Killer Death Rocks from Outer Space!

Steemit does not have a lot of localized content outside of travel. This is an experiment.

Last spring, March 4-5, G-tech held its fifteenth Triad StarFest. The Astronomy Department and its group of student volunteers, the Stellar Society, host free viewings at the Cline Observatory almost every clear Friday evening. These average about 50 people per night, which over the years since the observatory opened in 1997 have added up to more than 25,000 visitors. Several times a year they bring in professional astronomers for lectures and networking with the local clubs, such as the Greensboro Astronomy Club. This is unusual for a couple of reasons. Most community colleges don't emphasize research, and most university lectures are not advertised to the public. In other words, this small department is punching above its weight class. There were also tables out in the hall for a swap meet, photo contests, and raffle items to pay for the coffee and Krispy Kremes.

The overall theme this spring was asteroids. There were four speakers in the lineup.

Friday Night

J. Patrick Miller from Hardin-Simmons, a small college in Abilene, Texas led off on Friday night with a parade of the greatest hits. 1908's Tunguska was a hundred thousand tons of rock, heated by its passage through the the atmosphere until it exploded in a 10 Megaton “airburst” over the middle of nowhere in Siberia, killing noone, but knocking down a lot of trees.

A few hours later, and the earth would have rotated St. Petersburg or Oslo into the cross-hairs, and the resulting million deaths probably would have pushed asteroid science to the front of the research queue. Instead Tunguska was mostly left to the UFO community until recently. 2013's Chelyabinsk, another Russian airburst, though much smaller than Tunguska, was a darling of social media because of all the dashboard camera footage from Russian drivers. Again, noone died, but about 1500 people were injured from the glass shrapnel of exploding windows and collapsing buildings. Astronomers used all that free video to reconstruct the explosion in computer models and determined that Chelyabinsk was about 60 feet across and weighed maybe ten thousand tons. Dr. Miller has taken up that crowdsourcing strategy, and now has kids in 500 different schools around the world searching archived telescope photos for asteroids. They've found about twelve hundred so far, including two that could threaten the Earth.

Saturday Morning

These two speakers departed from the theme. Peter Prendergast, a Kernersville MD in a daffodil-yellow shirt, brought the crowd down a little while he played the “I built my own remote-controlled telescope” blues, detailing the trials and tribulations of the amateur astronomer, who pays for equipment out of his own pockets. Apparently, it's a lot like owning a boat.

Then Brad Barlow from High Point University, a relative newcomer to the Triad science scene, rocked the house with his discoveries that when stars like our yellow sun run low on fuel and expand into “fluffy” red giants their orbiting companions, whether they are smaller stars or really big planets, don't always just burn up. Instead they can strip away the parent star's atmosphere, leaving behind a hot blue dwarf star and a nebula. These clouds of glowing gas are the colored backgrounds that have become so popular in space photos, and several of the amateurs in the crowd had submitted photos of nebulae for the “people’s choice” contest.

Saturday afternoon

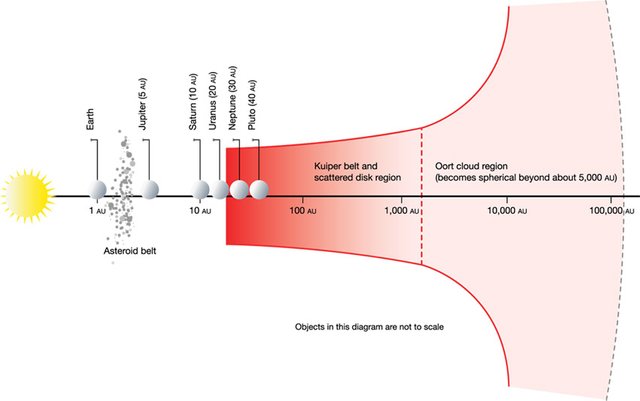

After lunch, Patrick Miller returned for another set. This time he focused on a tour of the three big reservoirs of space rocks. The Asteroid Belt out between Mars and Jupiter has a large number of small rocks and a small number of really big rocks. A few of them, like Ceres and Vesta, are so big that gravity squeezes them into spheres, so that they look like miniature planets instead of those crusty, irregular things from the chase scenes in The Empire Strikes Back. The Kuiper Belt, out past the orbit of Neptune, holds Pluto and billions of other icy rocks. At least 5 of those are as big or bigger than Pluto, although noone argues that any of them are planets. And then there's the Oort Cloud, another source of icy rocks that sometimes come screaming into the inner part of the solar system, where we are, as comets. The Oort Cloud is way out there, extending perhaps a third of the way to the nearest star.

Finally, Mike Solontoi, the hardest working man in star business, hit the stage in his suspenders and red tennies. The other speakers had all been more or less dignified in their approach, but Solontoi bounced around, talking fast, doing a handstand in front of the screen, and apologizing whenever he had to show a graph. Given that it was already about 3 in the afternoon, and given that GTCC is a dry campus, where you can't take a beer into the auditorium, this was not a bad thing. He reprised some of the greatest hits discussed by Dr. Miller, but spent more time on the “behind the music” dynamics of exactly how the dueling gravities of Jupiter and Saturn tug asteroids out of their nice, safe solar orbits into ones that will either dump them into the sun, fling them out into the Oort Cloud, or eventually smack into one of the other planets. Like the Kline observatory's impressive crowd numbers, small gravity bumps add up over time. The last really big asteroid to hit the Earth, about the size of Mt. Everest, took out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago and left a 120-mile wide crater off the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

[This is actually from a similar talk a year ago, but the image (via the Pulp-O-Mizer) was so great I'm using it anyway]

We don't know when the next big one will be, partly because (as a look at @lowflyingrocks on Twitter will reveal), we often only see them after they've already passed us by. According to Solontoi, these rocks are “about as reflective as a charcoal briquette.” Without the water ice that evaporates into the glowing tail that we associate with comets, asteroids are really hard to see against the black background of space, especially with all those pesky glowing stars distracting us all the time. Dr. S. also pointed out that a much cheaper and more effective way of deflecting an oncoming asteroid is not to blow it up, a la Michael Bey, but to paint it. Changing the color will change the way the asteroid absorbs sunlight. In space, the small amount of heat radiated back off the asteroid acts as thrust, which over time could nudge the asteroid off its collision course.

http://www.space.com/19905-dangerous-asteroid-deflection-paint.html

The next event in the Titans' astronomy series will be on September 23rdnd, when Harvard astronomy professor David Charbonneau will talk about finding exoplanets by looking for signatures of life in their atmospheres. I will have to miss that lecture, as I will be at Clemson for this conference. Would probably make a fascinating Steemit post ...

In the meantime, the dome is open on the Cline Observatory almost every Friday night. Check http://observatory.gtcc.edu/public-viewing-schedule/ for details.

With physicist Diedrich Schmidt, your friendly neighborhood neuroscientist Randall Hayes hosts the monthly Greensboro Science Cafe discussion group at Scuppernong Books in downtown Greensboro. This month geology major Shawn Fitzmaurice will be on hand to discuss his SciWorks Radio segments. For that date, and their full schedule, see facebook.com/greensborosciencecafe.

You know.

We're kinda lucky.

What would have happened during the "cold war" if Chelyabinsk, had happened then?

Nuther question. How often do big rocks like that hit earth? How many hiroshima (a few kilotons) sized explosions are likely to happen due to meteor impact that we don't know about? Two thirds of the earth is covered by water, after all.

Well, there was this, which (according to a US Air Force general) mighta coulda been mistaken for something hostile by either Pakistan or India, if it had happened slightly later.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2002_Eastern_Mediterranean_event

And here's a map of all the impacts from 1m to 20m (Chelyabinsk being the biggest) over about the past 20 years.

http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/CosmoSparks/Nov14/meteormap+meteorites.html

And some further commentary

http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news186.html