships from the past.

This square, which is known as the Registan, is the first place a visitor seeks out in Samarkand. This is where he begins his tour of the wondrous city.

There is a teahouse in a garden off the square. Two wooden posts adorned by carvings and the marks of wood-borers support the roof of this ancient eating-house. Lamb is roasted on skewers outside on the pavement, while pea soup bubbles in a huge kettle. The fragrant blue smoke of a charcoal fire drifts off among the trees. Farther on, beyond the modern box-like houses, is the old residential section where the flat-roofed houses seem stuck together so that one might actually cross the city by going from roof to roof. The winding streets have many lanes and dead ends, all of which confuse one's sense of direction.

At a distance of about a thirty minutes' walk from the square you suddenly catch sight of a huge blue cupola above the treetops. Words once read are now recalled: "If the sky disappears the Gur-Emir Cupola will take its place."

The remains of the famous Timur, who regarded Samarkand as the one capital of the world, are buried beneath the cupola. Everything possible was done to embellish the city. Skilled craftsmen, both native-born and prisoners-of-war, raised its arches, minarets and cupolas, none of which have lost an iota of their heavenly blue in all the succeeding centuries. Timur, barbarian among barbarians, was a wise ruler at home, as evidenced by his laws and state system. He had the Gur-Emir Cupola built as a mausoleum for his grandson who died during one of his campaigns. However, there was room enough inside for the lame conqueror as well. His remains rest under a block of nephrite. Shortly before the outbreak of World War II a group of archeologists raised the block, revealing the coffin of mulberry wood underneath. There is an electric light in the underground vault over Timur's grave now.

Sparrows raised a din on top of the cupola, while Uzbek children played hide-and-seek among the stones and niches of the tomb. I stood in the archway, lost in thought and suddenly heard someone clear his throat and say, "Timur was no fool." The man who had struck up the conversation was a pleasing old Uzbek.

I agreed that Timur was no fool.

"He knew where to build his capital," the old man said and then offered to take me sightseeing and tell me things that were not to be found in the guidebook.

Since I did not have a guidebook, I could not manage an on-the-spot check of what there was and was not about Samarkand. When I did check, however, I found that my volunteer guide had faithfully recounted whatever was to be found on its pages. Still, I am grateful to him, for his slow and solemn story included dramatic sighs, exclamations and whispers whenever he spoke of something especially significant. I learned that the population of Samarkand now stands at 250,000 and that the city is one of the most ancient in the world, a contemporary of Rome, Athens and Babylon. Tashkent is the comparatively recent capital of the Uzbek Republic, while Samarkand was its original capital. I learned how much new housing was going up in the city, how much wine, tea, chemical fertilizers, movie cameras and spare parts for farm machinery it produces. The old man kept comparing these figures with those of the prewar years and I was amazed at the difference. I even suspected him of exaggeration, but then saw that he had been right. He apparently did not want to be at odds .with the guidebook.

One should always explore Samarkand on foot. Even if you do not know your way around you will sooner or later come out to the ruins which resemble yellow cliffs from afar.

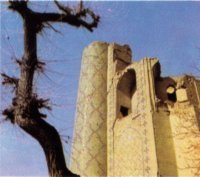

The ruins of Bibi-Hanum.

"That's the Bibi-Hanum," the old man said. He fell silent. I, too, gazed at the ruins, resurrecting in my mind's eye the contours of the great structure. The old man then went on to tell me the legend I had read before: "Timur and his armies were on the march. His wife, Bibi-Hanum, decided she would have a mosque built, the likes of which were not to be found in Samarkand. The architect fell in love with her and yearned for his reward, a kiss. When Timur returned his rage was boundless. But something had gone wrong. No one knows whether it was due to haste or miscalculation. Whatever it was, the mosque began to crumble."

However, the ruins draw the visitor as no other ancient site in Samarkand does. It seems that if a bird as much as grazes the wall with its wing it will all come crashing down. Birds swoop by, the crimson sunset is reflected in the glazed tiles and the contorted, branchless trunks of the mulberry trees appear stark and black.

"When Timur returned the architect rose up from that minaret on wings and flew off to Iran," the old man whispered.

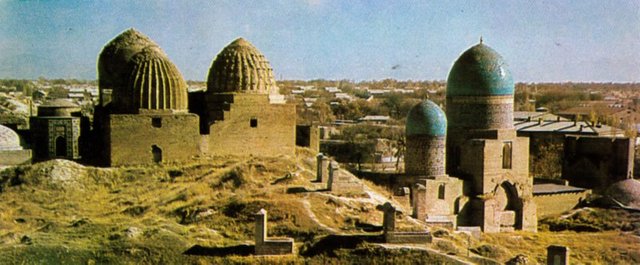

What else should one see during a two- or three-day visit? You will certainly be shown the majestic Hazret Shah-Zindeh, "the city of the dead". It consists of a long row of mausoleums, some with tiled cupolas and some with untiled ones that resemble shaved heads.There are intricate designs and vaulted arches. The sound of one's steps is muted here. All this was built with a vision of Allah and a life after death. However, yet another architectural monument of the same period is certainly as noteworthy as all the cupolas of the "dead city". Ulugbek, Timur's favorite grandson, was perhaps the first in Asia to doubt the existence of Allah. He did not declare this doubt openly to his subjects, but the observatory he had built on the nearby hills and the very outlook of this ruler of Samarkand made the fanatical Moslems plot his murder. The details of this drama were revealed to us five centuries later. The stone arch that goes deep underground was part of an ancient astronomical instrument. There are numbers on the stone. One can visualize the bearded Ulugbek working in the vault at night, searching for the truth.

One of the many ancient

structures.

The ancient buildings of Samarkand are like islands in the city. If you rise a bit above any street you will see the turquoise cupolas floating in the blue haze. The new Opera and Ballet Theatre is another island of stone and glass that fits in well with the surrounding monuments of the past.

The blocks of standard, modern housing will not be of interest to the visitor, for he has seen similar box-like houses in his own town, but a local inhabitant who lives in an old building with few modern facilities is pleased at the ever-increasing number of new houses.

There is a university here, three colleges and about two dozen secondary technical schools, as well as fifty factories and plants. Strangely, one never catches a whiff of industrial fumes. The smells I do recall are those of freshly-baked flat-cakes, roast lamb and burning leaves in bonfires. One does not feel annoyed at losing one's way here in the evening, for it is a pleasure to wander up and down the crooked lanes of the Old City. There are trolley-buses in Samarkand and a single-route streetcar. As we rode along we overtook a crowd of students, a village cart with wheels as high as a man and a small flock of sheep destined to become shashlyk that very day. We passed a man carrying two roosters by the legs, their heads dangling. It was a Sunday and all the roads from the outlying settlements led to the bazaar in Samarkand. The settlements hereabouts have grand names: Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad. They were named thus in the days of the vainglorious Timur.

Our tour of the city ended at the bazaar. It was evening. "What would you say Samarkand is most famous for?" I asked my guide.

The old man did not reply at once. Finally, he said, "For its flatcakes."

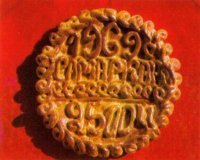

This flatcake can be eaten or

presented as a souvenir.

I smiled, taking this as a joke and a hint, but he was quite serious. He then told me a long tale about flatcakes which included a story about Timur taking a local baker along on his campaigns and a funny story about a British tourist who took two dozen flatcakes home as gifts. The secret of the ancient recipe for these glorious flatcakes has been preserved, to the joy of us all.

We found a comfortable spot near a pile of melons and there we shared a flatcake and some shrivelled grapes that were half-raisins. I tried to recall when I had tasted bread that was better and decided that perhaps this was during the war, when every bite of bread was wonderful.

Before bidding my guide farewell I bought a flatcake decorated with baked, golden-brown lettering. The legend, in Russian and Uzbek, read: "Greetings from Samarkand".

The streetcar rumbled along. A group of students were strolling by with their arms around each other. Here and there piles of old leaves were smoking. A thousand years ago the inhabitants had probably burned old leaves in autumn just like this. The fragrant smell wafted over the city, bringing back old memories.

Thanks for the information about Samarkand. Can you give me a bit more information about this city. Where is it located? Why did different nations gathered there in the past? Was it a big trading city?

If you are interested in history, see my history ARTICLE for today.