The Late Iron Age of Southern Africa: Final Part

Dear Reader

In this following series of posts we are covering the Late Iron Age of Southern Africa, I highly encourage you to please read the Introduction, Shona Origins - Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe posts to this series to bring you update to date with the information and terminology we have covered so far.

The Late Iron Age of Southern Africa: Final Part

The Late Iron Age in the Soutpansberg and the origins of the Venda

In an ethnohistorical study of the Venda of the Limpopo Province, Jannie Loubser (1989 & 1991) investigated a large number of archaeological sites north and south of the Soutpansberg mountain range. His study of , in particular, pottery styles and settlement data, as well as the correlation of these with the oral traditions of the Venda and linguistic data, enabled him to compile the following chronology for the origins of the Venda.

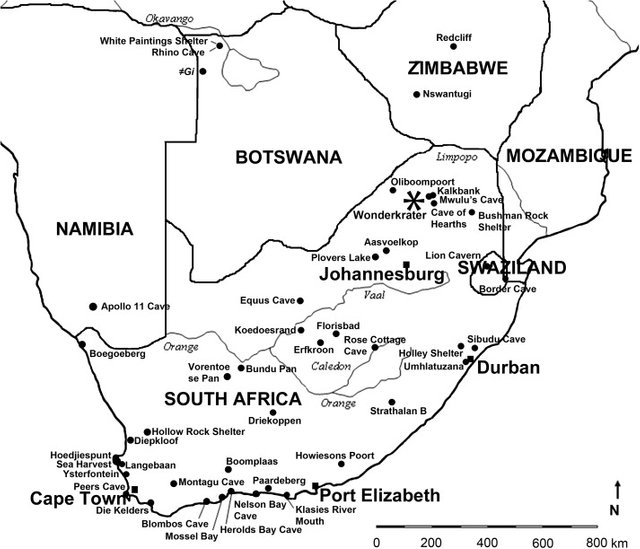

Between AD 1300 and AD 1450 sites with typical Mapungubwe ceramics occurred north of the Soutpansberg. This pottery was probably made by early Shona speakers, since the evidence from Great Zimbabwe and Khami in Zimbabwe indicates that the Mapungubwe style eventually developed into that of the historically known Shona. Princess Hill, Vhuneyla, Mutamba and Tshitaka-tsha-Makoleni are amongst those sites north of the Soutpansberg which yielded Mapungubwe style pottery. During the same period a new pottery style, the so-called Moloko Tradition, (which I cover next), appeared south of the Soutpansberg and replaced the earlier Eiland style with herringbone and cross-hatched decorative patterns. As indicated earlier, the Eiland pottery style represents the last phase of a facies (variant) of the Kalundu Tradition in large part of the area north of Vaal River. The Moloko Tradition is associated with the Sotho-Tswana; and at this stage mainly Shona speakers lived north of the mountain range and Sotho speakers south of the mountain.

In about AD 1450 a new pottery style appeared north of the Soutpansberg which can be associated with the arrival of new Shona migrants from Zimbabwe. This pottery style, which is typified as band and panel decorations with chevrons, diamonds and squares combined with ochre and graphite, is known as Khami ceramics. The Khami Tradition had evolved out of the Great Zimbabwe Tradition, and the new Shona rulers built similar stone "palaces" (misanda in Venda) north of the Soutpansberg at, for example, Machemma, Verulam and Tshitaka-tsha-Makoleni. Although the ruling elite of this Shona migrant group only settled north of the Soutpansberg, a large measure of contact took place with Moloko people to the south of the mountain range. This is indicated by the presence of Khami ceramics on Moloko sites such as Tavhatshena and Manavhela.

As a result of this contact, a new pottery style emerged at about AD 1500, which is defined by Loubser as the Tavhatshena style. According to Loubser the amalgamation of the Khami and the Moloko pottery styles into the Tavhatshena style reflects the development of a new language from the merger of Shona and Sotho. It is also significant that, by AD 1600, the Tavhatshena style had evolved into the Letaba style, which occurred both north and south of the Soutpansberg. The Letaba style, characterised by an incised band cross-hatching or counter hatched triangles on the shoulder, with graphite burnish (polish/sheen) is today still associated with the Venda.

Loubser (1989:57-58) comments as follows:

Now if it is accepted that the overlap between Khami and Moloko indicates the close interaction between Shona and Sotho speakers, then the development of Tavhatshena and Letaba ceramics from this interaction must indicate the origin of the Venda language is basically an amalgamation of Shona and Sotho.

The Letaba style and the Venda language were also adopted by the Singo, the current ruling group among the Venda, after their migration from Zimbabwe to the Soutpansberg between AD 1680 and AD 1700. The Singo settled among the Venda and established their capital, Dzata, in the Nzhelele valley.

The Moloko Tradition and Sotho-Tswana origins

As indicated earlier, there is a difference of opinion between, especially, TM Evers and RJ Mason on the question of cultural continuity during the Iron Age. According to Mason, the origins of the Late Iron Age communities of the area north of the Vaal River must be sought in the Early Iron Age: in other words, the cultural units of the Late Iron Age evolved from the Early Iron Age complex as, for example, represented at Broederstroom. Mason continues to hold this view, despite the fact that he did not discover any Iron AGe sites in the former southern and western Transvaal (Gauteng and North West) dated to between AD 600 and AD 1100 (in other words, there is a gap in his cultural sequence). Mason calls this cultural tradition the Oori Tradition and, according to him, it represents the origins and development of the Sotho-Tswana. "Oori" is a corruption by early travelers and hunters in the former Transvaal of Odi, the Tswana name for Crocodile River.

Evers and other researchers discern a break in pottery styles in large parts of the area north of the Vaal River in about the 13th century AD. The new style, known as Moloko, replaces the Eiland ceramic style earlier referred to, and reflects the migration of Sotho-Tswana to South Africa. The name Moloko is derived from the old Pedi (North Sotho) word for tribe and, according to Evers, signifies the manner in which the Sotho-Tswana spread over the country through a process of lineage segmentation or splitting of tribes. The Moloko pottery style is defined by Evers as follows:

Its principle decoration components are bands of hatching or multiple incision spaced down the vessel, often with the untextured bands coloured black or red. Triangular and arcade or chevron motifs are also found.

Mason assigns the Early Moloko to a so-called Middle Iron Age. The Moloko Tradition can be divided into two phases: an early phase in which sites were usually located at the foot of hills and contained little or no stonewalling; and a later phase characterised by extensive stone wall complexes which were often erected on hills. The best-preserved Early Moloko site is Olifantspoort 29/72 near Rustenburg. It consists of the remains of 20 huts arranged around an elliptical open space, probably a cattle kraal. The charred remains of two sorghum species were found on the excavated hut floors, one of which yielded a well-preserved wooden mortar sunk into the floor. Radiocarbon dates for some Early Moloko sites are as follows:

- Nagome 3 near Phalaborwa (AD 1165 +- 36 & AD 1270 +- 45)

- Icon near Alldays (AD 1330 +- 50)

- Tavhatshena near Louis Trichardt (AD 1290 +- 80)

- Olifantspoort 29/72 near Rustenburg (AD 1510 +- 90)

- Rietfontein near Zeerust (AD 1590 +- 50)

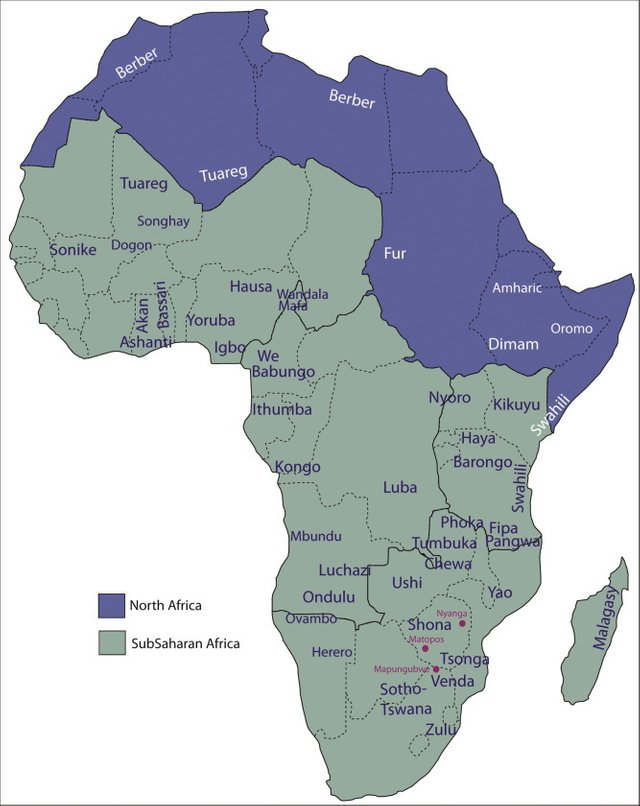

- Rooiberg near Thabazimbi (AD 1580 +- 30)

These dates have led to the inference that the Moloko Tradition and the Sotho-Tswana entered the country from the north-east and spread in a south-westerly direction until they eventually reached the Free State. According to Huffman the origins of the Early Moloko are somewhere in Northern Mozambique or Southern Tanzania. That Sotho-Tswana as well as the Nguni languages evolved somewhere in East Africa is also confirmed the linguistic research of JA Louw and Rosalie Finlayson (1990).

There is still no clarity about why the Late Iron Age inhabitants started building with stone or exactly when the Late Moloko phase commenced. According to Mike Evers (1988:129), the majority of radiocarbon dates indicate that the stone wall phase began in about the middle of the 17th century AD. A few dates which suggest that some of the stone-walled complexes had been occupied earlier derive from the base of ash heaps and, according to him, may not date the human occupation of the sites.

During the second half of the 18th century, some of these stone walled complexes, especially those occupied by Tswana communities in what is now known as the North West Province, expanded into enormously large settlements covering several kilometres. Good examples of these "mega sites" as they have been described by Revil Mason, are Molokwane, the capital of the Bakwena-ba-Modimosana-ba-Mmatau near present-day Rustenburg, and Kaditshwene, the capital of the Hurutshe near the modern town of Zeerust. According to Julius Pistorius (1992:3) the stone ruins of Molokwane extend over at least four to five square kilometres. On his visit to Kaditshwene in August 1821 the Wesleyan-Methodist missionary, Stephen Kay, described the Hurutshe capital as most probably the largest town he had encountered in the South African interior on his journey from Cape Town, John Campbell, a director of the London Missionary Society who had visited Kaditshwene from 4 to 12 May 1820, estimated its population at 16 000 to 20 000. The large populations of these two capitals were grouped into three settlements zones, namely a central division, an upper or right-hand division, and a lower or left-hand division. The core of the central division, known as the kgosing(the chief or king's place), contained the chief or king''s ward, which was located next to or around the main cattle enclosure and central court (kgotla). Each ward contained a number of family units, whose members often shared a common line of descent and who were placed under the leadership of a headman or lesser chief.

Factors which contributed to this process of aggregation include population growth, reduced access to unoccupied land, political centralisation, and the incorporation of foreign groups through the ward system. It has also been suggested that these large settlements among the Tswana were the outcome of military pressure as a result of raids by the Kora (Korana) and the Griqua from the south, as well as escalating conflicts among neighbouring Tswana chiefdoms, which preceded the upheavals of the so-called difaqane or mfecane. Both Molokwane and Kaditshwene were evacuated in the early 1830s during the difaqane, a period of conflict during which many African communities were attacked and dislodged, first, by refugee Sotho groups, who had been driven from the Free State and, finally, by the Ndebele (Matabele) of Mzilikazi, who had migrated from KwaZulu-Natal.

The Late Iron Age in Kwa-Zulu Natal and the prehistory of Nguni

An early phase of the Late Iron Age has been uncovered at Blackburn, about 20km of North of Durban and in Moor Park in Kwa-Zulu Natal. Blackburn dates from the 11th century AD and Moor Park from the 13th and 14th century AD. The ceramic style of Blackburn represents a break with that of the Early Iron Age. Since there is a resemblance between Blackburn pottery and Nguni pottery. Huffman postulates that Blackburn reflects the migration of the Nguni to KwaZulu-Natal and later to Transkei. According to Huffman, the origins of the Blackburn tradition must be sought somewhere in East Africa, probably in northern Mozambique or southern Tanzania.

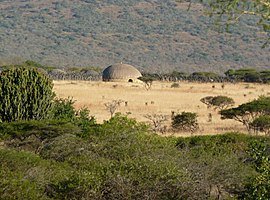

The Late Iron Age communities gradually expanded into the grasslands of the Kwazulu-Natal interior. Sites belonging to the final phase of the Late Iron Age can often be linked with historically known Nguni groups. One such site is Nqabeni on the Babanango plateau between the Thukela and the White Mfolozi Rivers. The site comprises eight stock byres built out of stone. The faunal remains confirm that cattle, sheep and goats were kept. The excavations also yielded charred seeds of sorghum, cowpeas and maize. The site dates from the 18th century AD and can be linked to the Khumalo chiefdom on the basis of oral traditions.

Excavations have also been carried out at several 19th century Zulu capitals, for example at Mgungundlovu. the stronghold of the Zulu king, Dingane. Although there are contemporary descriptions of Mgungundlovu, which was inhabited from 1829 to 1838, a preliminary archaeological investigation has already added valuable new information on the size and layout of the town. Excavators have discovered that the approximately 800 warrior huts were closely packed together and that, between them, these huts could have housed about 5000 warriors. More recently, the main hut of king Dingane himself was located and excavated.

The way of life of the Late Iron Age agriculturists

The Late Iron Age is characterised by a greater degree of economic specialisation. Each village was no longer a self-sufficient unit; instead; there was a greater regional interdependency and more emphasis on trade as can be seen from the large number of imported glass beads found on some sites.

The greater specialisation can be attributed largely to the unequal distribution of natural resources, especially mineral resources, over the landscape. Iron slag no longer occurs on virtually every site; instead; there are a number of main centres which specialised in the mining and production of iron. Phalaborwa in the Limpopo Province was one of the most important iron and copper production centres. Iron was used mainly to manufacture hoes, knife-blades, axes, spears, adzes, awls and metalworking tools. It would also appear that little iron was smelted by the southern Nguni, the Xhosa. On highveld sites a large number of bones tools are found which probably indicate that bone tools, rather than iron tools, were used to prepare skins.

Copper production was even more restricted and there is little evidence of copper-working south of Vaal and Nkotmati Rivers. Copper and bronze were used to manufacture ornaments such as beads, earrings and arm bangles. Tin was mined at Rooiberg near Warmbaths/Bela-Bela in the Limpopo Province, while gold objects, particularly beads, were recovered from a few sites such as Mapungubwe and Machemma in the Limpopo Province and Thulamela in the Kruger National Park. Metal products were important trade items during the Late Iron Age.

The settlement pattern of the Late Iron Age also reflects certain changes. It was during the Late Iron Age that the grasslands of the highveld of Gauteng, the Free State and Interior of KwaZulu-Natal and the Transkei were first settled. Another feature distinguishing the Late Iron Age is the large-scale use which was made of stone for building purposes, a fact which makes the discovery of sites easier (partially because such sites can be spotted with the aid of aerial photographs). The sheer number of sites documented alone demonstrates a population increase during the Late Iron Age. At the end of the 18th century there also emerged exceptionally large settlements such as Molokowane and Kaditshwene, a development reflecting increasing political amalgamation and centralisation.

Although agriculture still played a vital role, cattle farming, in particular, became increasingly important. Archaeologically, this is attested to by the prominent position of cattle byres on sites, the occurrence of thick dung deposits in some byres, and the fact that, on most sites, faunal collections are dominated by cattle bones. Ethnographic accounts of the historically known African societies of South Africa, with which the Late Iron Age can be linked, confirm that cattle were symbols of power and prosperity, and that they were used as trade items and for the payment of tribute and marriage goods.

And that, Dear Readers brings us to the end of the Prehistory of Southern Africa.

Thank you for reading

Images are linked to their sources in their description and references are stated below.

Authors and Text Titles

Eloff & Meyer: 1981 - The Greefswald sites: Guide to archaeological sites in the Northern and Eastern Transvaal

Meyer: 1998 - The archaeological sites of Greefswald

Inskeep: 1978 - The peopling of southern Africa

Vogel: 1998 - Radiocarbon dating of Iron Age sites on Greefswald

Huffman: 1982 - Archaeology and ethnography of the African Iron Age

Sharma Saitowitz: 1998 - The archaeological Sites of Greefswald

Voigt E A: 1983 - Mapungubwe

Oddy A: 1984 - Gold in the southern Africa Iron Age

Martin Hall: Prehistoric Pastoralism in southern Africa

Peter Garlake:Pastoralism and Great Zimbabwe

Phillipson: African Archaeology

Thank you @foundation for this amazing SteemSTEM gif

This is fantastically written!

I have been blessed with the opportunity to visit some of these sites along with my father (whom you quoted in the article, Dr. Julius Pistorius). Our last trip was to the Rooiberge.

I have awesome memories of digging up a lot of pottery and human remains along with his team and was always included in his trips. I missed school on many occasions and he always told me to just tell my teacher, "I was on an archaeological expedition with my dad". Can't really argue with that!

Keep up the excellent work!

edit

One of the photos I took at Rooiberg.

OMG!!!!!!!!

What an honour to meet you and I am truly truly humbled by your comment:)

You made a dream come true!!!!!!

You sure know how to rub it in to make a guy feel jealous (lol).

I will try my utmost best:)

Thank you so much for the comment and support!!!!

Haha you're welcome! I can pass this along to my dad, as well, if you would like his opinion? I contacted you on Steemit chat, we can discuss it there.

I really want you to become a member of SteemSTEM. I will send you the link to the chatroom via Steemit chat:)

Cool, waiting in anticipation! :)

Link sent:)

This is a fine piece of work. I will print it out in order to bring my daughters up to date with our African history. Thanks so very much.

This the best comment I could ever ask for. I have finally achieved one of my biggest Goals on Steemit!

I always wanted someone to hand down my work to youngsters because that is exactly what I do with other authors on Steemit as well.

I really appreciate it!!!

Thank you so much:)

Been waiting for the concluding part of the late iron age of Southern Africa. Awesome piece buddy.

After Iron age, what comes next?

Thank you :)

The Late Iron Age concludes the Prehistory (unwritten) aspect thereafter we go into History (written) aspect :)

That's great buddy. Is the unwritten aspect also called "oral tradition"?

That is correct:)

Great end to the series, even though i have not had time to go through everything, the few I have read are quite interesting. Well done zest, I probably need to learn some tips from your concerning the structuring of blogs.

Hey buddy!!!

Thank you so much for the comment and support.

Whatever tips you require please free to DM me on the chat:)

Quite a long read but very interesting, I have always wondered how these relatively ancient people were able to mine let's say iron if their hardest material was in fact iron, in reality how were they able to mine the first iron to produce tools? How could they extract it? I know the answer must be easy but I never get to understand this. And since really the interest is just momentary I never take the time to google it.

The knowledge of ore mining and smelting was brought down to southern Africa from the migrating Bantu people.

Thank you for the comment and support @gduran:)

you've been missed buddy!

hope all is great :)

Howzit Boet:)

Thank you so much!!!

I always enjoy reading your historical and ofcourse mystrious stories and articles.

Thank you sir ^^

Thank you @farseer for taking the time to read and comment. Much appreciated:)

excellent post greetings already voted and done reesteem

Thank you!!!!!!!!

A very interesting and inspiring post, always interested in history and undiscovered things, I think a Indiana Jones brought me to this, hehehe, cool profile pic!

Best regards

Tom

I hope he keeps bringing you back!!!

Thanks Tom:)

hahahaha, now he brought me to Thailand, but I don't want back, hehehehe

👍