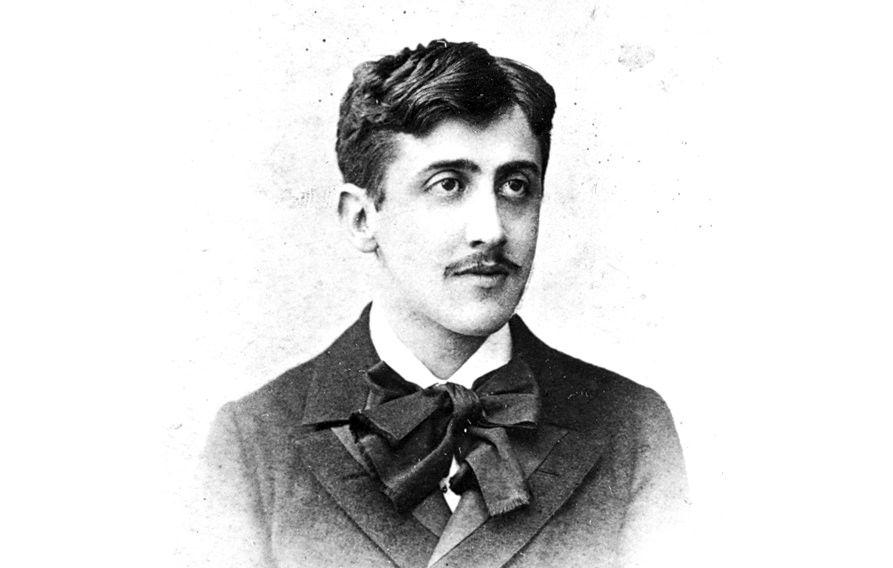

Live and creativity of Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust was born in Otoeu on July 10, 1881 in a rich Jewish family. As a teenager, he enters the vain worldly comedy that takes place every night at the reception of the most visited Parisian lounges through La Belle Epoque. He is an extremely visionary witness and analyst of the decline of the progenitor aristocracy and the rise to unscrupulous wealthy citizens. As a teenager, he collaborates with several literary magazines, but refuses to write about the "Nouvelle Revue Française", whose editor-in-chief is Andre Gidd. In 1913, he published his novel "Swann's Way," at the Grass Publishing House, and in 1919 he received the Gonkur Award for his novel "In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower".

Creativity: The series "Lost Time / In Search of Lost Time /" looks like, according to a French critic, a Gothic cathedral with its rich, complex and large-scale construction. It is a voluminous novel, consisting of seven parts, which traces events that have completed 14 years of Marcel's hero, recovered in his mind through "involuntary memory." In the narrative, Proust splits autobiographical fragments of fictional events, reshapes the perceived concept of time, transforms it from an objectively perceived astronomical term into a subjective sequence of exaggerated unique moments in the consciousness of the writer's novel.

The Paris-based Grace publisher, known in the 1920s, takes over all the costs of publishing the first part of the "Swann's Way" series. By completely neglecting the traditional model of the narrative, Proust becomes a sophisticated observer and analyst of secular life in the aristocratic parlors of Paris. The originality of the narrative manner is the regeneration of the past "from the sphere", through the eyes of an omnipotent narrator. In the first novel, the character Marcel, through a sequential retrospection, recreates his childhood as the reader and commentators of this work have permanently built the episode of the Madeleine. The flavor that comes from the immersion of the sweet in the hot tea unlocks the narrator a long series of associations that lead him to his happy childhood and adolescence. Alberta appeared as a character in the second part of the series "In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower " - a novel that won the Gonkur Prize in 1919. In the novel "The Guermantes Way", Marcel returns to another influential presence in his childhood memories - the old aristocratic family of Guermantes, a pillar of secular society, among which he spends his childhood and youth and describes with a boldly ironic irony.

In "Sodom and Gomorrah" (1921-1922) Marcel analyzes the manners of the secular community of sophisticated young homosexuals, which is formed around an authoritative salon aesthete - Baron Charlyus. The author follows the dramatic development of Marcel's love for the hard-to-reach parlor artist Albertin in the novel The Captivity of Albertin. In "Time Regained," Proust returns to the themes he has explored in his previous novels in the series - Snobbery, Love, Jealousy, Art, Memory and Time. The novelist clarifies in this latest work of "The Lost Time / In Search of Lost Time" the meaning of his ambitious project - to recreate the long past time through the prism of an incurable intellectual insight and deep emotional memory trembling. Marcel Proust's novel might be perceived as the first modern, novel "education cycle" of a young aristocrat who realizes the contribution of childhood and adolescence to building him as a person. Thanks to the magic of memory, the narrator rediscovers his commitment to a world that rises above the collapse of beings and their disappearance in the rhythm of astronomical times. He turns away from his surrounding reality and directs it to the reality he has built up in his mind. Ultimately, in the creation of the series, Proust discovers the vocabulary of a novelist. After desacralising his childhood for the author, one last remedy is to heal himself from his subsequent disappointments and the loss of youth illusions: to give birth to a work by which he comes to the meaning of being by going against the flow of outer, astronomical times. Proust overlays many of the perspectives made within himself during the various stages of his life so far, in his narrative, which ends precisely when the novelist is about to re-edit it for the last time. In the first part "Swann's Way". The storyteller, instigated by a casual association, recalls the world of childhood in Combre, with his dear dear ones - the mother, the grandmother, the old aunt Leoni and Francoise. His daily walks take him in two opposite directions: the road where Swann lives with his daughter Gilbert and the musician Ventoy, still unrecognized genius, and the road to Guermantes, senior descendant aristocrats who seem distant, almost unreal to the narrator. In the second part there is a single narrative ("One Love of Swann"), which recreates the passionate enthusiasm of Swann for the famous demi-mentor Odette de Cresci, who later became his wife. Admitted to the highest aristocratic society, Swann regularly visits the Verduren family, a rich bourgeoisie with intellectual pretensions.

In the third part, the narrator presents the mischief through which his teenage love passes to Gilbert in the atmosphere that reigns to Champs-Élysées. There are two related stories on the way to Swann: the first is played around Marcel, an earlier version of the Narrator, traces the experiences and memories of the French town of Combre. It is inspired by the "bursts of memory" that fill it when it sinks the sweet cookie into a hot tea. The narrator discusses his fear of bedtime in bed. He is the creature of the habit and does not like to wake up in the middle of the night and not know where he is. He claims that people are predestined by the things that surround them, and they have to stitch their identities one by one every time they wake up. Young Marcel is very nervous that he has to fall asleep that he is eagerly awaiting the kiss of his mother every night. He says that if he does not get his night, he'll be painfully sleepless. One night, when Charles Swann, a friend of his grandmother and grandfather, is a guest of his mother, she fails to wish him a "good night" with a kiss. He can not fall asleep until Swann's departure and looks so saddened and regretful that even his tough, otherwise dad, exhorts Mama to sleep in Marcel's room. The narrator follows the stages of his propensity for writing back in time, even to Comber. His grandmother, his grandfather and his friends urged him to read and introduced him to Bergot, who became his beloved author. Marcel has an intoxicating awe of the powerful beauty of the landscape surrounding Comber, especially in front of the blooming past the path leading to the house of Swann flowers. He likes to fall asleep in the shade of their colors and wander around Comber, where he admired the city church in particular. He likes to contemplate the reflection of the sun on the tiles of the bell tower of the church. So Marcel decides to become a writer and describes what he sees with all his zeal.

Proust, one of the Great of French literature, if not the greatest.

I remember my school days, tackling his work like a climber tackles Mount Everest. It was arduous work, and I never got to plant my victory flag at the end of the last volume despite a valiant effort on my part.

I enjoyed reading your post which inspired me to relive the magic moment when the memory hits, and I would like to share one paragraph which, like the petite madeleine, is best savored in French (followed by the English version). Proust is known for his ultra long yet elegant sentences. I find they mirror the sophistication of his thinking and his artistic sensitivity. As to the way he weaves a rich vocabulary into these formidable sentences, it gives us a prose of the utmost poetic beauty. Enjoy!

“Et tout d’un coup le souvenir m’est apparu. Ce goût, c’était celui du petit morceau de madeleine que le dimanche matin à Combray (parce que ce jour-là je ne sortais pas avant l’heure de la messe), quand j’allais lui dire bonjour dans sa chambre, ma tante Léonie m’offrait après l’avoir trempé dans son infusion de thé ou de tilleul. La vue de la petite madeleine ne m’avait rien rappelé avant que je n’y eusse goûté ; peut-être parce que, en ayant souvent aperçu depuis, sans en manger, sur les tablettes des pâtissiers, leur image avait quitté ces jours de Combray pour se lier à d’autres plus récents ; peut-être parce que, de ces souvenirs abandonnés si longtemps hors de la mémoire, rien ne survivait, tout s’était désagrégé ; les formes — et celle aussi du petit coquillage de pâtisserie, si grassement sensuel sous son plissage sévère et dévot — s’étaient abolies, ou, ensommeillées, avaient perdu la force d’expansion qui leur eût permis de rejoindre la conscience. Mais, quand d’un passé ancien rien ne subsiste, après la mort des êtres, après la destruction des choses, seules, plus frêles mais plus vivaces, plus immatérielles, plus persistantes, plus fidèles, l’odeur et la saveur restent encore longtemps, comme des âmes, à se rappeler, à attendre, à espérer, sur la ruine de tout le reste, à porter sans fléchir, sur leur gouttelette presque impalpable, l’édifice immense du souvenir.”

« And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom , my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it; perhaps because I had so often seen such things in the meantime, without tasting them, on the trays in pastry-cooks' windows, that their image had dissociated itself from those Combray days to take its place among others more recent; perhaps because of those memories, so long abandoned and put out of mind, nothing now survived, everything was scattered; the shapes of things, including that of the little scallop-shell of pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious folds, were either obliterated or had been so long dormant as to have lost the power of expansion which would have allowed them to resume their place in my consciousness. But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.«

When it comes to Marcel Proust and several other writers and poets, I really regret that I am not knowing the French language. I hope to fix this soon. Thank you for the quote. :)

The English version is pretty good, so I hope you still enjoyed reading the quote, but it is a reality that something is always lost in translation, no matter how good it is, and it is particularly so for the geniuses of literature and poetry because the use of language is a literary dimension in itself. Each word, each alliteration, each expression, the cadence of each syllable is carefully weighted the way that a painter will choose a Prussian Blue over a Midnight Blue or a Royal Blue.

Inevitably we are limited in the number of languages we speak, and I hope that you too have some great works in your native tongue. Judging from the nature and variety of your posts, you are quite an international cultural traveler, and that’s pretty cool 🙂

Nice read. I leave an upvote for this article thumbsup

Thank you :)

Wonderful post...I really need to get around to reading Proust!

You are welcome :)