Life Of A Sailor From 1806

The life of a sailor has never been easy, and during wartime, it is doubly true. It was particularly so in the Royal Navy at the beginning of the 19th century.

Britain was embroiled in a struggle against France, which had recently succumbed to revolution. Napoleon Bonaparte had become ruler and he had a grand vision of spreading French influence across Europe and the British channel. To do that, he needed control of the seas.

Britain’s Royal Navy was all that stood between Napoleon and his almost complete control of Europe. It was not until the Battle of Trafalgar, in 1805, when his fleet was sufficiently weakened, that the British could rest easy knowing a French invasion was impossible.

Across the globe, however, the Royal Navy still fought Napoleon’s ships, which harassed shipping and blockaded ports. Life aboard those ships was always tough, but rarely ever slow.

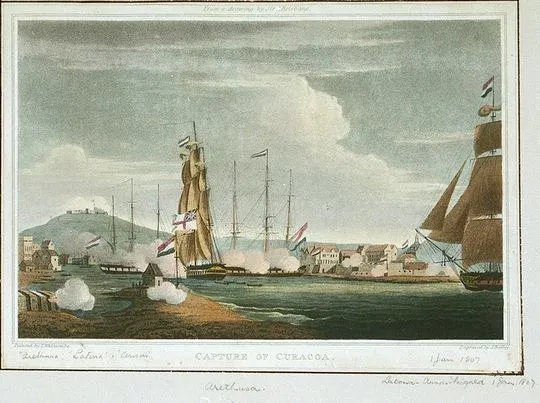

The capture of Curacoa by the Arethusa and the Royal Navy’s fleet;

A sailor, specifically a maintopman, was on the starboard watch aboard HMS Arethusa, in December 1806. The ship was armed with 28, 18 Pounder cannons, and 16, 9 Pounders, with a crew of 280 men. She was sailing towards Curaçao, in the Caribbean, to capture it from the Dutch.

A sketch of a seaman from the late 18th/early 19th century by Thomas Rowlandson;

Morning Watch

At 0340 his day began. With his rigging knife and splicing fid, the mid topman joined his watchmates on deck ready for muster or inspection. Then he climbed 100 feet above deck to his position on the main topgallant yard. From there he could see the horizon for miles around. He was keeping a sharp eye out for shapes along the horizon; another ship could mean anything from news of home to a heated battle.

The main top of the tall ship Balclutha. A yard is the horizontal spars, which held the sails, and moved to catch the wind. The men who served up in these high reaches had to brave rolling seas and high wind;

Mustered again at 0545 the watchmates had to scrub and swab the deck, cleaning it before the day’s work.

Breakfast

At 6 bells on the morning watch, or 0700, the sailor worked his way down to the mess deck. Nine other crewmen joined him for oatmeal and coffee at breakfast.

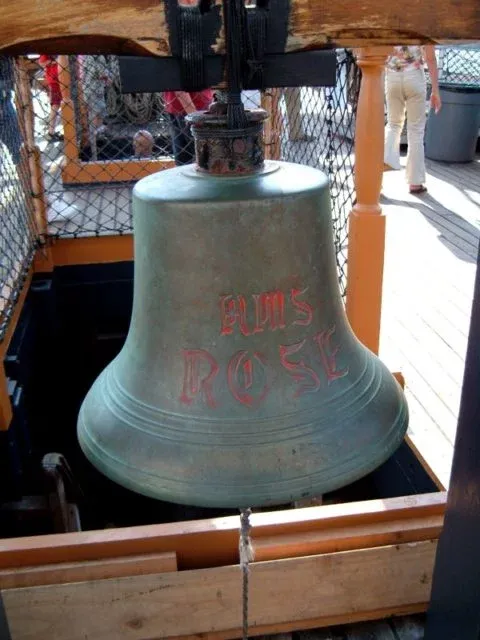

The bell of HMS Rose. It was the main timekeeping device on board. It rang every half hour, and sailors counted the number of strikes to know the time of each watch;

Dinner

At 7 bells in the forenoon watch, 1130, it was dinner time. Usually, a bowl of beef lobscouse, a thick stew of salt beef, potatoes, carrots, and onions and a ship’s biscuit. All washed down with grog made with three parts water to one part rum, with lime juice and a little sugar mixed in.

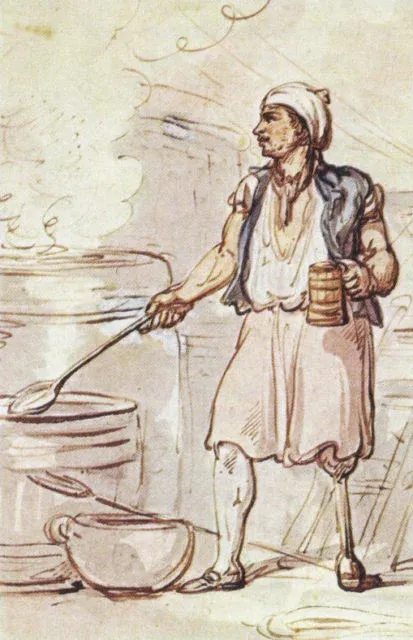

A sketch of a ship’s cook by Thomas Rowlandson;

Afternoon Watch

The entire ship’s crew was called to muster at 1315, and then the sailors returned to their daily duties. The mid topman again climbed aloft into the rigging and kept a keen eye out for other ships. If the ship’s course was to be changed, it was the watchmates’ job to move the sails expertly. Each weighed hundreds of pounds and had to be moved quickly with the help of crewmen hauling on deck.

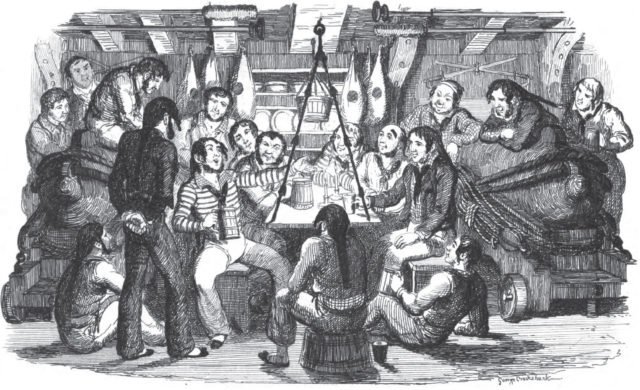

Relaxation, Supper, and another Watch

At 8 bells in the afternoon watch, 1600, it was time for the mid topmen to stand to and relax. Stories, songs, and jokes were shared about, until 1830 when all hands were piped to supper. Afterward, it was back on watch again until 2000 and time for some sleep. At midnight, they were back on deck again, and the process repeated.

A sketch of life below decks. Drink, singing, and camaraderie were the only respites available after a long day of hard work;

It was a tightly regulated schedule, run by the stroke of the bell and the call of a pipe and was the only thing many 18th and early 19th century sailors could be certain of. The weather changed, battles were fought, officers and friends came and went, and ships too, but the bells, the routine, and the work were always constant.

Brave and stalwart men they endured the routine, whether by choice or impressment.