The Top 10 List of Ancient Herptiles

Before (and during/after) the rise of dinosaurs, the Earth was ruled by gigantic reptiles and amphibians. These monsters were among the first to colonize the land, and were the dominant species on the planet for millions of years (and some have barely changed since due to their evolutionary success). I've compiled a short top ten list of what I consider to be the 'best of the best'; species that were the biggest and strongest, or had incredible adaptations that made them true biological marvels. (These 'rankings' aren't in any particular order...yet.)

Titanoboa: Titanoboa is actually a very new paleontological discovery, but has already taken the world by storm. After it was first discovered in 2009 in the coal mines of La Guajira, Colombia, the prehistoric super-snake went viral, quickly becoming almost as infamous as the mighty Tyrannosaurus Rex. Attaining lengths up to 45 feet long and weighing 2,500 lbs, the Titanoboa was deemed the largest (known) snake to have ever existed; for many, it was a nightmare made real. It lived during the Paleocene epoch (this is the period directly following the dinosaur mass extinction) in dense jungles, and is believed to have been very similar to today's green anaconda. The anaconda is the heaviest living snake on earth, and is renowned for its powerful constriction, literally crushing prey to death. Based on the musculature of the Titanoboa, paleontologists believe that the massive snake likely did not constrict its prey, but instead clamped down on it with powerful jaws like a crocodile.

On 22 March 2012, a full-scale-model replica of a 14.6 m (48 ft), 1,135 kg (2,500 lb) Titanoboa was displayed in Grand Central Terminal in New York City. It was a promotion for a TV show on the Smithsonian Channel called Titanoboa: Monster Snake which aired on 1 April 2012. Source (The program was great; I highly recommend it)

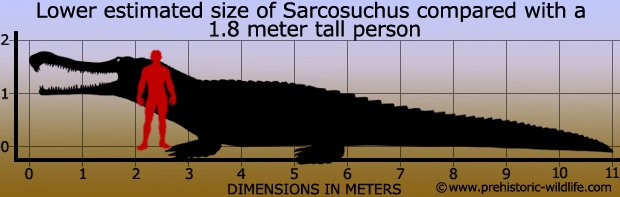

Sarcosuchus: There is no question why this reptile is known as the 'super-croc'. Over 40 feet long, weighing in at 8 tons, Sarcosuchus imperator was a powerful apex predator of the Cretaceous Period. It's jaws alone were five feet long (almost as big as a person!) and filled with 132 teeth to rip and shred prey...including dinosaurs that strayed too close to the water's edge. Despite its appearance and form being similar to that of a modern crocodile, Sarcosuchus was actually a member of the ancient crocodyliforms, an ancestor of today's true crocodilians. There are still aspects of the giant's life we don't fully understand; for instance, today's crocs tear meat off of their prey by “death-rolling”, however the biomechanics of the Sarcosuchus' skull indicate that it would not have been capable of such a maneuver. While we know that the monster hunted large animals, we still aren't 100% sure how it did so. Source

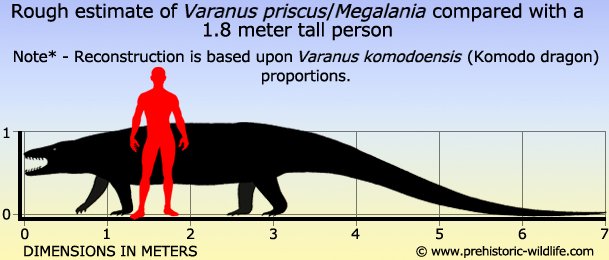

Megalania: The largest living lizard today is the komodo dragon, a huge island dwelling monitor that can attain lengths of up to 10 feet. But even this giant pales in comparison to its ancient ancestor Megalania, the largest terrestrial lizard that ever existed; over 25 feet long, this monitor was a voracious eater, feeding on mammals (such as kangaroos, elephants and tortoises), birds, reptiles and eggs (as its descendants do today). It lived during the Pleistocene era, and with fossils dated as early as 50,000 years ago, it's likely that the first aboriginal settles to Australia would have encountered them (imagine trying to fend one off!). Today, the komodo dragon is recognized as being a venomous species; belonging to the same clade, many paleobiologists believe that megalanias may have been venomous as well (this would make them the largest known venomous vertebrates. Source

While the species is officially extinct, rare reports still come from Australia and New Guinea that the megalania still exists. These reports have been dismissed as there is no evidence to support such claims, and the reports only began after the discovery of megalania became publicly known.

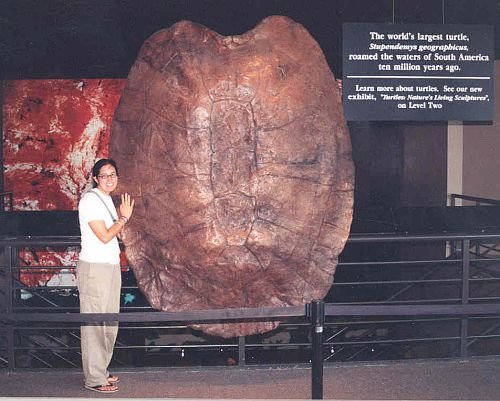

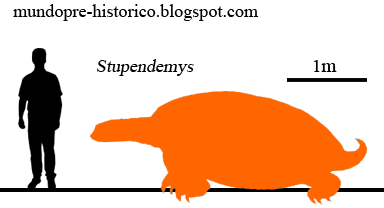

Stupendemys: Living in the murky swamps of the Miocene ear, Stupendemys is now confirmed to be the largest (known) turtle to have ever existed. The giant was a species of side-neck turtle; while many turtles pull their heads inside their shell to protect them, side-neck turtles do as their name suggests, tucking their head and neck to the side to protect themselves. Unlike the leathery-shelled Archelon (the species that previously held the record), the 11 foot shell of Stupendemys was comprised of bone and keratin like today's turtles, weighing it down immensely. Because of the incredible weight, scientists believe the turtle was actually a relatively weak swimmer, and lumbered slowly across the mucky bottom of the swamp. At such an imposing size, it seems like such a well armored beast wouldn't have to worry about predators, but tooth marks scarring ancient shells have revealed that something certainly tried to dine on the massive reptile. This begs the question: what giant super-predator might have driven Stupendemys to grow to such a massive size? Source

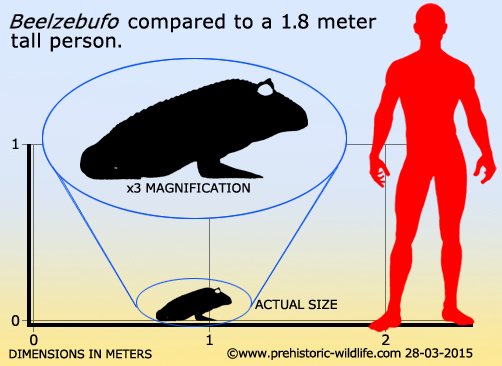

Beelzebufo: Named after Beelzebub (contemporary name for the devil), Beelzebufo was the largest frog to have ever existed. They resembled the modern day horned toads, and had an expansive mouth that could engulf prey that was large compared to their body size. Though they only grew to about 16 inches, Beelzebufo had an enormous appetite, with evidence suggesting that they very likely fed on hatchling dinosaurs! Recent fossil evidence shows us that Beelzebufo was suited with armor, and had bony scutes on its head and back for defense, protecting them from larger animals.

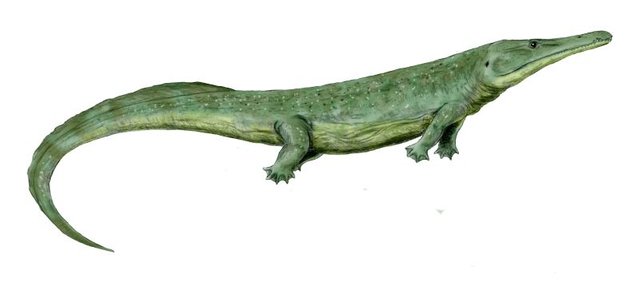

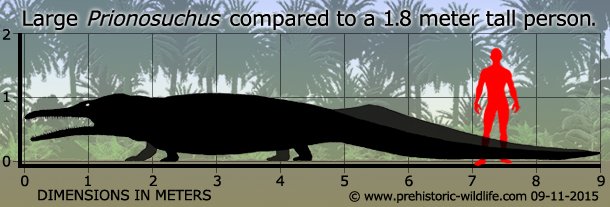

Prionosuchus: In 1948, L.I. Price introduced a large creature that resembled a crocodile...but this was no reptile. Named Prionosuchus, this huge amphibian belonged to a group of animals known as themnospondyls, salamander-like creatures that bore teeth (they also often had claws, scales and bony plates unlike modern amphibians). Prionosuchus was a behemoth compared to today's salamanders, attaining lengths up to 30 feet, making it the largest amphibian to have ever existed (our largest living salamander species, the Chinese Giant Salamander, only reaches about 6 feet max). With a tapered mouth that is very reminiscent of a modern gharial, Prionosuchus is believed to have hunted in a similar manner, an ambush predator that fed on fish and other aquatic species. Source

We've met some of the biggest and baddest, but size isn't everything! Reptiles and amphibians have had an incredibly diverse evolutionary history with species exhibiting amazing adaptations!

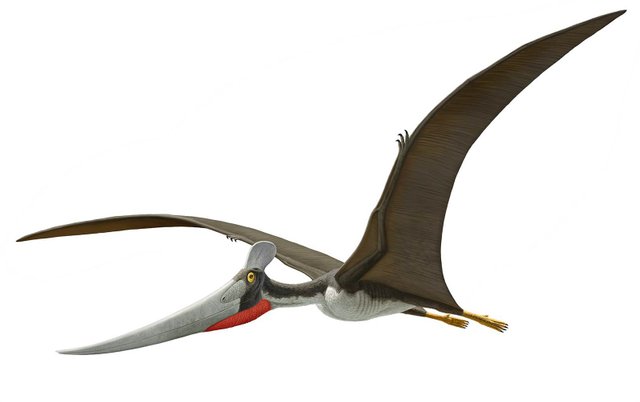

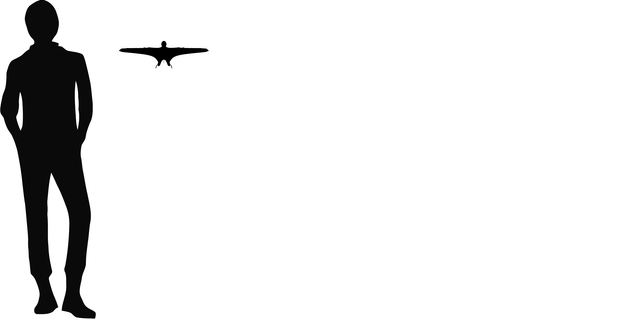

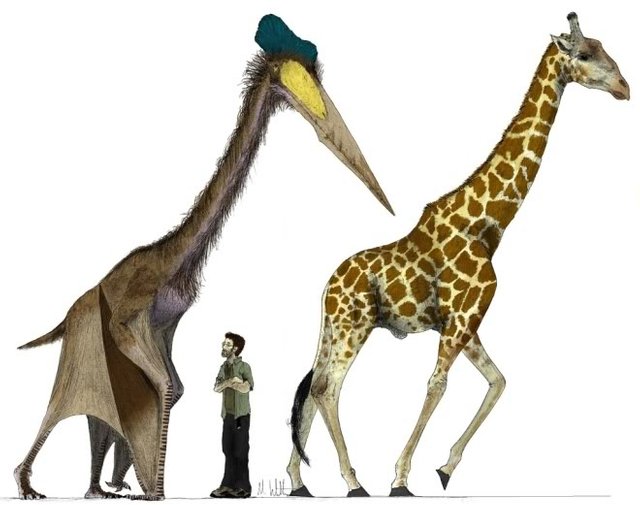

Pterosaurs: Flight is one of the most incredible adaptations of any animal, and reptiles were the first vertebrates to achieve true flight. Though often referred to as flying dinosaurs in pop culture, pterosaurs were actually ancient reptiles (though they are more closely related to today's birds that any existing reptiles). Their wings were actually comprised of their hands and arms: the 4th finger of the hand was incredibly long, and was connected to the body with a fleshy membrane that ran down to the ankles creating almost bat-like wings. Once airborne, pterosaurs could reach speeds up to 75 miles per hour and travel thousands of miles (truly flying instead of gliding or controlled falls). There is incredible variation among the many pterosaur species such as differing teeth, beaks, body coverings, and crests, and they differed greatly in size from the tiny anurognathids to the massive Quetzalcoatlus. Source

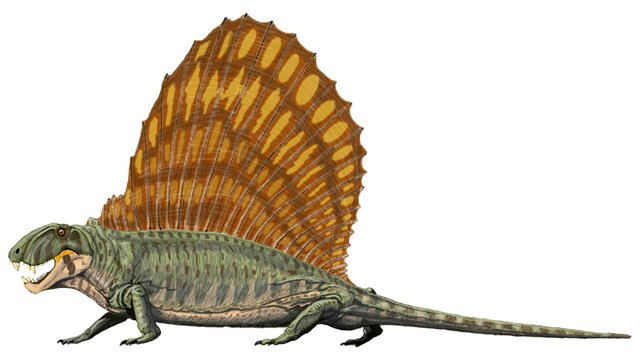

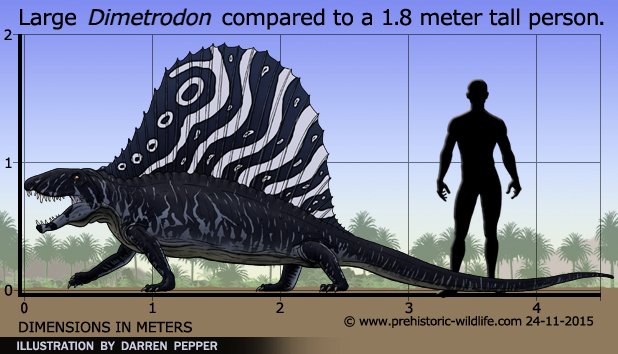

Dimetrodon: Dimetrodon is a fairly recognizable animal with its neural spine sail (formed from elongated spines extending off the vertebrae). The sail is thought to be an adaptation for thermoregulation; acting almost like a biological solar panel. Paleontologists have proposed that the increased surface area would have helped catch the sun's rays, more efficiently warming the animal. However, the sail is not the adaptation that makes dimetrodon special, and not why I chose to include it in this list. Dimetrodon was an early non-mammalian synapsid or "mammal-like reptile", one of the transition species between reptiles and true mammals (it's actually more closely related to us than to the lizards it branched off from!). While it closely resembled the reptiles it left behind, dimetrodon bore traits that would give rise to the mammals; dimetrodon was homeothermic, able to maintain a constant (if low) body temperature. This homeothermy would eventually give rise to our endothermy (or warm-bloodedness). In a way, dimetrodon is our evolutionary cousin on the family tree! Source

Acanthostega: You probably don't recognize this guy, but he's one of the most important species on this list (maybe #1 if I actually ranked them!). Acanthostega was a "stem-tetrapod", one of the first vertebrate animals with recognizable limbs. Though it is not a true amphibian, it was the intermediate species (alongside icthyostega) between lobe-finned fish and those capable of coming onto dry land. Though it is unlikely that Acanthostega ever ventured onto land itself, it did use its primitive limbs to navigate through shallow waters and aquatic plants. This movement allowed for greater weight-bearing of the pelvic girdle, which would one day allow for the transition to land. This amphibian relative also had lungs, but its ribs were too short to support the chest cavity outside of the water, so it had to rely on internal gills, much like some of today's salamanders. Acanthostega helped drive the evolution of limbs and their mobility, and is arguably one of the species that made the initial movement to land possible in the first place! Source

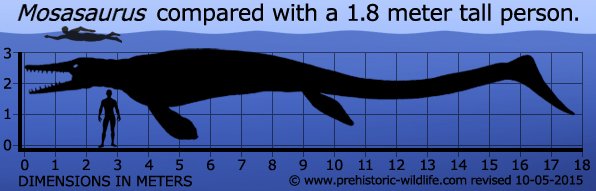

Mosasaurus: I couldn't do a top 10 list without including my personal favorite, Mosasaurus. Mosasaurs were giant aquatic lizards that were similar in shape to today's monitors (some herpetologist believe they may actually be the ancestor of modern varanids), however they were perfectly adapted for an aquatic lifestyle. The largest known species, Mosasaurus hoffmannii may have exceeded 55 feet in length, and was an apex predator of the inland seas during the Cretaceous period. Like sea turtles, the Mosasaur breathed air, and had to surface regularly for a breath; unlike turtles, which must make their way onto land to lay eggs, the Mosasaurus gave birth to live young without having to leave the water. Like snakes, they had double hinged jaws and flexible skulls to gulp down large prey; inside the body cavities of Mosasaurs paleontologists have found the remains of seabirds, bony fish, ammonites, sharks, marine reptiles and even other, smaller Mosasaurs. Source

Photo Credit: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Note: (Because someone might flag me) I want to point out that this post is a continuation of a post I previously wrote for the facility where I work. I included a lot of the same language into this post, but I am the author of both. The original post can be viewed here: http://thevlm.org/jurassic-world-herpetology-edition/

Yikes, we were just snacks!

Cryptozoology is very interesting. It would be so awesome if all those animals are still here. Swimming in mosasaurus infested waters would be only for the crazies :)

I'm actually planning on doing a post in the next couple days about the science behind cryptozoology. I think the field is very different from what most people believe it to be!