Experimenting With The BOGO 3.0 Business Model

Wise words on the perils of willful ignorance have come down to us through the ages from some of our best minds.

“We are all born ignorant, but one must work hard to remain stupid.”

-Benjamin Franklin

“The hardest thing to explain is the glaringly evident which everybody has decided not to see.”

-Ayn Rand in The Fountainhead

“An age is called Dark, not because the light fails to shine, but because people refuse to see it.”

-James A Michener

The last one there resonates most strongly with me. I see us as surrounded by mini-Dark ages all the time. Places where light is shining, but people refuse to look.

My experimentation in Miiru with this Buy-One-Give-One 3.0 (BOGO 3.0) business model comes from this view point and my own inability to continue to turn my head from the problems I saw everyday while travelling in Asia and South America. For a quick recap of BOGO 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 go to my last entry Why This Business and scroll to the bottom.

I could no longer walk down the torn gravel roads and rust colored back-alleys of developing countries and pass by another street vendor wondering how he would ever get his products in front of a real audience. Or watch another 14 year old breaking rocks on the side of the road without my inner voice screaming at me “SOMEONE is going to solve this, SOMETIME.” Marketplaces are launched every day. Mothers start businesses all the time, enabling their children to go back to school. Saying “someone” is easy to live with. Unless of course, when you put your head on the pillow at night you feel uneasy and unreasonable.

My breaking point came bouncing down a devastated highway in Nepal. Winding my way to from Kathmandu to Pokhara, wedged into the back corner seat of a packed 16 passenger mini-bus. Cool enough to take the $5 local bus just for fun and cool enough to sit right over the wheel wells. But not nearly cool enough to avoid the near-complete mental breakdown that loomed up ahead of us on this road trip.

As the van screamed along the mangled highway, twisting along narrow cliff edges and smashing into every pothole and crater along the dirt shoulder. Each bump would send us flying into the roof, smashing our heads before returning you not-so-gingerly onto your beaten up seat, followed by backpacks slamming down onto our laps. Add to that, sitting on the oncoming traffic side of the van as buses that are two or three times your van’s size come barreling around a curve towards you turning away at the last moment, barely a couple hands-lengths away from you and bidding your farewell with a cheerful bee-de-lee-boo-de-lee of their horn. I will never forget the sound of these Tata truck horns. Like a 1-Up soundbite from Mario was bugled through a Woody Allen auto-tuner made from an elephants trunk Listen here Rinse, repeat for 6 hours and you have the runner-up for worst conveyance of my life. That’s right, Nepal had an even worse death march than that in store for me later in my travels. Is it any wonder I love the place?

I've discovered that when you break, it takes quite some time to re-assemble. This hell ride had drilled a question into my consciousness, but it would take a while for me to copulate any reasonable solution. I jokingly asked my guide “if all the roads in Nepal are this good?” to which he replied “Dis is the main highway! Maybe one of the best in Nepal.” And he would later confirm for me that, yes for Nepali roads, this was indeed a 7 out of 10.

My mouth was agape, staring at him waiting for any glimmer of a smirk or some tell. Tossed skyward by the bus again and my open mouth slamming down to bite chunks off my tongue and cheek. In a moment of Zen only achievable by those nearing their breaking point I asked myself “How the fuck does anything move around this country?”

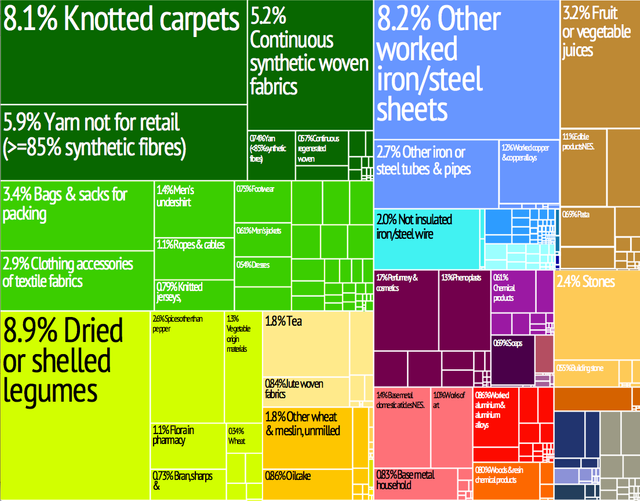

I would learn that not only is it this difficult to move anything or anyone around Nepal, it’s almost impossible to effectively export anything out of the country. Money leaving the country is a no-go. All the financial sector Nepali I’ve met with say that foreign money can flow into Nepal, but no way you’re getting Nepali money out. Trade goods falling just shy of money on the difficulty scale to export from Nepal. World Bank ranks them as the 105th overall country in Distance To Frontier, an evaluation of the ability for the world to do business with your country. Simply put; how easily can the things made around the world get into your country, and how easily can the things that your country produces get out to the world? In Nepal, the answer is not good. Another consequence of poor infrastructure is that it’s not easy to produce anything. Hard to get materials to where you produce and hard to ship your finished product anywhere. So Nepal, as a largely agriculture and tourism based economy doesn’t make a whole lot of original products. But there are some brilliant young minds and young companies coming up with business models that deal with these issues (more on that later). Here’s a recent break down of Nepal’s export by product sector. If you want to work local like us, the products you seek better show up somewhere in one of these sectors.

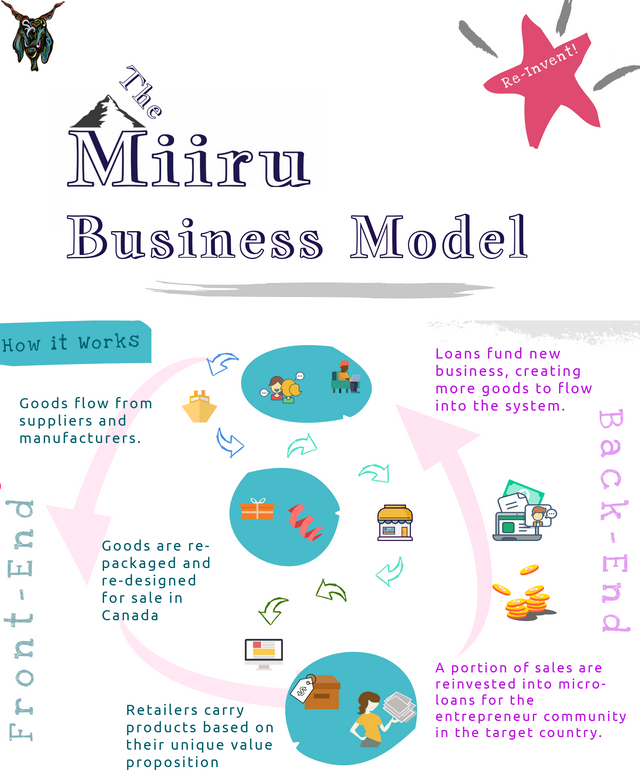

Front End:

The first piece of the puzzle is finding items produced in Nepal that will command the attention of an audience and putting them in front of that audience. Getting Nepal products into the developed marketplace.

The types of things that are easiest to find in Nepal are going to be right in your face. Store owners and vendors offer carpets, pashminas, and other textiles. Yak cheese or milk proposed every so often, available as a take-away delicacy. If you want to buy local, you have to be satisfied with what’s produced locally. What’s produced is whatever is in demand. In most cases, demand doesn’t start as a great downpour, but as a trickle from the tiny reservoir of early adopters. But demand, just like water has a proclivity to follow a course. And a babbling brook can become a raging river if fed and cultivated from the right sources.

Miiru is in the business of supplying hobbyists in the crafting market. So in my case the finished products aimed at tourists are not what I’m looking for. While too long to include here, the story of finding my first cotton and wool products in Nepal would take me weeks of searching. But the single most helpful thing was that the picture in my head of what I was looking for was clear. Textiles from a local business. Something made in Nepal.

Back End:

The second piece of the puzzle is inextricably linked to the first. By buying something from an industry you are helping it to grow. More money flowing into an industry means more eyes on it. More eyes means businesses willing to take risks to be a part of that industry. The second part of our model is aimed at super-charging this growth cycle by providing funding for new businesses to startup within the industry. That funding must come from revenue somewhere. Of course anything you take from revenue will effect your bottom line, but we are taking the long road here, where the view is better. I believe that more companies in our industry will mean a healthier industry overall. More diversified and engaging products means stability and opportunity. Essentially, you’re only as valuable as the other companies around you.

I don't like to see things go to waste. Time, workload, food, anything really. It frustrates me when I pass by a place where people work so hard and perceive them as accomplishing relatively little. Even more frustrating when you’ve seen how insanely productive people can be in the right situations. The majority of people that I see busting their ass for $3 a day have a work ethic that would put any of my former classmates to shame. It’s not necessarily work ethic when work is a necessity. Hard work isn’t frustrating, but what is frustrating is watching someone make a quarter of the progress that they could if they were properly supplied. Resources in the wrong place. Hunger in a desert.

What I started to notice is what I call “$100 fixes”. Not an expensive band-aid where duct tape will work. But a situation where if you looked long enough at the problem you could see that a real, effective change in the trajectory of someones work could be accomplished with a small amount of the right resources. Walking by a store renovation where a power saw would make a worker 10x as productive. Seeing a mother who could stitch more than her own child's school clothes, but maybe the whole neighborhoods if she had a sewing machine.

This idea to me would become a wrecking ball to my quiet acquiescence to the rhythm of Western consumerism:

The idea that you could start someones business in this part of the world, for $100.

You could make someone’s work infinitely more rewarding to them and productive to all of us with $100. This wrecking ball kept banging around inside my head, making sure its presence was ever known with a certain pressure behind my eyes. Seemingly until I would do something about it.

Zero is a very weird number. An enigma. It provides no opportunity. You can’t do anything with zero. You have to hope that at some point zero becomes one, or some. Anyone who's lost at Monopoly can see how rapidly things can get away from you. When you hit $0, that's it. You're out. The reality is that the minimum monthly salary in Nepal is about $92 US. If you are making $92 a month, the amount of spare capital that you have lying around to fund that startup idea of yours, however simple, is effectively Zero.

Even when things start slow, they have great potential when they take off in the right direction. When that shop around the corner starts doing well as people are buying their fabrics at a fair price, the signs being to look better. Now someone funds your purchase of a sewing machine with which you can do alterations and make clothes in your neighborhood….maybe something is starting. And not only do you have your own small business, but five of your friends in town also have sewing machines on which they are making clothes, or barber kits which they are using to cut hair. Well then, that starts to look an awful lot like an economy.

Charity has it’s place. But I believe in the nobility of good work. My company was founded around the idea of being part of others journey to en-noble and sustain themselves through good work. But those journeys will cost something, as they should. If you want to live in a world where opportunities are plentiful, the right amount of your money to devote to making new opportunities isn’t zero.

Check out my few other posts on Steem @

- https://steemit.com/startup/@almostfitz/why-this-business-data-confidence-and-shit-testing

- https://steemit.com/startup/@almostfitz/why-this-business-set-your-anchors-deep

- https://steemit.com/travel/@almostfitz/tourists-pull-your-head-out-of-your-ass

- https://steemit.com/worst/@almostfitz/the-potential-freedom-in-being-the-world-s-worst-entrepreneur

- https://steemit.com/storage/@almostfitz/the-self-storage-industry-feeds-off-laziness-save-money-by-organizing

- https://steemit.com/business/@almostfitz/open-for-business-11-pictures-about-launching-a-startup-speak-11-000-words

- https://steemit.com/shark/@almostfitz/i-binged-5-seasons-of-shark-tank-and-got-something-out-of-it

- https://steemit.com/dnn/@almostfitz/dnn-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly-on-how-to-create-a-decentralized-free-news-platform

- https://steemit.com/writing/@almostfitz/free-writing-cage-that-monkey-mind-and-get-creative

- https://steemit.com/data/@almostfitz/stop-wasting-time-168-hours-tracking-system

Check out my posts on my other blog on my Shopify store @