Argument and fallacies - A small introduction into a Human trait (part 1)

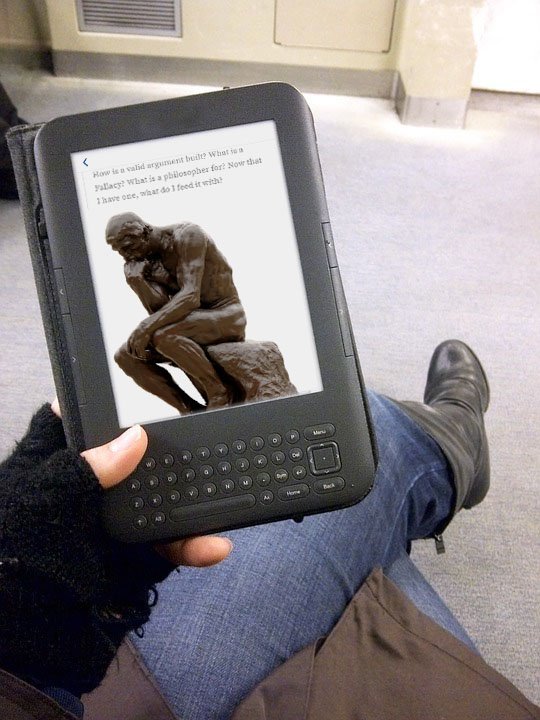

How is a valid argument built? What is a Fallacy? What is a philosopher for? Now that I have one, what do I feed it with?

Deep inside every parent's heart there's this dark nightmare lurking: What if this kid, that I unconditionally Love becomes Philosopher?

We can imagine them, her with her labor contractions, him tagging along worried, imagining a future loaded with responsibilities. Some years later, the kid has a smooth speech, unstoppable... AKA: please make him shut up!

First that little thing says single words, later sentences, and after that he learns to argue. And as an argument heats up, the inquisitive philosopher's cub notices that he can "make" his argument valid by detecting the cracks in the other one's. Those cracks where water leaks in, are known as fallacies.

Once grown up, the same cub has to face the same habits that he carefully developed, because they turn against him. It turns out that fallacies are not only useful to detect weak reasoning lines and "win" an argument, they also serve to build a GOOD reasoning line, and from that, not even him is safe. So, the little cub is faced with a horrible truth: people tend to reason in the wrong direction, and him (or her) is also "people".

Now he became brittle and in equal conditions against the world under his human condition. He no longer looks out, he becomes his own opponent in his speech, commited to never leave a crack in what he says.

Our emotions, fears and other cognitive biases tend to makes us upkeep certain beliefs, irrationally in many cases, and with us not even noticing. Learning to identify how our brain cheats on us is an experience worthy of being shared, and from that several philosophers enjoy the study of fallacies so that everyone may recognize where their reasoning lines are breaking, so that they may adapt them. After all, it is important to consider that people tend to think illogically not because they want; but because, until we look into a better option, we have no choice.

We all have the ability to establish and verify facts, change and justify beliefs, and generally speaking give a sense to what we live. This is achieve by the use of reason and the process known as reasoning. Now, while practically everyone is capable of reasoning, there's only very few able to do so in an acceptable level.

As we figure "argument" we imagine screams, attacks and negative emotions flowing back and forward. If Aristotle saw this, he'd die again, because the root of arguments is in the exchange of points of view, exploiting the use of reasoning to communicate rationally (That is why, many arguments look as if two dogs were barking at each other... They are doing it wrong). Arguments are nothing else but the attempt to persuade someone into something, giving reasons so that a determinate conclusion is accepted.

We do not need to glance too much to notice that we are constantly arguing, when we shop something, when we vote someone, when we go to a bar instead of preparing our essays. We rarely stop to look at the premises and rules that this arguments imply. And if the point of an argument is the persuasion, it is clear that the ways to persuade someone are not limited by reasoning.

Sometimes, they are rather obvious (Oh! boobs and abs! I'll buy this phone!), but some are very well concealed, nearly invisible. It is then when understanding how an argument is made vaccinates us against false premises (your love, my pain), making philosophy the last line of defense against marketing and propaganda.

An argument is formed by premises and a conclusion. Sometimes, the premises are called reasons, evidence or asseverations. Sometimes the argument is condensed in an affirmation that contains the premises and the conclusion.

On a rough sketch, there's two forms of reasoning. In one side we've the deductive arguments, where the conclusion is deducted logically off the premises. A classic example:

All men are mortal

Socrates is a man.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

When we talk about a deductive argument, if the premises are true, the conclusion also has to be. The arguments we find in math and formal logic are shaped this way.

On the other side we've the inductive arguments, where the conclusions are supported in probability rather than in logic. This arguments are generally built under inductive reasoning lines, the process where one may infer into generic conclusions off particular examples. Most scientific arguments are of this kind, we basically give them a statistically high support, but not absolute. An example:

Until today, every day the sun came out.

Therefore, tomorrow the sun will come out.

Even it is possible that the sun may burst into a supernova this night, it is very unlikely.

Neither inductive or deductive are better or worse, they both serve different knowledge branches. We can believe that with deductive arguments we never truly add information: we are always deducting from information already available. Yet, we cannot think that about science, since our data our evidence, is constantly changing and being refined.

Arguments are everywhere, and where there's arguments there's fallacies, bad reasoning lines. It is important to be able to recognize fallacies and the danger they imply. They are not easily found and they are designed to dodge us while making arguments persuasive (for the wrong reasons). As Bo Bennet said:

Fallacies are like brain mirages.-Or something like that-

We may be confused by the difference between "truth" and validity. What is true or false are the premises and conclusion, what is true is something that it corresponds with reality. Validity, instead, is a reasoning line property. An argument is only valid when the premises and conclusions match each other (not necessarily being true!). What matters in a "tale" is that the verisimilitude does not fail! This is internal coherence, not truth.

It is important to consider that fallacies point out problems in the shape of the arguments not in the veracity. A fallacy is an argument that "looks" valid but is not, many times they appear when there's not even an intention to use one (where nobody is attempting to trick anyone); that, is the worst case scenario: The belief of a correct reasoning line, the fallacy taking total control.

The importance of recognizing fallacies is not in the fact of us being able to rub others mistakes in their face, it resides in the ability of finding our own mistakes, even when we have the correct data. After all, it'd be a shame to lose an argument where our line of thought is based on true facts... because we present them in the shape of a fallacy.

To recognize them, helps us reason better. As soon as we subscribe into the Logic Gym we notice how easy it is for us to fall into the pit of a wrong reasoning and stretch a conversation when we were already at the final lap.

Fallacies are so frequent, they ruin so many arguments, that it would be smart to carry post-its with them written down. To detect them when they are used either for the sake of strategy or by mistake. A fallacy does not talk about the topic, it attacks the construct that is compromising the truth. As I read about an hour ago:

What you really meant to say was , you cant discuss survival of the fittest theory.

I was being too kind not throwing an ad hominem about his inability to paralellize two topics as a mean to explain his point of view (but his distance from truth was more than enough to even consider his premises).

In the next article I'll introduce you to some common fallacies, so that you may understand the rules of engagement in an argument. Always assuming you're arguing against an equal, both facing in the same direction: Looking for the truth. Stay tuned!

If you liked this post and its informal way of talking about sciences, please, follow me for more!

Leave a comment either for good or for bad reviews. I take everything as constructive, and I really appreciate the feedback, even from trolls (at least a troll read it before being himself!).

Copyrights:

All the previously used images are of my authory or under a CC0 license (Source: pixabay), unless openly stated.

All the Images created by me possess a WTFPL licencing and they are free to redistribute, share, copy, paste, modify, sell, crop, paste, clone in whatever way you want.

Nice work - nothing like philosophy before my first coffee ;) I liked your images as well.. I have Rodin's "Le Penseur" right here on my desk... Sometimes it feels like a caricature!

Philosophy was one of my fav classes as I was younger, mainly because it encouraged "thinking" just for the sake of doing so.

I'm glad you liked the article, thanks for your feedback.

This post has been ranked within the top 50 most undervalued posts in the first half of Dec 19. We estimate that this post is undervalued by $7.79 as compared to a scenario in which every voter had an equal say.

See the full rankings and details in The Daily Tribune: Dec 19 - Part I. You can also read about some of our methodology, data analysis and technical details in our initial post.

If you are the author and would prefer not to receive these comments, simply reply "Stop" to this comment.

Reading, Logic and Rhetoric, that is what used to be taught.

Today's schools only teach rhetoric. Here are the conclusions, memorize them and then repeat them. And! You are good person if you repeat them well, and a bad person if you don't. Thus, you end up with a person who will defend their "knowledge" as if their life depends on it.

So, most people's arguments is, "this is what I learned, and you better accept it too."

Because, people that think tend to have independent ideas that go against certain people...

I'm glad you liked the article (I was craving for some feedback)