Electricity: From Turbine To Home - The Physics

Electricity separates man from ape. The fruits of mankind's greatest intellectual labours have granted us the ability, unique to the animal kingdom, to harness energy. Humanity wields energy like a weapon and covets it like gold.

So meteoric has been its rise that the U.N. hopes that all 8 billion Earthlings will have access to electricity by 2030.

But how does civilisation's lifeblood make it to our homes?

Electromagnetism

Exploration of electricity must follow a discussion of magnets and electromagnetism.

Magnets

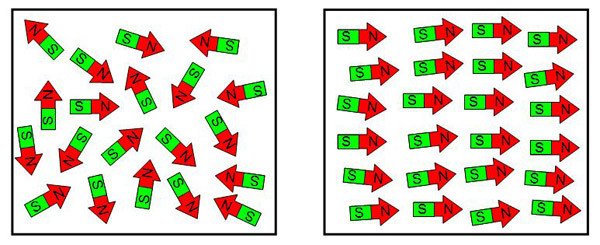

The electrons present in a material act as microscopic magnets of a certain polarity, since spinning charge produces a magnetic field. When regions of many adjacent electrons have aligned polarity, they may be lumped together as one magnetic domain. In most materials, the polarity of adjacent domains is random - there is no discernible pattern nor overall magnetic dipole. In magnetised materials, however, these magnetic domains align.

Domains within a magnetised material (right) align.

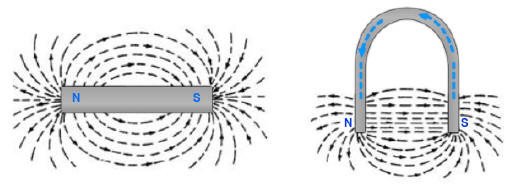

By shaping such a material, a magnetic field pointing in the direction of the domains can be produced in the space between its two ends (poles). This is the basis of magnets, and crucial to electromagnetic induction in generators.

By convention, magnetic field lines from a magnetised material are considered to point, along the curved path of least resistance, south-to-north within the material and north-to-south in the surrounding air.

Induction of Current

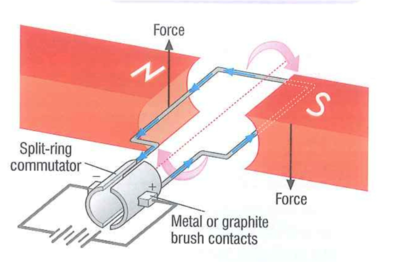

A charged particle moving perpendicular to a magnetic field is deflected at right angles. In the same way, a copper wire (carrier of free electrons) moving through a magnetic field undergoes a deflecting force which 'pushes' electrons within. As long as the electron-carrier moves at a constant velocity - in generators, the carrier usually rotates with constant angular velocity within a field - its electrons are propelled around the circuit at a constant rate (i.e. a current is induced).

In effect, a permanent terminal at each end of the system (one positive and the other negative) has been set-up and separated by a potential difference to drive the flow of charge - this is similar to a conventional battery, which uses chemical potentials to (for a limited period) establish opposing terminals.

In power stations, the motive force for electromagnetic induction is provided by a turbine, which transfers various energy forms into the kinetic energy required to rotate the charge-carrier within the field (60% of UK turbines are still powered by the burning of fossil fuels to produce steam; the use of alternative energy forms such as solar and nuclear are somewhat cleaner means to the same end: steam production).

Each half turn, the terminals 'swap' as the deflecting force pushes electrons in the opposing direction. Current produced by generators on the National Grid, for example, reverses 50 times each second and is termed alternating current.

Tricky to Transport

One of the many problems Edison 'employed' Tesla to solve was the loss of energy as heat from currents in wires of significant length. To Edison's dismay, the solution that Tesla provided was viable only for alternating current, while Edison's empire at the time ran on direct current produced by local generators. Fortunately, Tesla later teamed up with businessmen to finance alternating current and we still use his remedy - the transformer - today.

When current flows in a material, some energy is lost as heat thanks to the material's intrinsic electrical resistance. The greater the current, and the longer the distance over which it travels from power station to home, the more energy is dissipated by resistance.

With increasing distance, the transport of electricity quickly becomes environmentally and economically unfeasible.

However, by 'stepping up' and 'stepping down' the current before and after transmission, energy losses can be mitigated.

A transformer consists of an iron core ring wrapped in two separated, insulated coils. The primary coil is connected to the alternating current input circuit, while the secondary coil is connected to the output circuit with a load resistance.

The input current produces an oscillating magnetic field within the core. This changing field has the same effect on the secondary coil as rapidly moving the coil within the field: an alternating current is produced in the output circuit and a potential difference set-up across the load.

A step-up transformer has fewer turns on its primary coil than its secondary coil. This has the effect of increasing the potential difference and decreasing the current in the output circuit; stepping up the voltage to around 400,000 V greatly reduces energy losses and facilitates the viable transport of electricity nationwide.

However, electricity cannot be supplied to the mains of households at 400,000 V - such a large potential difference would likely allow the current to bridge air gaps, delivering home-made lightning bolts.

Instead, step down transformers reduce the voltage to a level suitable for underground and near-overhead local transmission (11,000 - 33,000 V). Step down transformers within the home decrease this voltage further (to 230 V) for safe household use.

Transformers are used by the National Grid system to balance safety and efficiency.

Unfortunately, no transformer can step down your stupidity...

If you enjoyed this article and would like more, follow the everyday science blog for your daily dose of science.

References:

www.nationalgrid.com

www.roymech.co.uk

www.thisisphysics.wikispaces.com

www.sciencebuddies.org

Step-up and Step-down Transformer - Educational Videos and Lectures

Wow very useful and informative thanks for sharing

Congratulations @cjrc97! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP