The Art and Science of Successful Scientific Grant Writing - Part 2

This post is a continuation of my earlier article (The Art and Science of Successful Scientific Grant Writing - Part 1: https://steemit.com/steemstem/@davidrhodes124/the-art-and-science-of-successful-scientific-grant-writing-part-1) and will focus in more detail on preparation of the first draft of the Project Description.

Project Description (first draft)

O.K., you have chosen a working title for your proposal, you have selected a suitable granting agency, and have identified a suitable program area within that agency, downloaded the relevant guidelines, prepared a 1 page Project Summary, and may even have contacted the program director to ask if the subject matter is appropriate for submission, and/or sought clarification on the deadline date for submission (see Part 1).

The next task is to develop your first draft of a Project Description, using your Project Summary as a guide or road-map. As I mentioned in Part 1, ideally you should begin preparing this first draft at least 12 weeks before the deadline for submission. Some people do their best writing at night, others in the morning. I always recommend selecting your most productive time of day and devoting about 1 hour per day to writing your Project Description. If you succeed in writing only one-half page per day, and are consistent with this, you will have generated a 15 page first draft within a month, leaving a good 8 weeks for further revisions and completing other tasks (such as preparing your curriculum vitae, preparing a budget and budget justification, completing certification forms, cover page, facilities and equipment page, current and pending support page, and identifying potential collaborators).

I recommend breaking down your first draft of your Project Description into the following sections initially:

- Introduction/background/literature review

- Preliminary data

- Rationale and significance

- Statement of hypothesis/hypotheses and list of objectives/aims

- Experimental plan or experimental approach, including expected outcomes of each aim or objective

- Potential pitfalls and alternative strategies

- Conclusions - a brief discussion of how the anticipated outcomes will help move the field forward and towards your long-range goals

- Data management plan

- References/literature cited

These sections can later be retitled and/or reorganized to specifically match the requirements of the agency and program to which you are applying.

Most agencies will have page limits on the Project Description (10 - 15 pages is typical). Be aware of these page limits, and the strict guidelines concerning font size, type density, and margin widths that the specific agency specifies in their guidelines. If you do not follow these guidelines to the letter, your proposal may be rejected without review!

Typically, the page limits for the Project Description do not include the section entitled "References/literature cited". I usually prepare the latter section as a separate document and build this document alongside the Project Description, giving each reference a specific numeral that is cited within the Project Description. Plan to give approximately equal space to the "Introduction/background/literature review" section, and the "Experimental plan or experimental approach, including expected outcomes" section of your proposal. Many proposals are rejected because they are imbalanced. For example, they may have an excellent literature review/background, but lack sufficient development of the "Experimental plan or experimental approach" section.

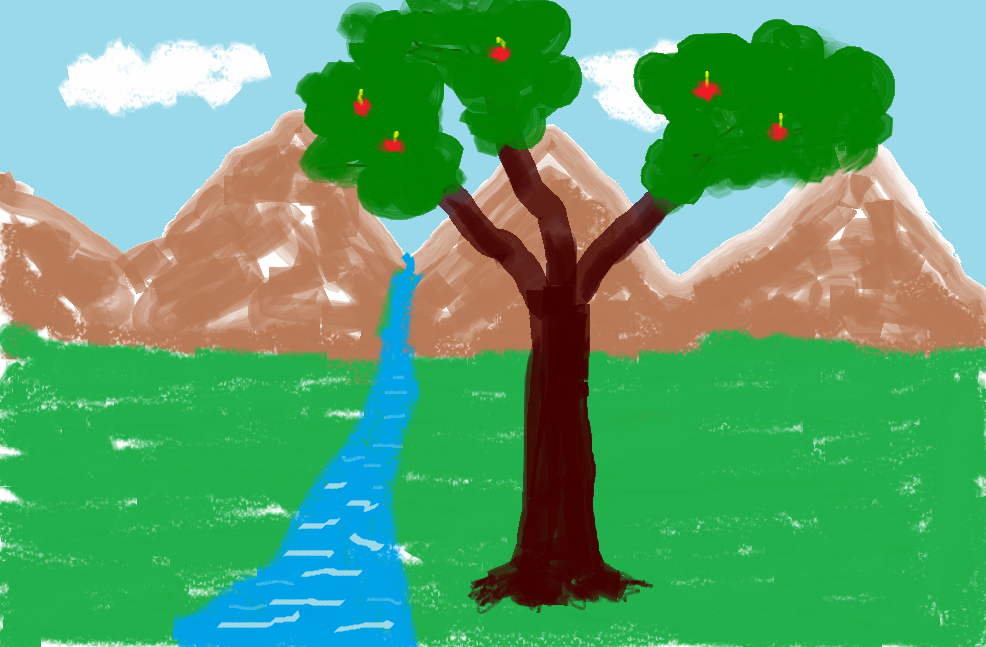

For the students in my "Grants and Grantsmanship" class, I used to draw the following crude image on the blackboard during class as a graphical representation of how to develop their Project Description: a fruiting tree on a grassy plain by a stream flowing from distant mountains. The mountains, sky and grassy plain represent the background of the proposal, with a stream of literature flowing from this background. Each ripple in the stream represents a key reference. Your proposal (represented by the tree) draws nourishment and water from this stream of literature. The central trunk of the tree represents your central hypothesis, and the branches of the tree represent sub-hypotheses and/or specific objectives or aims (1 objective/aim is too few, 5 objectives/aims is too many, 3 is optimal). The foliage represents the details of the experimental plan/approach around each objective/aim. The fruit of the tree represents the expected outcomes of your proposed research:

As you put this picture into your own words, try to follow these simple rules:

Use short, succinct, clear sentences that are free of typographical errors.

Avoid excessive use of abbreviations. For many scientific proposals some abbreviations are necessary, but excessive use can often overwhelm the reviewer's ability to keep track of their meaning.

As you are writing, ask yourself, will the reviewer be able to understand my logic?

Where possible, use figures with clear figure legends to convey complex concepts. A picture can be worth a thousand words! Use of illustrations tends to break up dense sections of text and makes the document more readable for the reviewer(s).

Break long sections of text within each section into sub-sections with discrete headings. This again aids in readability.

Bold your hypothesis/hypotheses and any feature of the proposal that is new/novel/innovative. This will help draw the attention of the reviewer(s) to these features. Many proposals are rejected because they have no novelty, and appear to the reviewer(s) to be repetitions of what has already been accomplished by others. A scientific proposal lacking a central hypothesis or hypotheses is often not successful (here there are a few notable exceptions, such as hypothesis-free genome-wide association studies (GWAS)). If your proposal lacks a specific hypothesis/hypotheses, make sure that the questions that you are asking are clearly articulated.

Some proposals are criticized and rejected because they appear to the reviewers to be "a technique searching for a problem". The principal investigator (PI) may have a great (cool) technique but they are not using it to address good scientific questions.

In your rationale and significance section, point out the relevance of your proposed research to the mission of the granting agency and the specific priorities of the program to which you are applying.

Make sure that you are citing the most recent literature on the subject. The authors of this literature may well be the reviewer's of your proposal.

In your experimental plan/approach section, give sufficient information that the reviewer can understand your experimental design, including methods to be employed (these methods can be cited in the literature review section if they are already published), use of appropriate controls, statistical analyses to be employed, etc.

Be aware that your proposed experiments under each objective/aim may have 2 possible outcomes, one confirming your hypothesis (positive) or one rejecting your hypothesis (negative). If your second and third ojectives rely only upon a positive result in the first objective, then you have a problem of "contingent aims". To avoid development of "contingent aims" (a feature that often results in proposal rejection), set up your second and third objectives to address both possible outcomes of the first objective/aim.

Be aware of how long it may take to achieve each objective/aim, what personnel may be required, and what equipment may be needed. Incorporate this into your budget and budget justification. If necessary equipment is not available at your institution, consider adding that equipment to your budget request, or arrange to collaborate with someone at a different institution, and request a letter from that individual to append to your proposal, stating that they are willing to host you. The latter applies also if you are proposing to use methods/techniques that you have no direct experience with. Seek a collaborator (an expert in the field) who is willing to host and train you!

Your proposal may not solve all of the questions that you have. That is O.K. If it takes steps towards moving the field forward and towards your long-range goals, that is satisfactory. Many proposals are rejected because they are over-ambitious, and some for being under-ambitious. It is a delicate balance to achieve the middle ground. The best proposals are the ones that will achieve significant advances, even though they may not solve the entire problem. It is O.K. to be realistic and to articulate that final solution of the problem that you are addressing may be beyond the scope of the present proposal. Some proposals are rejected because they appear to be dead-end (i.e. have no long-range goal beyond the scope of the proposal).

If you have preliminary data which bolsters your central hypothesis and supports your rationale, don't hesitate to include it.

As you develop your experimental plan, be prepared to revise your ojectives accordingly, both in the Project Summary and Project Description. As you develop this plan, think carefully about potential outcomes and potential pitfalls. Develop alternative strategies if these pitfalls are encountered. The section "Potential pitfalls and alternative strategies" will convey to the reviewer that you have thought critically about these issues.

Use a consistent format for your references, and make sure that each reference is cited in the Project Description. Use of numerals for each reference can conserve space in the Project Description.

Your proposal should seek to incorporate both good science and clarity.

If you are planning to submit your proposal to NSF incorporate a "Broader Impacts" statement [I will discuss this further in Part 3].

Have your first draft of your Project Summary and Project Description reviewed by colleagues and friends

It is essential that you seek input on the first draft of your Project Summary and Project Description from your colleagues, peers and friends. Have at least one person with extensive experience in grant writing (e.g. your mentor or major professor) review your proposal. Have at least one of your peers at your institution also review the proposal. The latter may not be as familiar with the subject matter and methodology as your mentor or major professor, but may be able to contribute to editing your proposal to achieve better sentence structure, grammar, spelling etc. They may also be able to identify areas that lack clarity or have poor logic. A friend may also be able to point out aspects or features of the proposal that need further explanation to be understandable to the lay-person.

Please allow a couple of weeks for feedback on your first draft of your Project Description, and then a further two weeks for incorporation of their suggestions for improvements and editorial changes into your second draft, paying more attention to the exact formatting and flow of your proposal in the context of the agency guidelines. At this point, you should have a solid second draft in place about 4 weeks before the proposal submission deadline. Also consider having your second draft reviewed by colleagues/peers.

Keep in mind the following characteristics of good and poor proposals. These itemized lists were compiled after consultation with Program Directors at USDA, NSF and DOE:

Characteristics of a good grant proposal

- It should have new/novel/innovative ideas.

- It should be likely to advance an area of science.

- It should fill critical gaps in knowledge of a specific area.

- It should be "science-driven".

- It should be working toward a long-term goal.

- It should have a thoughtful and up-to-date literature review.

- It should have well stated questions or hypotheses.

- Where possible it should have preliminary data which support the feasibility of the research proposal.

- It should be well written and succinct and follow the program guidelines.

- It should be relevant to the mission of the granting agency and funding priorities of the program.

Characteristics of poor grant proposals

- Proposed research has already been done by others.

- Derivative research (research may be viewed as a repetition of what has already been accomplished in other systems).

- Contingent aims.

- Dead-end research.

- Technique searching for a problem.

- Poor justification.

- PI or PIs lack necessary technical expertise.

- Not using the most direct approach.

- Wrong choice of experimental system.

- Too broad and overly ambitious.

- Too narrow in scope.

- No preliminary data.

- Lacks sufficient details for adequate evaluation.

- Poorly written and presented.

- For NSF: lack of "Broader impacts" statement.

As before, please feel free to post comments or questions in the comments section below. I will attempt to answer them as soon as possible. My next installment in this series (Part 3) will be on preparing the curriculum vitae, preparing a budget and budget justification, completing certification forms, cover page, facilities and equipment page, current and pending support page, data management plan, broader impact statement, and incorporation of letters of support from collaborators.

Looking forward to putting these tips into action! Do you have any experiences with software such as Scrivener for the writing and/or EndNote for the citations? I find Word too difficult for documents as complex as these.

I have no experience with Scrivener. I have mostly used Word. I did try Endnote, but found that it was not very consistent in formatting references when interfaced with Word. However, Endnote was (and still is) a great platform for cataloging references.

Keeping such lengthy documents in Word seems cumbersome for my brain, especially as we go into documents with many different sections. But that could also be because I have not yet used the indexing function enough. Scrivener is pretty inexpensive, so I am going to give it a try.

EndNote looks fantastic, especially since I have folders filled with people I would like to cite from for grants and research papers. The only problem is the expense right now. I am crowdfunding a computer and external hard drive for my research team (ah the joys of fundless first research projects!), and if there is anything left over, we plan to buy GraphPad Prism and the audio software needed for the study. Hopefully, I will find a good deal on the computer and squeeze out enough for EndNote, which will help the whole team!

I have given Scrivener a try - I love it for solo-writing fiction, but there's too much of a workflow mismatch between how it works best and how collaborative manuscript writing works.

For reference managers, especially if you're on a budget, I would suggest looking into either Mendeley or Qiqqa. I've used both (Mendeley currently) and either is great.

Many thanks for your input here. This may be of great assistance to others reading these posts.

Thank you so much @effofex, all feedback is useful. I was hoping it would help me organize my thoughts a little better, especially if there are many sections to a particular paper or grant. I hadn't thought about yet about the collaborative aspects.

I will definitely check out Mendeley, because even with my student discount, EndNote is still pricey. I don't mind spending money on a good product. They seem to have a 30-day trial, so I am going to try it and Mendeley to see which one I like better.

Scrivener is good for organizing thoughts, and it'd be nice if there was something similar in word. The closest I've found within the software is using outline mode to collapse and move paragraphs around.

Outside of the software, I'm a fan of synthesis matrices.

Another new technique for me, thank you! I will definitely check it out.