AprilTTRPGMaker Day 13: Biggest Influences

The question for day 13 of #AprilTTRPGMaker is about influences. I think everything influences us in some way. I can point to some obvious influences, like J.R.R. Tolkien or the game designs and theory ideas of Vincent Baker (although not always influential in an “I want to follow them sense), I'm not good at extracting ingredients back out of the stew of my mind. But probably the thing that influences me that's somewhat unique among people participating in the hashtag was my career in the microprocessor industry (I worked at Intel), so I'll talk about that a bit.

(Pentium 4 die photo originally from Intel)

Computer Architecture

My job primarily focused on understanding the memory/bus architecture/microarchitecture of multiprocessor-capable microprocessors. That meant I had a lot of expertise in understanding memory ordering and cache coherency. I think there are a lot of analogies there to how, when we play an RPG, we all have individual imaginary situations happening in our heads that need to be kept somewhat “in sync”. The Forge had a concept of a “Shared Imagined Space” as an idea that what is spoken aloud is the canonical version of the game state, but in my view that's a vain attempt as simplifying a complicated process. There's rarely a canonical “current state of memory” stored anywhere in a multiprocessing computer system – you can figure out what different agents would say if asked, but if you want to truly understand how the system operates you have to appreciate the parallelism and how the agents interact, not assume that the external stuff is more important (it's more easily visible, of course, and all interactions will entail some external visibility, but a lot of the important action is happening inside).

A lot of the ways I think about games and about how people think involve metaphors from this part of my life. For example, I think it's often useful to think in terms of inputs and outputs. When a processor is connected to a bus there's often entirely different hardware that handles transactions from us going out onto the bus or transactions from other agents that might need to come in to us. In a game I think it's often useful to think about what people are saying and what people are listening for as two different-yet-connected mechanisms rather than just treating it as “the fiction”. And there's also the interesting case where you use your own output as an input, such as when you “self-snoop” your own cache, or when the process of articulating something out loud helps you clarify ideas or characterization you didn't know you had in you.

As a more specific example, many of the complex structures in a microprocessor use what's called a Content-addressable memory or CAM. What happens when you want to see if an address is stored in the cache is that you present the address you're interested in to the cache interface, and the cache does a “CAM match” to see if that address is currently stored in one of the cache lines, basically each line compares itself in parallel and if an entry does match it sends a signal. A matching signal gets decoded to point to the appropriate entry where the data is, otherwise if there's no match it's a “miss” and the address isn't stored in the cache. This is how I think of the moves in the game Apocalypse World: as things happen in the fiction you “CAM match” them against the triggers and if they match then you do the appropriate mechanics, but if they don't match you don't try to engage the move mechanism. Because things like caches are sparesely populated you can't infer too much from the “miss” signal (except that you don't use that cache to service the request), which is analogous to how the “doesn't match any of the moves” signal in AW doesn't say that the action wasn't important or meaningful, just that it didn't trigger the particular mechanics associated with any particular move.

Testing

Specifically, my job was in Pre-silicon Validation. It was our job to try to find bugs in the microprocessor design before it was fabricated into an actual processor. We had software simulators that could simulate how the processor would run, but the simulators were much slower than what the part would be capable of in actual production – for example at one point our simulator ran at about 5 Hz for a processor that was slated to run at 1.5 GHz. This meant we had to be smart about figuring out how to test things well, we couldn't just sloppily throw things at it and hope: we didn't have time to waste on useless tests, and we had to make sure we had found as many bugs as we could because the cycle-time on updating the design files and fabricating a new one could be weeks or months. (One interesting bit of fractal weirdness that occurred during this project was that the processor we were designing was much faster at running our processor-simulator than previous processors had been, so our testing for later versions got much faster because we could use our faster processor to run the simulator software).

In the game design world the kind of testing we care about is playtesting. I still have a pretty strong negative reaction when I see what looks to me like “bad testing”. For example, when I see people using a “beta test” of a game as a VIP access marketing device it gets under my skin because in my world tests should be about tests not about advertising. A few years ago one rather popular indie developer was revising their flagship game and they specifically requested that people running playtests not send them recordings of the sessions because they didn't have time to listen to them – that offended my sensibilities because throwing away visibility into your device-under-test seems crazy to me. There's also a sense that “game designers make bad playtesters” because they have trouble taking off their designer hat and telling you how they would change things in the game rather than just playing. This is true in the sense that often the first “naive approach” to testing something doesn't end up being the best way to test things – it takes some understanding to figure out how to test things well – but I think that game designers are also the only ones who have any incentive to figure out how to develop the skills and techniques to get good at playtesting. I think I have some insight into the playtesting process, but because it's so hard to convince people to actually participate in testing I haven't had a lot of opportunities to be able to translate my abstract ideas into concrete techniques or processes that I could recommend to others.

It's a part

One interesting facet of Intel culture was that we would call what we were making a “part”, the same way you'd use that word to describe the merchandise at an auto parts store. In one sense we were designing this fantastically complex thing that hundreds of people were spending years of their lives on, but in another sense it was just a part that needed to get out the door so that our customers could use it to build the stuff they needed to build. While our thing was special to us, we had this element of vocabulary keeping us grounded: in some ways our thing fit into the same category as any other chip, or even a component like a capacitor. I think there's something virtuous about being able to look at your creations from multiple perspectives, one of which is that a customer in the marketplace has certain expectations about what it is and how it works. I think game design, like any art, has the ability to be personal and expressive, but at the end of the day the thing you create also needs to be a game. There may be no explicit or enforceable specification for what makes something “a game”, just like there's no specification for what makes something “a part”, but I still think it's a useful abstraction to remember that what we're trying to create isn't just our own self-expression but also a thing that other people are going to be using in a way that's somewhat interchangeable with other things in the same category.

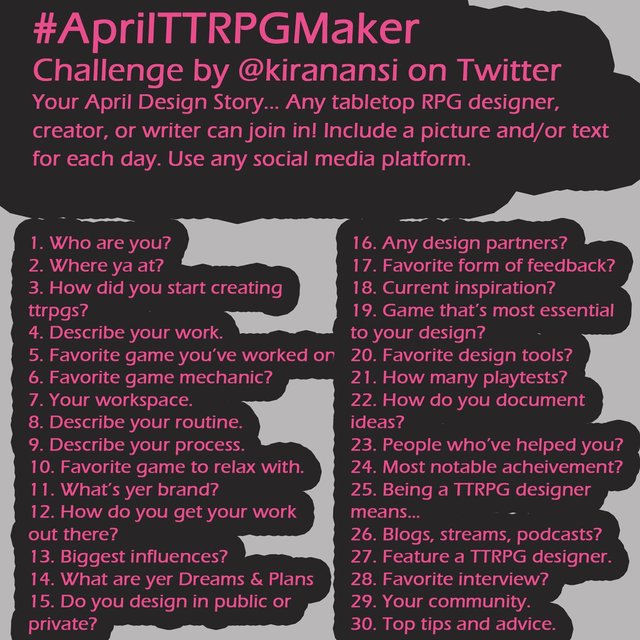

The #AprilTTRPGMaker questions

(From Kira Magrann's twitter)