The History of Music: The Invention of Notation

Last month I wrote about how there were some vague forms of written music many thousands of years ago, but these examples and relics were pretty useless when it came down to standardized details. Most punishingly, there was until comparatively recently no sense of rhythm and certainly no reference point.

To figure out how we solved this, we first need to explore why that even mattered in the first place. To do that, we need to skip ahead a few centuries.

A thousand years after Pythagoras' revelations, the Roman senator Boethius (477–524 AD) took the ideas from Greece to Western Europe which was then picked up by Pope Gregory (590- 604 AD) who was starting up some popular music schools.

At this time, there was already endless frustration about music's tendency to fade away forever, as the only way to store music until this point was with our puny brains, passing songs on through diligent students and word-of-mouth. The greatest song in the Universe could very well have already been written. We just... forgot how it went.

Thankfully, music was pretty basic in Medieval times, with God being the main emphasis rather than musical complexity. In fact, all of the known music at this point was entirely monophonic, or 'one sound'. Everybody in a choir would sing exactly the same thing. This is what we call Plainchant and I'm sure you're familiar with its sound:

This music is much easier to write down since it only requires a single, simple melody, and indeed this is where we start seeing the first form of music notation coming into place.

Neume Notation

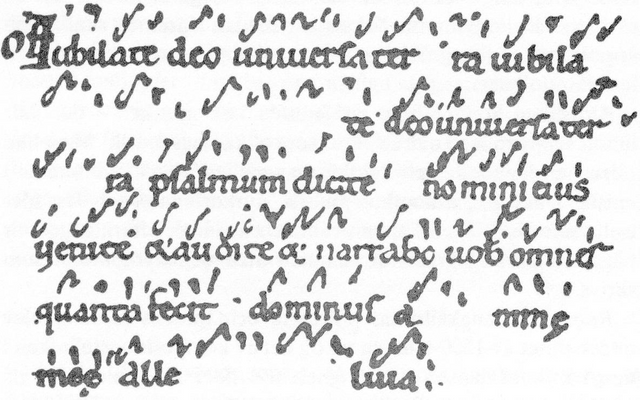

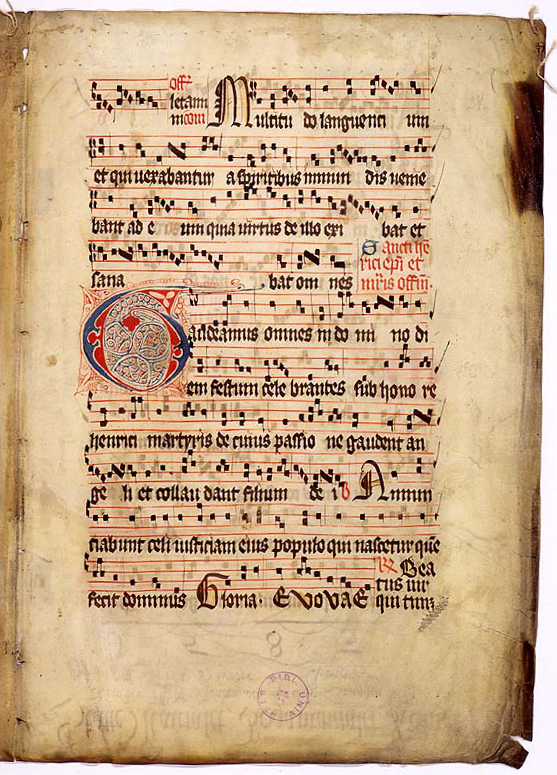

What you hear above is unfortunately only our best interpretation of what the intended song was to sound like because Neume notation, drafted by St Isidore (650AD) and appeared proper around the 9th century, was functionally useless by today's standards. In fact, Neume notation was mostly used as educational guidance; hints for a song that a student has already learned. It couldn't possibly serve as anything more, as neume music was still at this point little more than squiggles above the liturgical text:

Public Domain

Public DomainIf you listened to the music above, you may have recognized it as 'Gregorian Chant'. However, in order to be a Gregorian chant, it has to be a piece of music specifically written down by Pope Gregory I who, according to legend, was approached by the holy spirit in the form of a dove who would sing beautiful melodies for him to have transcribed down by a literate servant.

For the eagle-eyed out there, you may notice a problem with this; Gregory died some centuries before written notation was even invented. So there is, to this day. a problem in the timelines of history. The only way his music could realistically have survived was to be memorized by hardworking students and passed on as accurately as possible until the day they were written down sometime after the 9th century.

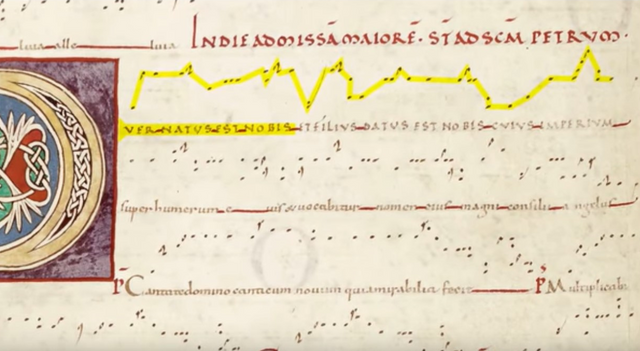

Eventually, there were various improvements to Neume notation, such as around 1050AD, where we find some manuscript of Puer Natus Est demonstrating vertical relationships between notes, giving a clue as to how high and low one should sing - You may even be able to follow along intuitively if you listen and read:

Public Domain

Even here though, we STILL didn't know where to actually start... This may seem trivial at first - as long as everyone in the choir agrees on a starting point on any given session, they can all just sing in reference to that. But music doesn't quite work like that.

This missing detail was a problem in particular because music consists of tones and semitones. If we don't know where to start, how do we know which interval to jump? Take a look at the keyboard below as an example. Bear in mind, music would only be following the natural 'pure' intervals laid out by Pythagoras. No G-sharps or B-flats. This means, Only white notes on the piano would be sung.

As you can see in red, there are two steps you need to make to get from one white key to the next, with a semitone - or black key - in between. This forms a tone. In both the yellow and green parts, there are no black notes in between, thus the distance is only a single semitone. Without knowing this due to the incomplete invention of Neume music, you had no way of knowing which notes are hitting the green and yellow semitone intervals and the red tone intervals.

How annoying.

It wasn't until a certain monk came along, exceptionally frustrated with these literary limitations to such an extent that he eventually took the reigns and patched up these gaping wounds of music.

Guido d'Arezzo

By this point, 1,000AD, we're 1,500 years past the revelations of Pythagoras. For perspective, the Agricultural Revolution which set the stage for the Industrial Revolution and lead to where we are today, all happened in the last 250 years or so. If Guido was here today, the details laid out by Pythagoras occurred when the Persian and the Eastern Roman Empires were at war, and close to nothing developed in between.

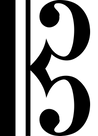

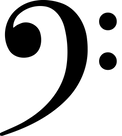

Guido was born roughly 992AD and among many things, he invented the concept of the clef. Looking at the piano above, the green and yellow parts are E-F and B-C respectively. since these were the two important parts of the scale messing everything up, Guido pinned two clefs here - the F and the C clef, which indicated on a series of four horizontal lines where those two semitones were - everything was a tone except the notes BELOW these two clefs. Fantastic! Now we have reference points at least for intervals of the music!

It was now possible to read music! Of course, Guido's clefs looked very little like those above and more like old fashioned telephones:

Guido d'Arezzo accomplished much more than this, including the Guidonian Hand used as a method of learning music substantially faster than before, which also came alongside his creation of Solfege (do-re-mi-fa-so etc). However, this may be left for another post more focussed as a biography to him,

Most importantly, music could now be performed the same at one church compared to another in an entirely different country!

Now we're getting somewhere.

Square Neumes

Neume notation was slowly evolving, and by the 13th century, we start to see a significant change. Neumes - the squiggly lines above text - were no longer squiggly lines, but instead blocks, squares, sometimes connected with one another to indicate directional runs and other things:

Public Domain

Once again, you can actually follow this music above - Introit Gaudeamus Omnes - in the following excerpt, starting from the right of that gigantic circular G. Just bear in mind that when notes are directly above another note, this does not indicate two different notes, but the lower note played before the higher one. Give it a go! Just follow the squares, with the words in your peripheral vision:

Assuming anyone tried, congratulations! You're learning to read music!

Rhythm

So we solved the problem of reference points, but we still have no indication of rhythm. This was typically fine as things were, and really quite free and liberating. However, as polyphony - or 'many sounds' started to evolve, it became harder and harder to keep things in control, with multiple melodies getting mixed up and out of sync constantly.

So how did we come to solve that?

Well, I'll save that for the next episode!

Sources: Guido d'Arezzo | Neume Notation | Guidonian Hand | Gregorian Chant | Pope Gregory I | Clefs | Pythagorean Tuning

Dear @mobbs,

astonishing post you wrote there. I think it's as ridiculous as unlikely but today I learned about this very topic in school. You wrote quite a few things I didn't hear about in class today. Mostly the clef development by Guido d'Arezzo I didn't know about yet, so thanks for that ;-)

Before I dive in let me excuse the formatting, I know it's terribly reader unfriendly, but I have forgot a lot of the tricks apparently.

Regarding the clefs I can give a little additional information: in your post you mentioned the C and the F clef, and included a picture which displays them in their today most commonly used form. What I think is really interesting how these clefs developed to look how they do today. I think the easiest to see it in the G clef, which apparently wasn't invented by Guido d'Arezzo. I'm sure everyone knows how it looks:

Public Domain

I found pics on a blog which display the development:

Source

I think you can see that the first one on the picture vaguely resembles a G, and how it slowly developed into the probably most used clef as of today.

The F clef is a little harder to imagine as an F if you look at it:

Public Domain

If you look at the picture showing the development, it gets very clear:

Source

Parts of the F just vanished and just left the two points behind, and the rest just curled up (just like the G clef) and now it looks like the well known clef. It's crazy, isn't it? =)

To add a little more musical context to all of this the G clef indicates where a G is in on the sheet of music, and to see it you just have to look where the clef "curls up". If a line passes through that, the G is right there. It is very very common for notation of singing parts, violin parts, the upper part of a piano notation etc. It is also known as treble clef.

For the F clef the F is pretty easy to see as it is just between the two points the horizontal lines of the letter F left behind. The F clef is used mostly for bass parts. Be it for an electric bass, a double bass, the left hand of a pianist or the bass in a choir.

The C clef isn't used very often, but it can be used can be used pretty often. As far as I know, if it is used, it is used either as a tenor or alto clef with the center of the clef being either on the line above the middle line or on the middle line respectively. Rarely you see in in choir music, it's not too unusual for orchestral instruments though.

Just a little fun fact to end my comment: the square neume notation is still sometimes seen if you sing in a church choir (I used to sing a few things written in it) so it hasn't entirely died out yet (I highly doubt anybody uses it for new music though)

Thanks again for your marvelous post, it's great to see such interesting topics brought up on Steem.

Hey great addition thanks!

Not only does it vaguely resemble a G, but it exactly resembles the G in the music image in my post above:

I'm certain I will be digging deeper into the clefs at a later point in this series!

I'm glad you appreciate it, it actually took me a while to put the class this is based on into words of much more detail and format

This post has been voted on by the SteemSTEM curation team and voting trail. It is elligible for support from @curie and @minnowbooster.

If you appreciate the work we are doing, then consider supporting our witness @stem.witness. Additional witness support to the curie witness would be appreciated as well.

For additional information please join us on the SteemSTEM discord and to get to know the rest of the community!

Thanks for having used the steemstem.io app. This granted you a stronger support from SteemSTEM. Note that including @steemstem in the list of beneficiaries of this post could have yielded an even more important support.