Proust throught the eyes of Jose Ortega y Gasset

In his essay, "The Intellectual and the Other" Jose Ortega y Gasset sets a boundary between the MAN OF SPIRIT and the MAN OF LIFE by formulating their different attitudes towards the world. According to Ortega, the non-intellectual is moving among things that keep his likeness. And he does not even want to question them. It is precisely this kind of activity - the questioning of things - is unknown to the man of life. For him, they are given, and the world as a whole is as it is before his eyes. He faces mysterious, mysterious and unknown things, but these properties do not cause him any particular reaction. They look like the ordinary qualities of things, no less natural and real than color or shape. They do not really care. He does not make a difference between what he thinks he knows what he is and what appears to him as a mystery. For him there is no knowledge or ignorance. His connection to things means simply to have them. His life excludes any influence on what surrounds him in order to make it doubtful, to decompose, to deprive of power, to become a ghost and a vision. On the contrary, in the course of all his life, the non-intellectual keeps on what is here, moving within the boundless, trustworthy, sustainable and established once-and-for-all world. And the intellectual goes just the opposite: he puts things in doubt. And this - according to Jose Ortega y Gasset - is the highest manifestation of affection.

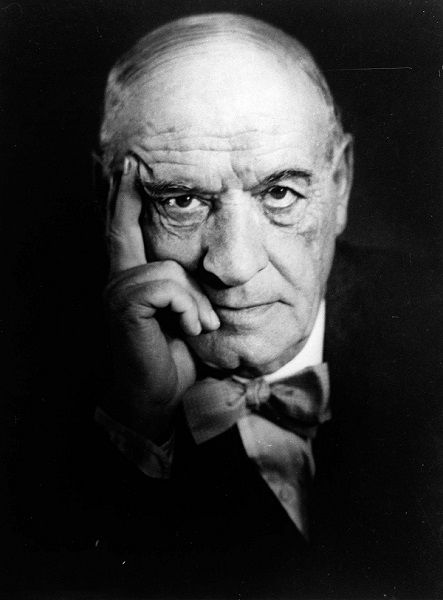

The Spanish philosopher, who lived from 1883 to 1955, views the work of one of the top masters of modern European literature through the prism of his famous formula: "I am the things that surround me." The essay "Time, space and form in the art of Proust" Ortega wrote in 1923 when he was forty years old professor of metaphysics at Madrid University and has already founded the literary series "The Library of Ideas of the XX Century". According to Ortega, Marcel Proust is one of those writers who have had the happiness or genius to encounter a new and rich stream of "stuff". The findings of the French novelist are of a high class because they refer to the most elementary situations relating to the literary object. Namely: the way we look at TIME and get in the SPACE.The themes at Pristus are simple, lead to a non-permanent existence on the surface of the work and represent only minor, additional interest. They are like buoys that are carried without direction in the bottomless stream of memories. To Marcel Proust, writers usually use the memory as a material to restore the past. Since the data stored in the memory is insufficient and from the past reality retains only one random extract, the traditional novelist supplements this data with observations on the present, with any kind of conditional hypotheses and thoughts, thus adding to the authentic material of the mentioned other data, who are false. But Proust's intention, Ortega goes on, is diametrically opposed. He does not want - by using his memories as a material - to restore the old realities; on the contrary, by resorting to all possible means - exploring the present, self-observation, psychological theorizing - wants to achieve a literary restoration of his memories. And so: not the things that are remembered, and the recollection of things is Proust's main theme, concludes Jose Ortega-gasset. For the first time in Prist, the memory ceases to be a material that describes something else but becomes the very thing that is being described. For this reason, the author does not usually add to those parts of the reality that he lacks, but leaves it intact, as he thinks, objectively, incomplete, perhaps even mutilated.

That's why Protest's novel themes are just a pretext and a sort of loophole, through which he can escape into freedom, winged and shivering, the swarm of remembrance. Proudly, Proust has given his work the general title " In search of lost time". He is most careful not to impose on the past the anatomy of the present, and adheres strictly to the principle of non-interference. Proust subdues every desire to recover, and confines himself to describing only what flows from his memory. Instead of rebuilding the lost time, he is pleased to arrange his ruins, Ortega emphasizes. Even simpler and more surprising is Proust's discovery of space. By virtue of living requirements, everything imposes a certain distance from which we must observe it to see it in the most advantageous way. Whoever wishes to see a stone well is approaching him so that he can see his piercing surface. But whoever wishes to see a cathedral well, he will have to give up his desire to see the storms on her stones and move away to significantly expand his field of vision. The magnitude of these distances is determined by the organic utilitarianism that lives in life, notes Ortega. But Proust, who may have been tired of looking at a hand painted always as though it were a monument, is approaching her eyes and covering her horizons, sees surprised how an impressive landscape stands out where the wavy poles of the pores are crowned from the tiny forest of moss. This, of course, is only one comparison: Proust does not care about hands, nor about all the corrupted things, as much as the inner flora and fauna. It corrects our distance in terms of human feelings and breaks with the tradition of describing them monumentally.

This style dominated by the end of the century in the sensitivity of Europeans to art. The impressionist psychologist denies what is usually called the character - the plastic profile of the personality, and sees in it a continuous change, a series of vague states, an always different intertwining of feelings, thoughts, colors, hopes.This reasoning serves us to chronologically fit Proust's intimate tendencies. Swann's love monogram is a case of psychological pooptilism. For the medieval author of Tristan and Isolda, love is an outlined, unambiguous feeling: for him, the original artist of the psychological novel, love is love and nothing more than love. In return, Proust describes a love of Swann, which has no form of love at all. It has everything in it: moments of hot sensuality, lawn colors of distrust, gray habit of habit, gray spots of life fatigue. The only thing that can not be found in it is love. Love occurs, as is the case with a carpet in which, by crossing several threads, a figure is produced, although none of them has the shape of the figure. Without Proust, no literature would be born, which should be read with closed eyes, as Mane's paintings look. For this reason, one has to approach cautiously, approaching Stendal. In many ways the two writers represent two poles and are antagonists. Stendal is primarily a man of imagination: he thinks of intrigues, situations and characters. He does not copy anything: everything is solved by fantasy, a dry, focused fantasy. His souls are so "thoughtful," as might be the line of a Madonna in the paintings of Raphael. Stendal firmly believes in the reality of the characters and strives to paint their unbeatable profile. Proust's personalities, on the contrary, are devoid of a silhouette; they are more variable atmospheric masses, clouds of spirit, which winds and lights transform every minute. He is undoubtedly born with Stendal, "the explorer of the human heart". But while for Stantel the human heart is a solid body with strictly plastic lines, for Pristus our heart is a vague gaseous education that changes in meteorological inconsistency every minute. Between what Stendal is painting and what Proust painting, there is the same distance that Engur shares with Renoir. Engr has painted beautiful women where we could fall in love; Renoir, no - his approach excludes that. The shimmering mass of light points, as a woman at Rönnör represents, gives us the highest sense of juicy flesh; but in order for a woman to be beautiful she must oppose the expansion of the flesh to the strict boundary of a profile. Similarly, Proust's literary and psychological method prevents him from portraying attractive female figures.

In short, Proust brings into literature what could be called a general atmospheric intention. Landscapes, faces, inner and outer world, everything evaporates into a misty, unrealistic thrill. I would say that Proust's universe is made to be perceived as a breath, because everything in it is the environment. In these books nobody is doing anything and nothing is ever happening: everything is a passive series of static situations. And I could not be any other way, because in order to do something, you must first represent something definite. In animals, action always develops as a line drawn from their will, and when this line encounters obstacles, it always re-emerges, and this indicates that a being is opposed to the emerging resistance. This broken line, which is the action of the living being, whether man or animal, is loaded with hidden dynamism, which gives the development a dramatic thrill. But the existence of the Prust Heroes is of a vegetative nature. They, like plants, tolerate their relics naturally and their botanical obedience as if their life is depleted by the chlorophyll function, that same and almost anonymous chemical dialogue, in which the plant is obedient to the principles of the environment. Thus Ortega y Gasset attributes Proust to the intellectual authors whose art acts upon our desire to act and forces us to place things around us in doubt, that is, not just to have them, but to accept them as controversial, unreliable, unsustainable and mysterious, and that is, to love them.

Wow. Amazing post. I read Proust almost 20 years ago now. I know exactly what you mean, especially when you say;

"In short, Proust brings into literature what could be called a general atmospheric intention. Landscapes, faces, inner and outer world, everything evaporates into a misty, unrealistic thrill. I would say that Proust's universe is made to be perceived as a breath, because everything in it is the environment. In these books nobody is doing anything and nothing is ever happening: everything is a passive series of static situations."

Brilliantly stated!

I felt Proust was mapping out his internal thought process in minute detail, and giving a blow by blow account of the ranges and fluctuations of his emotional geography.

His ability to catalogue his internal descent into a complexed state of mind, was a fascinating study of the process.

Incredible post. Thank you for sharing.

Proust, Kafka, Dostoevsky, Stendhal? Who would have thought that one day these names would feature on Steemit? How utterly exciting to find posts of this caliber! Your insightful, well-written literary analyses elevate the discourse at a time in our cultural history when the common denominator seems to be sinking lower and lower. Thank you.

It is sad that you are very right. I'm not sure who said it, maybe Michel Houellebecq or Paul Valerie, that Proust is the last real European. Thank you for the comment and I wish you a wonderful day.

Great post your philosophy