From Simplistic Assumptions to Sensational ‘Scientific’ Results

Is Life Fragile, or Tough?

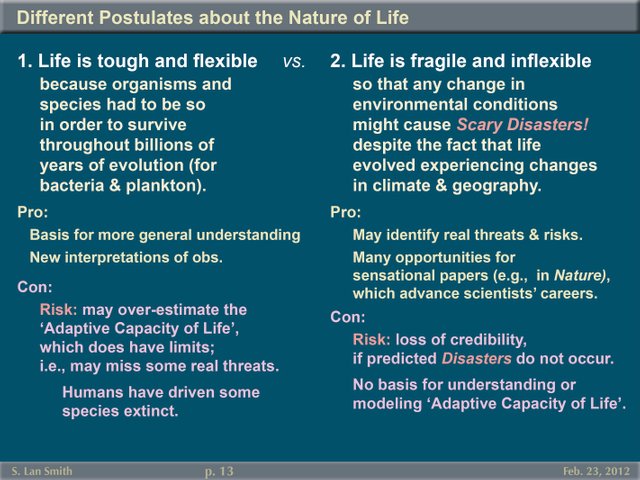

In my previous post I included the following slide with two quite different postulates (basic assumptions) about the nature of life. More specific assumptions are required for studies of biology and ecology, whether by analyzing data from observations (as in the example below) or by constructing and applying mathematical models as I do. Whether purposefully or not, the individual making those assumptions does so based on some postulate between these two extremes:

I showed the extremes to make clear their contrast, and acknowledged that most people do not go fully, at least not consciously, to either extreme. One of my goals was to challenge the use of simplistic assumptions to generate (intentionally or not) sensational results portending doom.

Individual Organisms are Fragile, Species and Ecosystems are Tough

Although individual organisms can be quite fragile, species and ecosystems can be very resilient, and even Antifragile. That resilience is in fact largely the result of the fragility of individuals. Natural selection can only operate if some successfully reproduce while others do not.

An Example of Simplistic Assumptions yielding very Sensational, and Quite Incorrect, Results

It really does happen, as this example shows. Boyce et al. (Nature, 2010) had gotten a paper published in probably the most high profile of all scientific journals, in which they had “estimate[d] a global rate of decline of, 1% of the global median per year” for phytoplankton biomass over the past century. That implies that present-day phytoplankton biomass would be only roughly half what it was 100 years ago! (There’s a more subtle problem, too, with how they expressed that rate of change relative to the concentration, but it’s a minor point compared to what follows).

They obtained that result by assuming that chlorophyll concentration is a good proxy for the biomass and productivity of phytoplankton (algae that move freely with the water), and by further assuming that the attenuation of light in the water is a good proxy for chlorophyll concentration. Neither of those assumptions is very well founded. Three groups of authors soon published comments focusing on the statistical methods and the fact that most of the data they used were not direct measurements of chlorophyll, but merely a proxy based on how light was attenuated in the water. Those were valid points. Here I’ll address what I believe is the more fundamental, and even more flawed, assumption.

Evidence Ignored

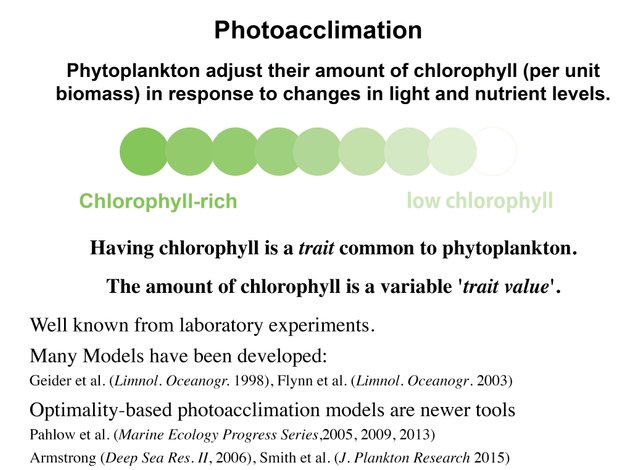

Boyce et al. (2010) in effect assumed that the chlorophyll content of phytoplankton (relative to their total carbon biomass) remains constant as environmental conditions change. This is quite relevant, because they also attribute their estimated decline of phytoplankton to global warming and associated reduction in mixing near the ocean’s surface. However, chlorophyll is not a good proxy for biomass, nor for the rate of growth in terms of carbon (termed ‘primary production’). Five years before Kruskopf and Flynn (2005) had already shown as much, and quite clearly, in their paper entitled “Chlorophyll content and fluorescence responses cannot be used to gauge reliably phytoplankton biomass, nutrient status or growth rate”. Systematic changes in the chlorophyll content and productivity of phytoplankton are so well known that at least a dozen or so models have been developed of that adaptive response, termed ‘photoacclimation’, at least since Geider et al. (1998).

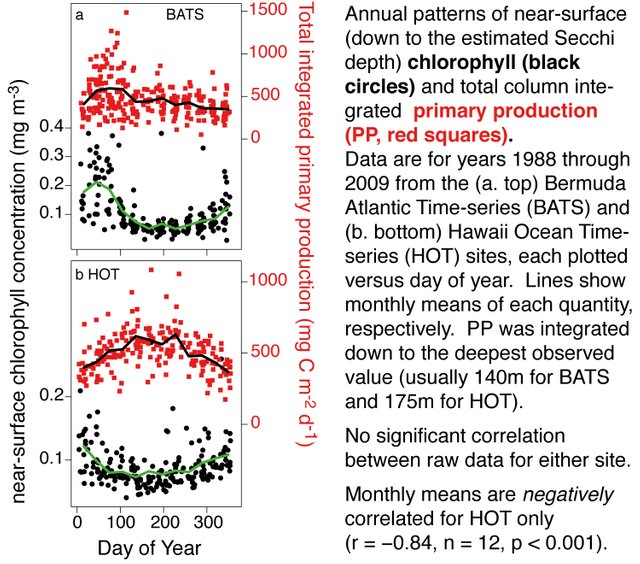

So I wrote and submitted a comment rebutting Boyce et al. (2010). Here’s the figure I made, using data from two sites where long time-series of observations are available.

The editors at Nature declined to publish my rebuttal. They mentioned in their reply that they had already published three comments. But those took issue with very different aspects of the paper.

Daniel Boyce was young and perhaps didn’t know about all the evidence for photoacclimation from years earlier. However, his co-authors include more senior researchers, who should know. Finally, one would expect the editors of Nature to select at least one knowledgeable reviewer.

I know from discussions with colleagues that many of us who study plankton were rather disturbed that Nature would publish such unfounded results. Nevertheless, Boyce et al. got a good deal of press. I saw blog posts about how global warming was killing the oceans. I’m sure it was good for Daniel’s career, at least in the short term.

The truth comes out, eventually

I am pleased that although it took fives years, the Nature group last year published Behrenfeld et al. (Nature Climate Change, 2015](http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v6/n3/full/nclimate2838.html). That paper makes clear the importance of the dynamic chlorophyll content of phytoplankton in the ocean.

In any case, don’t get too excited next time you see a single study portending doom, particularly when its conclusions are at odds with those of many other published studies. It takes years for a consistent body of evidence to be produced and sorted into a thorough understanding of the complex interactions of physics, chemistry, biology and ecology.

What strategy will succeed?

Nature requires species to adapt, and individuals to acclimate, in order to successfully procreate and persist. I hope that enough scientists, editors, and readers will hold accountable the authors of scientific publications concerning ecology and global warming. If so, the authors will have to account for the adaptive capacity of life and produce reasonably correct results in order to succeed in their careers. Otherwise, ignorance and even unscrupulousness may succeed all too well.

For more about short-term, long-term, and inter-temporal strategies, see my other post.

S. Lan Smith

Kamakura, Japan

September 6, 2016