Negative effect of teacher training and first year of teaching

How my training year (PGCE) and my first school affected my teaching negatively

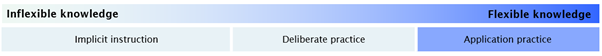

I think all science teachers have same end goal for their students (whether they are self-proclaimed progressive or traditional in their style): flexible knowledge. Knowledge that is easily applied to contexts other than the one they originally learnt the concept.

When I first started teaching, it was the era of showing “progress in 20 minutes” and or at the very minimum you had to provide evidence that progress was made by the end of the lesson. At the same time differentiation by different worksheets was big and so were graded lessons. This environment shaped my teaching and probably that of nearly everyone that trained around that time.

The lesson was the unit of learning. Everything should be covered and observable in one lesson, if it wasn’t observable there and then, it would never happen. I had a “fantastic and amazing” lesson downgraded to satisfactory because the evidence of progress was not produced on paper within that lesson. Differentiation was hot and we had to think about the individual needs of all the students whilst also flying them through a “progress in 20 minutes” system. Easier worksheets and simpler questions were the result as you had no time to get the slower students up to speed in such a short amount of time. As such, almost all my lessons followed a similar pattern which became routine:

(Skip to the bottom if you just want to see what I do now)

Twitter had me interested in SOLO taxonomy, thanks to David Didau’s blog posts (@DavidDidau), and it fitted perfectly into my will to get my students to apply their knowledge. I would condense the stages of the taxonomy into every single lesson, expecting students to go from learning knowledge to application of that knowledge to new contexts within 50 minutes. The students struggled, but struggle was fashionable, and I believed it was good for learning. Eventually I produced a mix of application questions and simple knowledge recall questions (all from the content of that one lesson) so that all students had access to at least some questions (under the popular guise of giving the students the choice of what questions they could answer). Differentiation by access you could say; despite wanting flexible knowledge for all my students, I was only offering application of knowledge practice to the students with the highest working memory capacity, because the slower students couldn’t retain the lesson’s knowledge and apply it without suffering from cognitive overload. Not only that, but hardly any students would retain what we learnt just a few weeks ago, but I was blinded by the rush to flexible knowledge in the time frame of one lesson; this was what we were measured on, and this is what was important for passing the PGCE (training year), passing my NQT year (first year as a teacher,) and passing observations with senior management.

Over the last few years, thanks to twitter and the amazing books and blog posts that are produced by the active members there I have escaped this tyranny of teaching to a measurement, and now focus entirely on teaching for long-term learning.

Click here to see other posts in this series:

The background context (This page)

Part 1 of how I sequence my lessons (time and interleaving)

Part 2 of how I sequence my lessons (lesson types in the sequence)

Part 3 of how I sequence my lessons (Guided application and linking knowledge)

Part 4 of how I sequence my lessons (Application of knowledge)

I have to give a shout-out to the authors and bloggers who have made the biggest influence on my thinking: David Didau @DavidDidau, Greg Ashman @greg_ashman, Craig Barton @mrbartonmaths, Adam Boxer @adamboxer1, Daniel Willingham @DTWillingham, Dylan William @dylanwiliam.