Saving Endangered Species: Is It Worth It?

A couple days ago, I wrote a post regarding the protection of endangered species, and how we should go about saving these animals by safeguarding critical information. All the comments I received were great; several steemians had different ideas about how we could possibly publicize important information while still protecting animals (thanks to everyone who commented!). However, there was one comment that really made me think, and I probably spent more time considering my answer to this user than any of the others who commented. Here is (part of) the comment that was posted by @ats-david in response to a hypothetical scenario I had included in the post (I recommend reading the article for full context).

The question here seems to make the assumption that these newly-discovered and already endangered species need to be saved/protected. And it almost assumes that the fact that they're endangered is somehow the fault of humans or that it is our responsibility to save/protect them. I don't think that searching the world for rare species and then trying to save them from extinction is productive for science/scientists.

Depending on where you stand on supporting conservation initiatives, this might seem callously uncaring or like sage wisdom, but the fact is @ats-david is making some very valid points. Obviously, he isn't in favor of animals going extinct, but he recognizes the costs associated with trying to save these species, and the question becomes "is it worth the challenge?" Protecting species on the brink of extinction is an endeavor that costs incalculable time, energy, resources and funds...and there is by no means any guarantee it will be successful. There is also the question of morality as well; is it our place to try and save these species? Or would it be more natural to let nature take its course? Today, I want to try to break down the argument and explain why endangered species conservation is profoundly important, even when it comes with a hefty price tag, both morally and literally.

When we list a species as endangered, people often to try to assign or deny blame for the decline of these species. Sometimes it's easy to see where the responsibility lies; whales for instance were hunted for centuries almost to the point of extinction for the production of oil. Countless species have been overhunted for food, hide, animal products, medicinal properties, or even just because they were a nuisance or in the way. Others decline as a direct result of human encroachment, habitat loss and pollution. In these instances, it's fairly easy to admit our responsibility for the decline of these species. But it gets harder when other causes are factored in, such as climate change. A large number of species are at risk due to the shifts in Earth's climate; many people argue this is our fault as we are having a profound impact on the shifting climate, while others deny the blame claiming that it is part of a natural sequence of events (or outright denying the shifts entirely). However, playing the blame game is a foolish waste of time; generally there are several causes behind the decline of a species, some caused by humans and others of a more natural origin. In all likelihood, most endangered species are at risk as a result of both, so simply stating we either are or are not completely to blame isn't entirely accurate. But whether or not we play a role in their decline, is it our responsibility to save them?

So what are the arguments against conservation initiatives; for what reasons would it be better to simply let these species pass on their own? First is the obvious monetary cost; a 2012 study estimated that it would cost around 76 billion dollars every YEAR just to protect endangered land species. Trying to protect all the endangered marine species could cost far more. That is a TON of money that could go to new infrastructure, feeding the hungry, fighting diseases, any number of other important causes. And at the end of the day there is no guarantee we can save these species; there are animals we began protecting half a century ago that remain critically endangered or have been lost. That's a lot of money just down the drain. The next problem is that there are many animals people don't WANT to save. Wolves for instance were hunted almost to extinction because ranchers wanted to protect their livestock; today, people are fighting against wolf conservation because they fear the return of this apex predator. It's easy to say "we have to save the tigers!", but how do you convince the people of South East Asia (where tigers attacks have killed 373,000 people over the past 200 years [Source]) to protect them? Sometimes we simply don't want to save a species because their extinction is seemingly beneficial to humans.

A beautiful animal, but do you want one in your backyard?

People are hesitant save individual species because they believe it to be unimportant in the grand scheme of life. Yes, we all love cuddly pandas, and their loss would be tremendously sad, but how would the disappearance of this one animal affect us? And how would it affect the environment? Simply viewing the organism as a single species leads to people believing that animal is not overall important, and not worth the effort or money to save. Lastly, people try to explain away extinction as a natural series of events, and we have no place intervening in nature's design. At it's core this isn't an unreasonable argument; old species often have to go extinct for new species to arise. So if it is perfectly natural for species to die out, why are we fighting so hard to prevent that? Why spend billions of dollars saving animals that are not going to survive anyway? With all these reasons against conservation initiatives, it is easy to understand the reluctance of many people and nations to take part in the costly endeavor. But now it's time to look at the overwhelming reasons why we must protect these species.

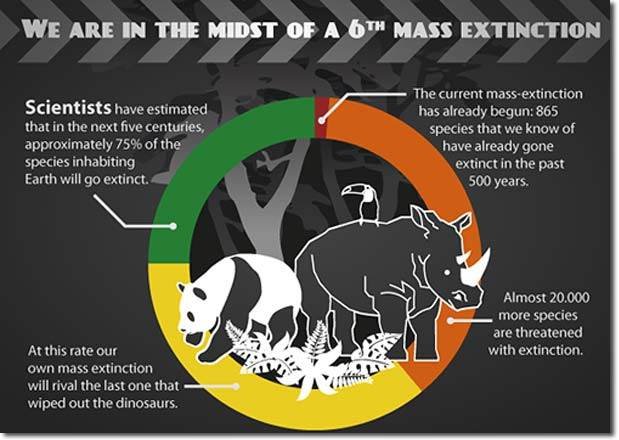

So let's start addressing the merits of conservation by looking at the rates of extinction. Extinction is indeed a natural and beneficial part of life; the world would not be the beautiful place it is today without it. Old species that are ill-adapted for survival die out, and new species arise to fill the place they left (a process called speciation). Species have always gone extinct and species will always continue to go extinct, and there isn't much we can do to change that fact. However, species are now going extinct at a much faster rate than they did only a couple hundred years ago; a recent study estimated that the rate of extinction has increased 100 fold over the last hundred years. We are now in the midst of what is called the Holocene extinction (the 6th mass extinction event on planet Earth); unlike previous mass extinctions caused by disasters such as asteroid strikes, volcanic eruptions and natural climate shifts, this extinction crisis is almost entirely caused by humans, directly or indirectly (Source). Species are now disappearing faster than new species arise to replace them. Now the argument begins to falter; we can't simply dismiss conservation because extinction is a natural event when what we are seeing is unnatural.

We can't simply determine the worth of a single species by how it affects humans; we have to take a step back and look at that species' role in the ecosystem as a whole. Every species, even the smallest, most minute creatures, are a link in the web of life, and removing any link has its consequences. The loss of a single species can have an incredibly negative impact on other local species, and it may drive those other organisms towards the brink. I can use my own state, Virginia, as an example. When settlers first arrived in Virginia, the land was home to a variety of apex predators, the big three being wolves, black bears and mountain lions. Over time, these species were over hunted for their furs and to clear land for human use. They were shot on sight as they represented a threat to humans and our livestock. Today, there are no wolves in Virginia, and mountain lions have decline drastically (bears are hanging in there, but even their numbers are a far cry from what they once were). Without these natural predators, prey species, in this case deer, began multiplying beyond their carrying capacity because there was nothing to keep them in check. Today, deer are a huge problem in Virginia, and they take a toll on the local economy through crop destruction and property damage, in addition to presenting a risk to motorists. But the deer are suffering as well; because predators naturally weed out weaker or sicker prey, diseases are spreading through deer populations, most notably chronic wasting disease. States are now attempting the reintroduction of predators to naturally control these species, and prevent the spread of diseases, but the damage may already be done. Though the elimination of a single species, like the wolves, may seem insignificant, the consequences of removing them have created ripples that now impact humans.

Some species are keystone species, meaning that they literally carry the life of the ecosystem on their back. Without these animals, the entire system cannot survive or at least is drastically changed. The beaver, though not endangered, is a perfect example; by damming up rivers and redirecting the flow of water, a single family of beavers can change an entire landscape. Hundreds of plants and animals rely on these beaver-built ecosystems to survive. If the beavers were removed from those ecosystems, the entire environment would suffer as a result. This is already happening with endangered species as well; the gopher tortoise (check out my past post on these guys) is a reptile that is vastly important to the southeastern United States. Gopher tortoises are named because the spend all of their time digging deep burrows (up to 9 feet deep and 50 feet long. These burrows provide shelter for many different species, but more importantly, they are a safe haven for animals during forest fires. Over 400 species have been observed hiding in the tortoise burrows during these deadly blazes! But the gopher tortoise is in decline; as few tortoises remain to build these critical life saving burrows, more species will face the pressure of these forest fires.

Other species are important bio-indicators. Frogs and other amphibians are our "canaries in the coal mine"; because they are such sensitive animals, they are generally the first organisms in an ecosystem to show signs of declining health. When we find an amphibian species that is endangered, this turns on the warning lights in the minds of ecologists. If the amphibians are suffering and in decline, the ecosystem is most likely suffering as well, even though we may not see it yet. This basically gives a chance to diagnose the patient before the onset of severe symptoms, thereby giving us a chance at full recovery. By addressing the factors pushing the amphibians ever closer to extinction, we have hope of restoring the health of the ecosystem as a whole. Of all the species of amphibians on earth, 1/3 of them are in decline or endangered; this is our early warning that much of the global ecosystem is slowly heading toward environmental collapse.

You might see just a pretty frog, but I see a critical health barometer.

Now @ats-david makes a good point: trying to save individual species from extinction is not a productive use of time or resources. Fortunately, that is not what we are doing. When we work to save a species, we are not just working with that single organism; we have to address its roll in the entire ecosystem and the health of that ecosystem. When we undertake conservation initiatives, we spend a lot of time planning our how we are going to protect the entire habit. You can't save an elephant if there isn't a safe, healthy place for them to live or plenty of natural foods for them to eat; you need to make sure that you are protecting that system as a whole. This is where conservation becomes critical; by focusing in on these critically endangered animals on the brink of extinction, you are actually benefiting all the species they interact with. To make the habitat more hospitable for an endangered frog, you increase the overall health of the ecosystem. Even if the initiative fails, and the animal DOES go extinct, the conservation project has likely helped the entire habitat at least partially recover, even if the target species didn't stand much of a chance. Whether you have reduced poaching, decreased human pressures, controlled/eliminated an invasive species, or even just educated the local population, the ecosystem begins to have a chance at recovery. We claim that it is about the species (because humans identify with cute animals), but it's really all about the environment.

Despite the huge cost of conservation, it actually can be incredibly beneficial to the local, national and international economy. As I mentioned before, the explosion of the deer population in Virginia has had pretty devastating effects on local economies and livelihoods, however, reintroducing and working to replenish native predator populations has proven to be a cheap and effective means of bringing these animals back in check. Responsible hunting is an important form of conservation; many northern states offer highly-regulated moose hunts to keep the herds strong and healthy, while also bolstering local economies and tourism. Restoring ecosystems can have a profoundly positive impact on tourism; with more people traveling to explore the natural world and breathtaking resources (for example the rain forests of South America, African Serengeti, or Great Barrier Reef), countries have the opportunity to make good money off tourism. Though it may present a greater up-front charge, the protection of our natural resources benefits us in the long run.

There are a lot more reasons out there in defense of conservation initiatives. At the end of the day, it really boils down to a single question: do we want to conserve our natural resources? I believe for most people the answer is overwhelmingly yes, however there is enough disinformation or misunderstandings out there that make putting these practices into action very daunting. Conservation is not an easy practice and it never will be, but nothing worth doing ever is. I believe the global fight to save our planet might be what finally unifies us; together we have the ability to responsibly reshape an entire planet, benefiting our lives, and all life on Earth.

Image Links: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Video Link: 1

Wow great tie in with morality and the blame everyone else. I have always found conservation more appealing however sometimes species just don't evolve or keep up to changing conditions no matter what. Take the passenger pigeon for example 3 billion to zero in less than a lifetime. Easy to blame people for it but there are plenty of other pigeon species that continue to thrive why didn't they?

Thanks! Yeah it's so hard to assign any kind of blame; there's probably dozens of reasons they went extinct. Maybe it was just their time to go and we only contributed a little bit to their extinction.

Exactly then again look in any major US city pigeons are everywhere so they should be too. Something out of our control I think.

We need to show more respect to our Mother Nature. Green parties, UN, WWF, Greenpeace...they all need our support. 2023 will be a bad year for the climate according to studies. So sad :(

The best article @herpetologyguy. Thanks for sharing