Crushing on Buenos Aires: Remote Year Month 1

Four weeks might not be long enough to fall in love with a city, but it’s certainly enough to have a hard crush on it.

Like many of the best relationships, my introduction to Buenos Aires, Argentina wasn’t typical. Fourteen hours after I arrived, I fell off a curb in front of my apartment building in Palermo and broke my jaw in two places. Instead of savouring barbequed meat and stuffed pastries, I slurped nutrition through a straw and planned sightseeing around the availability of yogurt drinks.

As odd as my month was, it was kind of fitting. In between medical appointments, I discovered that Buenos Aires is a city of contrasts in a country with a complicated history. The sidewalk stones are cracked and uneven but the streets are dotted with upscale restaurants and modern boutiques. Crumbled building facades are covered by colourful street art that makes the streets vibrant. Dogs walk the streets without leashes but never wander into traffic. Trees line the streets and they’re frequently yarn bombed. The city is imperfect, but it’s alive — a place I could imagine living, even if there are a few things that take some getting used to.

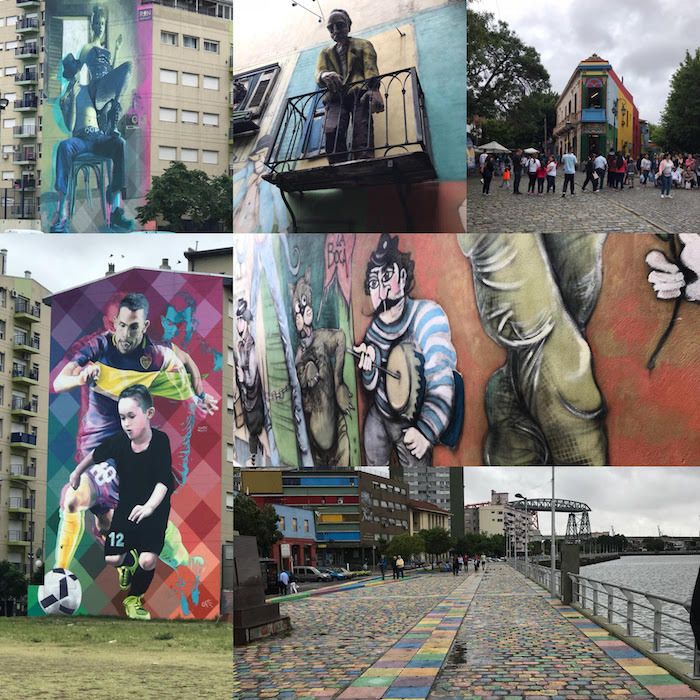

Street art in Buenos Aires by artist Boxi Trixi.

Buenos Aires, and all of Argentina, operates on its own schedule. Everything starts later and takes longer than North Americans expect, and efficiency isn’t popular. Even though I knew this ahead of time, it was hard not to get frustrated. But the locals also experience everything they do instead of just going through the motions. Standing in line or waiting at a restaurant for a meal gave me time to look around and see the expressions on peoples’ faces as they talked — their wide eyes, raised eyebrows, and open mouths — and elevated volumes. Passion infused every conversation, particularly if the topic was football. Remote Year’s local experience manager, Juli, put it this way: “Argentinians are very opinionated and we’re not afraid to share.”

To really understand what Juli meant, you need to appreciate Argentina’s modern history.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Argentina was the world’s seventh largest economy. The country attracted European immigrants who wanted to build a better life or escape from their legal troubles at home. As the city grew, its wealth wasn’t distributed evenly. Economic crises were common, and inflation and violence frequently spiralled out of control. Between 1930 and 1984, there were five military dictatorships. The last one was the longest and most violent. The wounds are still fresh, and it was hard for me to wrap my head around the fact that it all happened while I was watching Saturday morning cartoons while my parents slept.

Between 1976 and 1983, an estimated 30,000 people in Argentina went missing — presumed killed by the military junta that took control of Argentina’s government. It was illegal for people to gather in groups of four or more and citizens could be detained without cause. On a visit to Parque de la Memoria (Memory Park), which commemorates this dark history with a series of art installations and memorial walls, our tour guide described how difficult it still is for Argentinians to talk about what happened. He also warned us to apply sunscreen and drink lots of water. The park, which sits on the edge of the Rio de la Plata estuary, has almost no shade. “It’s meant to be uncomfortable,” he said.

As a Canadian, I find Argentina’s history fascinating because Canada’s own history and collective identity are so different. Canada’s existence as a country didn’t come from revolution; it came from meetings among European settlers who decided it should happen. What we commonly think of as war hasn’t been fought on Canadian soil in 200 years, and our defining national moments — as recorded in history books and taught in school — are either homegrown successes or sacrifices abroad. All of this makes it hard to grasp what makes Canadian tick, but Argentinians have a collective experience that makes up who they are.

Juli meant that Argentinians speak their minds because they can, and because they know what it’s like when you can’t.

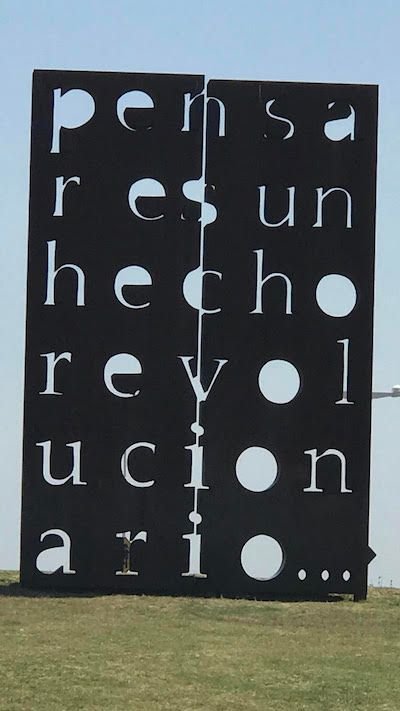

An art installation at Parque de la Memoria: “To Think Is a Revolutionary Act.”

Now, porteños (the nickname given to people from Buenos Aires) aren’t shy about celebrating. The party scene in Buenos Aires is legendary and it’s no exaggeration when they say that nightlife starts late. A 10:00 p.m. dinner reservation is normal and most nightclubs don’t open until well past 11:00 p.m. This is well past my own bedtime, but there was a blissful exception to the late-night hoopla that gave me a taste of what it’s like to party with locals.

La Bomba de Tiempo is an improvised percussion performance by a 20-person ensemble that has been performing every Monday at 7:00 p.m. for the last 12 years. The venue serves only one kind of beer (which comes only in one-litre servings) and a limited selection of mixed drinks, including fernet and coke — an Argentine staple that is an acquired taste.

But the point of La Bomba isn’t to drink. It’s a non-stop, three-hour dance party led by rotating conductors who each use signals to tell the band what to do next. The standing-room-only dance floor felt like a giant mosh pit, and I absorbed every beat. Drinking is for the after-party, which happens at a nightclub about eight blocks away. To get there, the band leads a procession through the streets, where you can buy more beer from pop-up vendors. Even if after-parties aren’t your thing (I chose to skip it), the street parade is still ridiculously fun and the whole experience is 100% pure Buenos Aires.

Like most big cities, Buenos Aires is still a mix of rich and poor. On a bicycle tour that started in the city’s San Telmo neighbourhood, we were flanked by the richest and poorest areas of Buenos Aires. On one side, there was Puerto Maderas, which was originally built as a port to accommodate large cargo ships but was redeveloped in the 1990s, inspired by international neighbourhoods like the Docklands in London. Now it’s a luxury enclave with its own dedicated police force. Just a few blocks away in La Boca, people learned to take care of themselves.

La Boca is the home of tango — not the elegant, passionate tango that’s immortalized in the movies, but the gritty, violent tango of the 1880s in which men “danced” with other men to prove their strength to women. La Boca is also home to some of Latin America’s most accomplished football players, in large part because playing football was the only thing that kids could do growing up. It’s gritty and rough, but the people have character and they are proud. Today, famous footballers are returning to their communities to give back, and local street artists are breathing colour and life into drab grey walls and making the neighbourhood something to be proud of. At the same time, you still need to mind your wallet and your cell phone, especially if you look like a tourist.

Street art in La Boca shows the community’s pride.

My favourite thing about Buenos Aires, though, is its love affair with books. The city has more bookstores per capita than any other city in the world. Streets like Avenida Corrientes and Avenida Sante Fe are packed with small, independent shops, sometimes side by side, each with their own specialities and quirks. They’re not even books I can read — despite the population of immigrants and ex-pats, the books are almost exclusively in Spanish.

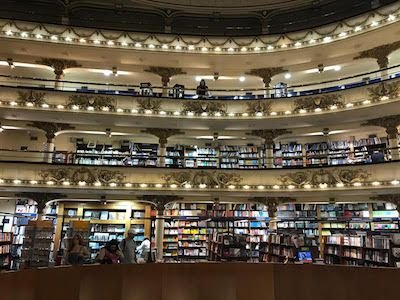

El Ateneo Grand Splendid, considered one of the most beautiful bookstores in world, has just two narrow shelves dedicated to books in English, and there is only one small chain of stores that exclusively sells English-language material. With a rich history of Latin American literature and a healthy appetite for Spanish-language translations of popular American titles, Buenos Aires doesn’t need books in English.

El Ateneo Grand Splendid was an opera house before being turned into a bookstore.

More than the street art and the bookstores, though, what I will remember most about my time in Buenos Aires is how it shaped my relationship with my community. Breaking my jaw in a country where I don’t speak the language meant that I had to lean on other people — a lot. My entire Remote Year community surrounded me with support. They cooked soup, recommended smoothie shops, and took me blender shopping. They kept me company, and they cared. I went to the hospital 13 times. Every time, our Remote Year city manager, Santiago, came with me to translate. I never seriously entertained the idea of going home for treatment because I was so well looked after where I was.

Even though our Remote Year group moved on after four weeks, a little piece of my heart is still in Buenos Aires. Even if I can’t read all the books it has to offer, I can’t help but adore a city that made me open my eyes and my heart. I also can’t help but wonder how many times over the next year I’ll fall in love with a city, but in Remote Year terms, they say the first one is always special. Thank you for that, Buenos Aires. See you soon.

Next stop: Córdoba, Argentina.

This post was first published on Medium.com/@kaarina on March 6, 2018. Steemit will become my first publishing platform for new posts once I have you all caught up.