The Age of Deep Sea Mining Begins...But At What Cost?

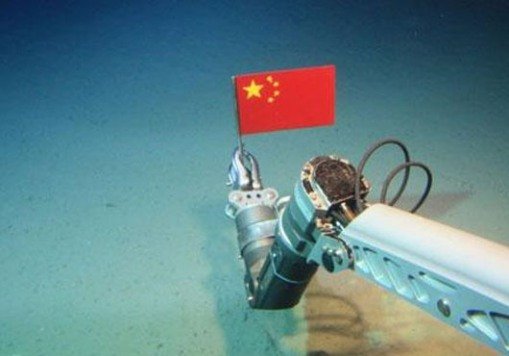

Much was made of James Cameron’s history making return to the Challenger Deep back in May of 2012, yet one year prior on a sunny day in July Chinese marine engineers witnessed the descent of the Jiaolong submersible to a depth of 5,000 meters, with a 7,000 meter test.

While it largely escaped the public’s notice, the fact that the Jiaolong placed a small Chinese flag on the ocean floor raised many eyebrows among US politicians and industrialists. A similar stunt played out in 2007 beneath the arctic ice, with a resurgent Russia laying claim to the mineral and petrochemical resources known to exist there in abundant deposits.

China’s nationalized deep sea mining organization has since been issued the necessary permits to mine the South Indian Ridge, joining corporate entities like Nautilus Minerals and Neptune Minerals in a new gold rush, four miles down to the frigid black floor of the ocean. This will be carried out from a manned deep sea habitat supporting a crew of 12 initially, though it will later be expanded to host 33.

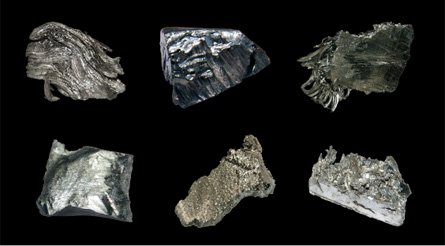

In each case hydrothermal vents, rare earth mud deposits and other sites of interest are first surveyed by manned deep sea submersibles before a refinery vessel (or a deep sea submersible operating at depth) deploys a robotic mining vehicle to the mining site.

The ones in use today are quadrupedal or tracked and use a bucket wheel excavator to carve up the vents, essentially deep sea volcanoes, and a suction hose to transport the ground up mineral slurry to the surface vessel for processing.

Amidst this clamor for oceanic resources, scientific voices have cried out in protest. Hydrothermal vents represent some of the least understood and most scientifically valuable research sites in the ocean. As the abyssal plain alone comprises a landmass larger than every combined continent, the vast majority remains unexplored.

Today’s submersibles, being purely battery powered (internal combustion engines will not function in water) spend most of their time in descent or ascent, moving very little horizontally. Consequently only 10% or so of the ocean bed has been explored and new species are discovered in every dive, many around vents.

Because vent species rely on chemicals emitted by them to survive and cannot traverse the huge distances between them, hydrothermal vents act as a sort of deep sea galapagos islands, with evolutionarily distinct populations living around each one.

Aside from the obvious conflict of interests that results when a mining company must destroy a completely unique ecosystem in order to mine its volcanically deposited, high grade precious metals, there’s also questions concerning the sediment plume.

The bucketwheel excavation method would release a vast column of sediment that may or may not disrupt the day to day survival needs of local species. This has led to local protests against deep sea mining projects, including the Indigenous People of Bismark and Solomon Seas who have petitioned the government of Papua, New Guinea to suspend mining altogether.

As the indigenous fishermen of those regions rely in large part on seafood for most of the protein in their diet and on the health of fish stocks for their livelihood, the potential impact of deep sea mining on those fish stocks could be devastating for them.

This may well be where the Chinese government's ambitious approach shines. Putting human beings on-site to operate the machines with direct line of sight may make possible more precise, careful mineral extraction with less resulting sediment than operating the robots blindly, or over video monitors.

The great irony here is that the metals everybody's after are needed most of all for stuff like solar panels, electric cars and other environmentally friendly technologies. Should we sacrifice the health of the ocean for the health of the atmosphere? Is that even possible when the two are so intimately related and interactive?

Realization of this has driven many key players like Tesla to develop electric motors free of the rare earth minerals that deep sea mining corporations aim to extract. There will continue to be strong demand in other markets though, as those metals are used in a wide variety of consumer electronics.

Can we go into the ocean and harvest its wealth in an environmentally benign way, for the good of the surface world? Or will we only repeat the environmental blunders in the ocean that we already have on land? Perhaps the best answer is the apocryphal quotation, purported to be a Chinese curse: "May you live in interesting times".

We do indeed live in interesting times, but it remains to be seen which of the two interpretations of 'interesting' will best describe the future we are moving into.

I love Deep Sea Pepe!

In the deep there are no feels, only eels