The Perils of Playing God: Why Geoengineering is Profoundly Dangerous.

@pathforger recently wrote a post on how we could terraform the Sahara desert into an inhabitable garden. It's a pretty well researched, interesting, and well written post. And I hate to be a Debbie Downer, it's also an extraordinarily bad idea.

First off, deserts are important parts of the global climate system. Eliminating the desert in the way discussed would produce a brand new moisture upwelling zone in the middle of Africa, likely resulting in the formation of new deserts elsewhere, as well as truly catastrophic weather patterns as the planet adjusted.

That's not the only problem, either- it would be catastrophic to the Amazon rainforest, which is heavily dependent upon nutrients in the form of dust carried to it on the wind from the Sahara. That massive expanse of unconsolidated sediment that is the Sahara is essential for the survival of the imperiled rain forest, which is the single most important land biome for global weather stability and biodiversity.

That's still not the last problem- there are countless species that only live in the Sahara, and transforming it into a garden would drive many of these delicate drought adapted species extinct.

Hell, on top of that, there are people living in the Sahara by choice, just like their ancestors for countless generations before them. I can't imagine that many of them would be extremely fond of the plan.

I can keep listing reasons for a while, but it boils down to a fundamental principle: Forcing the Earth to conform to our desires rather than adapting to the conditions of the Earth is a profoundly risky task that results in unforeseen and often catastrophic environmental, ecological, economical, and social consequences.

Let's take a look at some past attempts at geoengineering that have actually got off the ground.

First off, we have the great tree farms of 1800s Germany. They were adored by intellectuals at the time as masterful works of scientific agriculture and planning. They featured neat rows sorted by tree type, no undergrowth getting in the way, and clearly surveyed boundaries. They were orderly and easy to tend and harvest. And, indeed, their output was much higher than that of actual forests- at first. Within a few short years, however, productivity began dropping and dropping and dropping, until many of the tree farms were running at a loss. The planners had completely failed to understand that the health of the forest was massively dependent on the complex ecosystem it sustained and lived in- and without it, their project was doomed to failure. There were also harmful social consequences of the projects. The forests that the farms had replaced had been used by local villagers to support themselves since medieval times and before. Pigs were herded in the forests to eat acorns and mushrooms. Coppicing and the gathering of downed branches provided firewood for the forests. Small game provided much needed protein in the villagers' diets. Without the forests, the economic situation of the villagers rapidly worsened, resulting in mass migrations to cities and even the Americas, as well as rampant poverty and vagrancy.

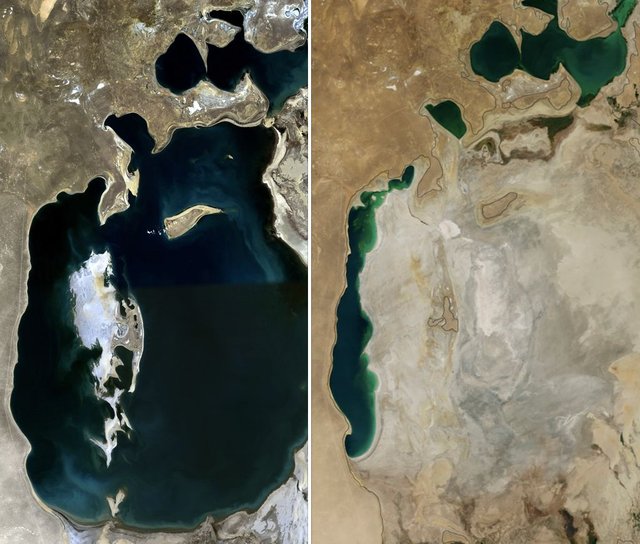

Next let's take a look at the Aral Sea. Or, rather, we won't, because it doesn't exist anymore. It's gone. Kaput. Why? Well, almost entirely due to the rivers feeding it being diverted for a series of wasteful large-scale agricultural projects by the Soviet Union now being maintained by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. This was an attempt to geoengineer the area to make it a viable cotton producing region. And, again, it worked for a while- but it's not so successful today. The vanishing of the Aral Sea has also resulted in the loss of jobs and traditional livelihoods for all of those who lived on the shore. As if that weren't bad enough, the years of industry and agriculture before the draining of the sea filled the seafloor sediments with fertilizer, pesticides, industrial contaminants, nuclear waste, and more nasty stuff. Now the exposed toxic dust is being blown hundreds of miles, causing an epidemic of cancer, poisoning, birth deformities, and other chronic health problems.

The Mississippi River has been drying to escape into the Atchafalaya River for around a century now. The dedicated efforts of the Army Corps of Engineers are the only thing standing in its way, because if the Mississippi diverts, New Orleans will wither and die- along with one of the single most productive industrial zones on the planet lining the banks of the Mississippi below the Atchafalaya. But, because of their efforts, as well as the dredging necessary to keep the channel clean, the huge marshlands that bordered the Louisiana delta and protected it from storm surges are rapidly eroding away, leaving the state severely vulnerable to hurricanes. On top of that, without the constant sediment flow to keep rebuilding the delta, the whole thing is sinking into the Gulf of Mexico.

There are a lot of geoengineering plans to save us from global warming. One involves dumping powdered iron in the Antarctic Ocean to make it more of a carbon sink. It would actually solve the problem- but it also very well might sterilize the oceans. Another involves injecting light deflecting particles into the atmosphere to reduce incoming solar radiation. This could not only have disastrous effects on global weather patterns, including causing a deadly drought in the Sahel savanna in Africa and potentially suppressing the absolutely vital summer monsoons in the Indian Ocean, without which India would be uninhabitable. (Millions typically die in any year when the monsoons fail.) It would potentially do immense harm to numerous plant and animal species that are extremely dependent on sunlight. And to add insult to injury, it would make ground based astronomy nearly impossible.

I can keep going on for literally hours. LA's constructions in landslide zones. The attempts to practice European style agriculture on the American Great Plains that led to the Dust Bowl. The degrading Nile River Delta due to the Aswan Dam. Immense geoengineering projects are dangerous and unpredictable. It is by far better to live by adapting TO nature, by treading as lightly as we can, and by doing our damned best to understand the ecosystems we live in.

.......................................................................................

If you're particularly interested in the dangers and difficulties of geoengineering, I highly recommend starting learning about them by reading both John McPhee's The Control of Nature and James C. Scott's Seeing Like A State. The latter, thicker work also covers a number of utopian social projects, as well as discussing the philosophies that are so often behind them and geoengineering.

Thanks to @pathforger for inspiring me to write this post (nothing more motivating for me than wanting to argue) and for doing some good research into the techniques necessary to geoengineer the Sahara, even if it is a bad idea.

@mountainwashere

a true great posts... which reminds me of Michael Jacksons "Earth song" Modernity and high tech engineering is causing more harm than good to the worlds eco system... such posts brings us back to reality... thanks for sharing a post truly worthy of my upvote

It's true, and yet it's also essential to sustaining the lives of billions of people. I don't feel morally capable of deciding who gets to live and die, nor do I trust anyone else to do so, and so we need to maintain our technological civilization to sustain humanity. It leaves us a very fine line to walk on- how do we preserve humanity while minimizing harm to the environment? There's not a lot in the way of easy answers there.

sure... seems the world is progressing badly in areas of war fare... what north korea is doing is a sign of bad omen to come! I pray the super powers considers the people living in the world and its environment before all these high tech war fare... it reminds me of also sustainability through going natural in our eating habits... little wonder i post a lot on such and will do more... seems we have similar mindset... find time to check out some of my blog posts as i do expect your well informed comments...

He'll be wanting to grow tomatoes on the moon next! You may possibly get some scrubby dusty fields out of the plan but I prefer the one in your picture. Learning to manage waste on this planet is the answer, including urban food waste and too many cars. JV

Oh, I've got to admit, I'm a huge advocate of space development- in no small part because a single decent sized metallic asteroid could fuel the Earth's demand for metal for several years, obviating the need for destructive and toxic mining of the Earth's crust. Other reasons as well.

But yeah, we need to seriously learn to manage our waste and our resource overconsumption on this planet as well.

If we sensibly look after what we have already we won't need other planets. No problem with space travel - I saw the first moon landing! JV

For me it's more a combination of risk mitigation (not keeping our eggs all in one basket) and a need to explore.

Very sensible. Stick to it!

Growing crops in space does sound like a fascinating proposition, actually. ^_^

I have to admit though that, as much as I really like the idea of terraforming other planets (once confirmed that there are no species being killed off as a result), I also am highly sceptical of humanity's maturity and readiness to do so. Lets try and get it right here first.

Besides...

Source

Absolutely!

Well @mountainwashere, you have done an admirable job of one-upping me on this subject. :c) Well done, both for your writing and your research - and thank you kindly also for the mentions. ^_^

There are a few aspect where I'm sure you're fine with me pushing back on however (and I'll keep my points brief so as not to be tempted to turn it into a post (two-thumbs up by the way). ^_^

First things first however. You are stimulating discussion, and not merely being "a Debbie Downer". You're cool. ;c)

I am aware that desert, and especially Savannah, is able to sustain the livelihoods of a fair few species. That being said, considering that the Sahara desert alone is comparable in size to the entirety of the United States of America, I would posit the notion that diminishing the boundaries of the Sahara would leave plenty enough area for those species to thrive in regardless.

Human understanding of managed forestation projects has improved since the incidents that you mentioned. I was personally thinking that a casual approach of 'pass the water and the vegetation will come' would be one way of allowing nature to decide on how to best make use of the new inroads of water supply. That being said, it may well be desired for food crops also to feed off of such sources.

I quite agree that a significant impact upon weather in the vicinity may be noted. That moisture will feed weather systems. That being said, I don't think we'll be seeing typhoons any time soon - since these require far bigger bodies of water to build the required strength. More likely are drizzles or rains hundred of miles away fed by the evaporation.

I personally disagree that shifting the land status from desert to Savannah or greener would trigger other places to become deserts. We are not talking of rerouting rivers to figuratively rob Paul to pay Saul (as per the Aral Sea). We are talking of tapping into a big source of water (initially the Mediterranean Sea) to artificially hydrate that which would otherwise be further prone to desertification. I also suspect that the dust needs of the Amazon forest would either be met well enough by half the Sahara desert's present size - and if not - that an alternative could be found either by humanity or the forest's own adaptation.

In spite of sall these differences in perspective, I would certainly agree that geoengineering is a 'potentially' hazardous practice. The degree to which this is so may be measure both in terms of the aims of a given project as well as in terms of the level of understanding of the leadership concerned.

I think that I've covered the main points that I wished to cover. :c) Again, thank you for stimulating discussion - whether it be on my post or a post of your own. Your cautioning is warranted - but I also feel that the possibilities equally warrant exploration.

They definitely do warrant exploring- there have been some successful cases of geoengineering in the past, most notably the Dutch lowlands and the Native American methods of forestry management. There's a commonality between these and the other successful instances of it- it's done very, very cautiously, with ample knowledge of the function of the environment around them,an awareness that it takes constant effort to maintain, and a willingness to nudge nature in a new direction rather than trying to wrestle it whenever possible. It's also generally safer to perform said nudges in more robust ecosystems like temperate old growth forests, rather than more delicate ones like deserts. Overall, though, the failure rate for geoengineering projects is extremely high in the long term- unfortunately, however, we aren't very good as a species at thinking in the lomg term, and short term success is extremely attractive.

Very good points made throughout @mountainwashere. :c)

The truth is that the success or otherwise of a project tends to be measured through human-centric metrics. Would certain aforementioned forestation projects have been deemed a failure had there not been a drop-off in land productivity over a few years? The answer would likely have been in the negative.

A departure from such human-centricity permits a more holistic approach better-compatible with the ways of the Native Americans and others who remained spiritually close to the lands upon which they lived.

In the relative absence of such an affinity one would indeed need to engage the environment with caution and knowledge (the latter only coming about through drawing upon that which has been tried and through progressive experimentation).

And through beginning with a single project in, say, Algeria one would be indulging in that spirit of experimentation and learning that would constitute less of a shove and more of a nudge in the context of the entire Sahara (and there would be plenty of Sahara remaining for species encountering hardship from those nudges to retreat into).

You are very correct in noting that humans are better at thinking short term than long term. We want gratification. We want it now. It drives our decision making process - often enough to ruinous ends.

However one should also recognize that the story of humanity's journey toward achieving flight was strewn with failures and learning before the first rays of success led to a continuing era where commercial flight has grown to be the norm.

Amazing!!! Very very wonderful!!! ilike it and upvoted ;)

Thanks!

Upvoted and also resteemed :]

Awesome, thanks!

Very nice post buddy I really like it and appreciate your hard work

Thanks, I'm glad you enjoyed it!

I read the post you are responding to, and I didn't agree with the idea on principle; however, I didn't wasn't aware of the evidence against it. You made a very strong, data driven argument. Very nice!

Thank you, I'm glad you like it!

@mountainwashere another great article! It's amazing how individual ecosystems have balances to maintain homeostasis, and it scales up everywhere! Our planet has different regions and climates for a reason, it makes sense that there would be ramifications for messing with that. Good point with the increased moisture upwelling in Africa (hello new flooding problems) and a new desert popping up somewhere else. The balances to keep our planet habitable for us extends our into our solar system and beyond. We start messing with that and it may screw up the reasons life can be sustained here in the first place.

Interesting ideas you shared about ideas to counteract global warming; I hadn't heard of these. A sterile ocean, depriving plants from what they need from the sun, and no more surface based astronomy? But I enjoy amature astronomy! It's a fascinating world we live in, and we have the responsibility and gift of being good stewards of it. That's certainly becoming a more challenging thing as technology advances (more so in reference to past technology; this is going in a better direction now) and populations increase.

We can interfere with the natural world successfully- but only with caution, and only with great knowledge of the environment. Nature can form a new balance, a new homeostasis- but we might not like where it ends up.

Absolutely. Well said.

Congratulations @mountainwashere! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPgeo engineering is fantasy.

it does not exist.

...As a geology student and historian, I can absolutely tell you that yes, yes it does exist, and has been practiced on a large scale before. I give several examples in this post which you apparently read in a little over a minute. Perhaps you're thinking of terraforming on a planetary scale, which we haven't done yet?

I'm a fast reader...1K words a minute.

don't care what the text said...geo-engineering isn't possible.

I'm a retired trucker...we're never wrong.

I can't tell if you're being serious or not. If so, would you care to offer some sort of argument about why it doesn't exist, rather than a blanket denial? And the text of this post, by the way, is me writing- if you're going to say you don't care what I have to say, please do so outright, not in such a roundabout fashion.

energy.

consider a boy pissing into a hurricane..

how's that working out? Affect it much?

same thing with humans effect on the environment.

...

am I serious or not?

who knows...I certainly don't.

I do care what you have to say...

but since you post it...it's fair game.

Now we're getting into the complex systems, one of my favorite topics!

Yeah, the amount of energy we exert on the system is relatively small compared to the total energy in the system- but what matters is how and where it is applied. Complex systems like nature are pretty resilient to major shocks to the system- but gradual applications of energy in the long term can have huge consequences. The Fertile Crescent, for example, is largely a desert wasteland today, where it used to be a veritable garden. This massive change was the result of the ancient Mesopotamians over-irrigating their land, resulting in the deposition of large amounts of salt into the soil, shifting much of it into inhospitable desert. And all it took was the relatively small amount of energy that it took to dig and maintain some irrigation ditches.

It's basically like rolling a snowball down the mountain. You only put in a tiny bit of work, but the snowball ends up as a massive destructive wrecking ball. Or like how putting weight on a really long lever can move huge objects. It doesn't take that much energy to cause these changes.

It should also be noted that said changes are really, really hard to stop once they start. Hurricanes are changes in the system that have begun snowballing- that's why they're so powerful and hard to change.

That might or might NOT be the case...I've heard alternate explanations as to why north africa is a desert. I've also heard that the Amazon Basin is was an artifact (1491) during that same time frame...

You're not going to start talking about butterfly sneezes are you?

The Amazon Basin was heavily affected by human activity, yes- (I'm assuming you're talking about the manmade terra preta soil) but the Amazon rainforest itself long predates human activity in the Americas.