Believing What We Remember? Many of our beliefs are tied to our personal memories, but memories are fallible

[The following is an edited excerpt from my new book, Belief: What It Means to Believe and Why Our Convictions Are So Compelling (Prometheus books, April 2018)]

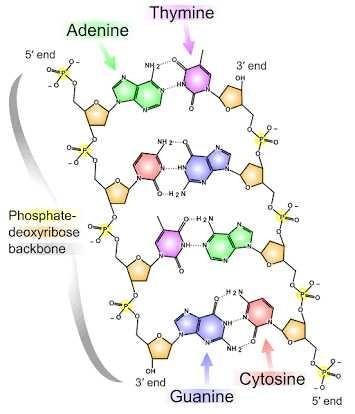

source wikimedia commons

- Whatever you believe about the world and about yourself at this moment—without consulting books or the internet—comes from your memory. In a real sense, even your belief about who you are—your self-identity— is based on who you remember yourself to be. It is your memory that provides you with a sense of continuity in your life.

All About Identity

- We contain multitudes," wrote Walt Whitman, referring not to the highly contested diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder but to the fact that we see ourselves radically differently in different contexts. Everyone struggles with that existential plum, "Who am I?" For people who are overly concerned with other people's impressions, or who feel a core aspect of themselves, such as gender or sexuality, is not being expressed, this struggle is acute.

Until not so many years ago, experimental psychologists viewed memory simply as a very sophisticated recording process, and any errors were treated as defects in the process. A mountain of research now clearly contradicts that view. We now know that errors of memory are commonplace, not rare, and rather than being caused by defects, they reflect the fundamental character of the memory process. Memory is not some sort of cerebral video recorder that captures events around us as we experience them.

Memory

- Memory makes us. If we couldn't recall the who, what, where, and when of our everyday lives, we wouldn't be able to function. We mull over ideas in the present with our short-term (or working) memory, while we store past events and learned meanings in our long-term (episodic or semantic) memory. What's more, memory is malleable–and it tends to decay with age. So stay sharp by learning about the science of recollection.

There are a number of influences that can distort or corrupt our memories and the beliefs associated with them:

Retroactive falsification: When an event is recalled a number of times in succession, the details tend to become more consistent with one’s belief about the event. For example, suppose you describe a recent experience with a rude waiter. You recall that your partner had complained about the soup not being hot enough, and that you sarcastically suggested to the waiter that the chef should learn how to cook. The waiter then snarkily advised you to dine somewhere else next time. As you relate this account, your listener responds by suggesting that your sarcasm may have provoked the rude response, thereby challenging the “rude waiter” theme of your story. Now, the next time you tell the story, you may unwittingly or perhaps even deliberately reduce the likelihood of such a challenge by leaving out the bit about your sarcasm. Each new reconstruction influences the following one, and over several retellings, you may actually forget all about your sarcasm. This is retroactive falsification, and it can occur completely without awareness. It serves to maintain your belief, in this case that the waiter was spontaneously rude.

Misinformation effect: The misinformation effect occurs when misleading information acquired subsequent to an experience leads to alterations in memory and belief about the experience. For example, in one study participants were presented with a series of photographs portraying a thief stealing a woman’s wallet and then putting it in his jacket pocket. Subsequently, the participants listened to a recording that described the series of photos, but the recording indicated that the thief had put the wallet into his pants pocket. A substantial proportion of the participants later recalled that the photographs had shown the thief putting the wallet into his pants pocket. The subsequent misinformation had become part of their memories, and their beliefs about what had occurred.

Imagination inflation: Research has demonstrated that something imagined in the context of a particular memory is sometimes later “remembered” as having actually happened. As result of this imagination inflation, the “memory” may carry with it all the corresponding emotional and physical reactions that would occur were the memory accurate.

I'm always "scared" of retrospective falsification because it is a form of bias and I always try to be as objective as I can. So when I recall a story such as your rude waiter example, I try to admit -firstly to myself- my own mistakes and how I might have contributed to the outcome of the story. This exercise has personally helped me have a more accurate memory in events involving other people because I try not to let emotions distort memories, whether they are good or bad memories.