Joseph Juste Scaliger

How are the mighty fallen!

It is hard to imagine a fitter subject to which these words might be applied than the French scholar Joseph Juste Scaliger, a man whose wit and erudition were once held in such high esteem that the Encyclopædia Britannica described him as the greatest scholar of modern times, but whose reputation among the truth community today could hardly be lower. The same man who, according to Mark Pattison, was perhaps the most extraordinary man who has ever devoted his life to letters and who possessed the most richly stored intellect which had ever spent itself in acquiring knowledge is now routinely convicted of having fabricated much of what passes today for history. He conjured up out of thin air, it is said, an entire millennium that never was and populated it with men, women and events that never were. Far from being scientific, it is alleged, Scaliger’s practices were occult, being based more on numerology than on mathematics, more on astrology than on astronomy (IEF-USFEU).

Those who convict Scaliger of these crimes do so without a trial. For how can one fairly try any man on such charges without being intimately acquainted with the writings in which he is alleged to have committed his crimes? And can the average reader be acquainted with Scaliger’s books on history and chronology, which were written in Latin and have never been translated into English?

In this series of articles, it is my intention to give Joseph Scaliger the trial he deserves. I will not condemn him without hearing his side of the story. Did he lay secure foundations on which the modern edifices of history and chronology could be constructed, or did he overthrow true history and replace it with a counterfeited account of human civilization that is still taught in our schools today?

Joseph Juste Scaliger was born in Agen, a small town in the southwest of France, on 5 August 1540 (Julian Calendar = 15 August Gregorian). His father, Giulio Cesare della Scala, was an Italian scholar and physician, who had settled in Agen in 1525 when his patron Antonio della Rovere moved to the city to take up the Bishopric of the local Diocese.

Giulio claimed to be a scion of the noble family of Della Scala, which had ruled Verona for over one hundred years in the 13th and 14th centuries—a claim accepted and defended by his son. Modern scholarship, however, has failed to connect Julius with this family, either through his father Benedetto Bordone or through his mother Berenice Lodronia. Joseph claimed that his paternal grandfather was in fact Benedetto della Scala, son of Niccolò della Scala and grandson of Guglielmo della Scala (Scaliger 1594:Family Tree).

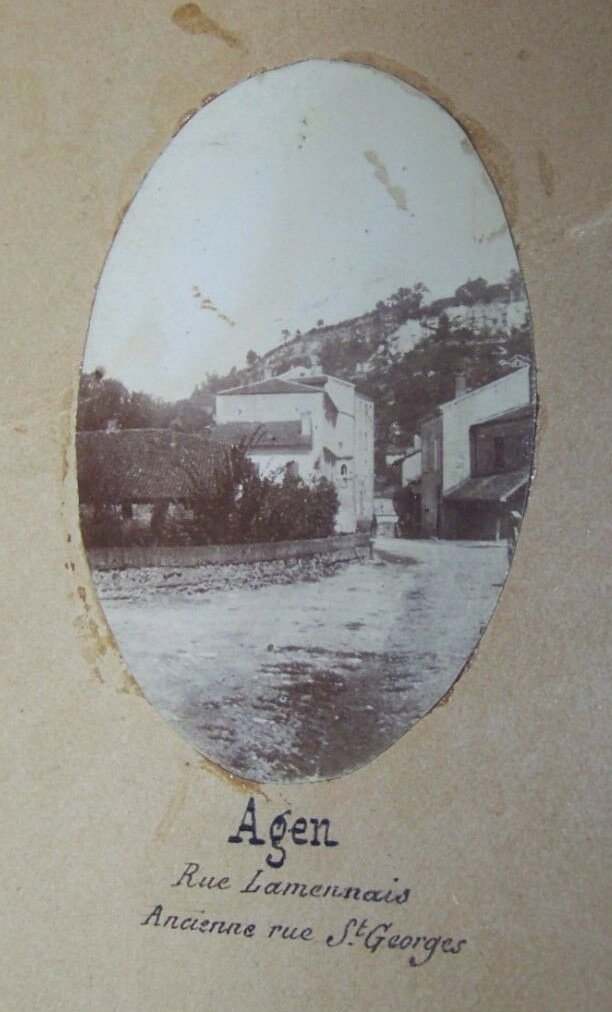

Joseph’s mother, Andiette de Roques Lobejac, had been a sixteen-year-old orphan in 1529, when the forty-five-year-old Giulio married her. She too was alleged to have aristocratic blood. Joseph was the tenth of fifteen children borne by Andiette—the third of her five sons. He was born at the Scaliger residence on the Rue Saint-Georges (= Rue de Cordeliers?), across the courtyard from the Ancienne Église Saint-Hilaire d’Agen:

The house lived in by [Julius Caesar Scaliger and Andiette de Roques Lobejac], as by their descendants as far down as the nineteenth century, was situated in Saint-Georges Street, opposite the façade (northeast) of the Church of the Cordeliers ... it occupied the emplacement of the [current] house of Sr Maupas, which forms the angle at the right of Saint-Georges Street and the Boulevard Scaliger. (Hall 159)

Rue Saint-Georges is now called Rue Lamennais, though there is still a plaque with the former name. It was named for Porte Saint-Georges, one of Agen’s former town gates—about 300 m to the north—which was destroyed during the French Revolution.

Agen lies approximately halfway between Bordeaux and Toulouse, on the River Garonne, in the Province of Guyenne. In the 1540s, it was a small town, distinguished from its neighbours by the Cathedral of St Caprais—episcopal seat of the local Diocese of Agen. Joseph’s early years in Agen were in no way out of the ordinary. He was baptized in St Hilary’s.

In 1552, when he was twelve, he and two of his brothers were sent to be educated at the College of Guienne, a Latin school in Bordeaux. Here they remained for three years, until an outbreak of the Plague in 1555 forced them to return to Agen. This brief spell of schooling was the only formal education Joseph received before attending college.

From 1555 until 1558, Joseph acted as his father’s amanuensis. These were Joseph Scaliger’s formative years. From his father he imbibed a love of Latin letters, both verse and prose, and a work ethic that was to serve him in later life. He also inherited his father’s love of poetry, and from an early age he was practised in the art of Latin versification. He even composed a Latin tragedy Oedipus at the age of sixteen—it has not survived. The education he received at his father’s hands was arguably better than the one he would have received at any college. By the time of his father’s death—21 October 1558—Scaliger was no longer a pupil, but a fledgling scholar in his own right.

After the death of his father, Joseph moved to Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne, primarily to study ancient Greek under the leading Classical scholar of the day Adrian Turnèbe. Those who do not know Greek, he once remarked, know nothing at all, and Julius had taught his son no Greek. After only two months, however, he realized that he was out of his depth, and he decided to teach himself instead. After just twenty-one days, he had worked his way through Homer with the help of a literal Latin translation, compiling his own Greek grammar and lexicon as he went along. After Homer, he moved on to the other Greek poets, orators and historians. When he had mastered ancient Greek, he proceeded to study Hebrew and Arabic with the same assiduousness.

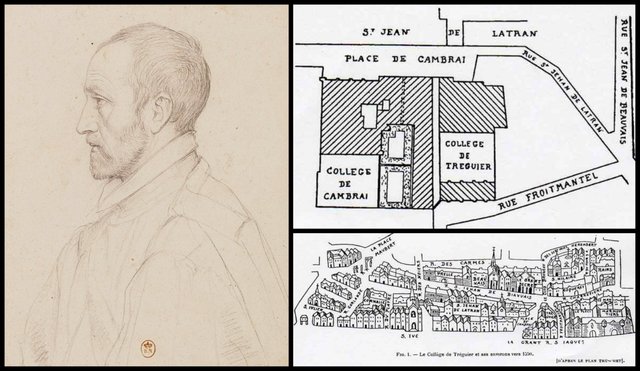

Among his teachers in Paris, perhaps the most influential was Jean Dorat, a member of the literary association La Pléiade and a teacher of Greek at the Collège Royal, which was then housed in the Collège de Tréguier, across the street from the Sorbonne. Scaliger continued to write Classical verse throughout this period. Most of his poems were translations from Greek into Latin or from Latin into Greek. He also composed some occasional poems of his own composition, including a few in French. This delight in versification—which Scaliger sometimes condemned as a personal foible—engrossed him to the end of his days (Pattison 212-218).

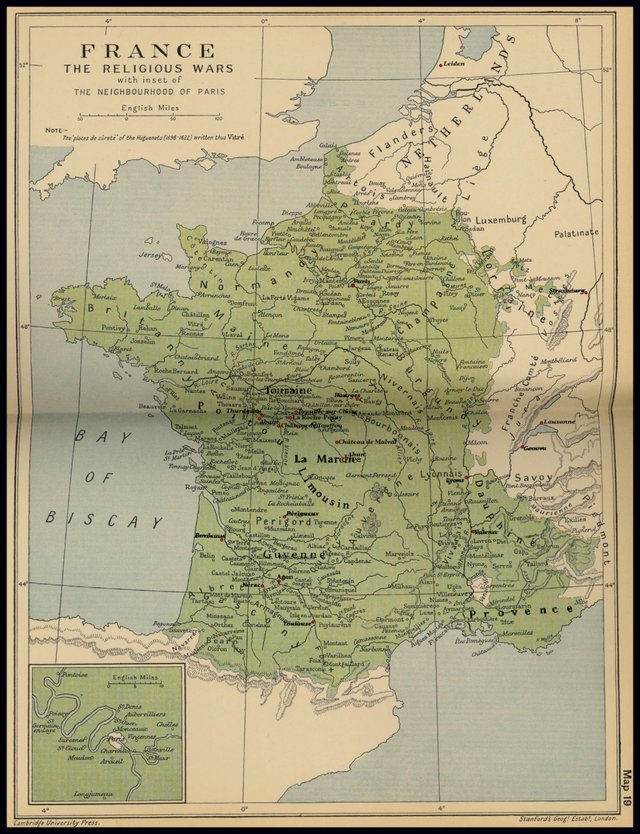

In 1562, Scaliger took a decisive step, which determined the whole course of his adult life: he converted to Calvinism, becoming a French Huguenot. Joseph’s father, while remaining a Catholic, “had exhibited in his last years an almost heretic aversion to the abuses of the [Catholic] Church” (Blake 86). In 1562, friction between the French Catholics and Huguenots broke out into open conflict. The ensuing Wars of Religion were to last until 1598. Joseph’s decision may have been influenced by the cruelties he witnessed in Paris during the First War of the Huguenots (1562-63). The decision to become a Protestant barred Scaliger from ever holding a post at the University, and forced him to seek the protection of a powerful lord.

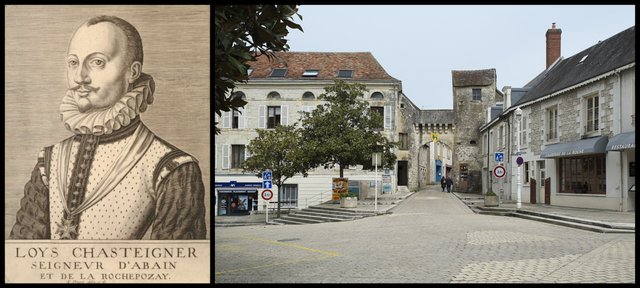

In 1563, Jean Dorat recommended Scaliger as a secretary and travelling companion to Louis Chasteigner, Lord of La Roche-Posay, a small provincial town situated on the left bank of the Creuse in Poitou. Louis had also studied in Paris under Turnèbe and Dorat. The two men became fast friends, and remained so until Louis’ death in 1595. Scaliger became, as it were, a member of Chasteigner’s family. The two men first embarked on a sort of Grand Tour, taking in Italy, England and Scotland between 1563 and 1567, during the so-called Armed Peace, brought about by the Edict of Amboise. The following three years were spent in France in active service. These were years of camp life, dictated by the exigencies of the Second and Third Wars of the Huguenots (1568-70). Chasteigner was Catholic, but La Roche-Posay was regarded by the French government as a disaffected Huguenot village. Scaliger, it seems, spent these years—1568-70—in Agen, fighting on the side of his fellow Protestants (Pattison 228):

Returning to France, he found it in the throes of the Second Religious War. Fighting in the ranks of the Huguenots, he took an active part in this war and in the Third that soon arose out of it; during this time he lost what he still owned of his parents’ estate. Bitterly, he railed against the citizens of his native Agen. Most of his friends fell in the murderous battles. (Bernays 39-40)

According to Blake, however, Scaliger spent these years more or less in the service of his patrons (Blake 86). As a Huguenot in the service of a Catholic nobleman, Scaliger found himself in a curious predicament during the Wars of Religion. It seems that he only took the field in the Huguenot cause in 1568-70 in defense of his property at Agen, while Chasteigner was prosecuting the war in another theatre. That he fought in the ranks of the Huguenots is made clear in one of his own letters (Heinsius 140, Wild 116). For the next twenty-five years of the conflict, Scaliger served Chasteigner faithfully, but he was never obliged to take up arms against his co-religionists in the field.

None of the biographical sources I have consulted clarifies Scaliger’s rôle in the Wars. Nor do any of them explain how a Huguenot could have served a man who was not only a Catholic but a military commander in the field. There is a mystery here that none of Scaliger’s biographers has yet solved.

In spite of his nomadic existence, Scaliger continued to work throughout this period. In 1565, his edition of Varro’s De Lingua Latina came out in Paris, and by 1568 he had completed his edition of the Appendix Vergiliana, though it was not published until 1572—by Guillaume Rouillé in Lyon. This work, which lacks the scholarship and polish characteristic of Scaliger’s later editions, includes the so-called Catalecta, an anthology of pieces from several different Roman poets. It is still acknowledged as the earliest anthology of Latin poetry. The full title of the work is Appendix P. Virgilii Maronis cum Supplemento Multorum antehac Nunquam Excusorum Poematum Veterum Poetarum [The Appendix of Publius Virgilius Maro, with a Supplement of Many Never Before Printed Poems by Ancient Poets].

When the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (8 August 1570) brought the Third War of the Huguenots to a conclusion, Scaliger took up the offer to study Roman Law at the University of Valence under the foremost jurist of the day, Jacques Cujas. There followed more than two years of peaceful study in the Dauphiné, on the banks of the Rhône. Cujas quickly came to hold Scaliger in high esteem, later describing him as the most learned Joseph Scaliger, with whom one disagrees at one’s peril (Grafton 1983:122).

During these years, Scaliger made full use of Cujas’ extensive library, which filled seven or eight rooms and included five hundred manuscripts. The childless Cujas actually bequeathed this library to Scaliger, but by the time he died in 1590, his second wife had borne him a daughter, Suzanne, who inherited all his books (Pattison 151-152).

This idyll was shattered by the momentous catastrophe of 1572, the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (23-24 August), when thousands of Huguenots were murdered by Catholic mobs in Paris. Many more died in subsequent massacres in the provinces. Scaliger was about to accompany the Bishop of Valence, Jean de Monluc, on an embassy to Poland when the first massacre took place:

Queen Catherine had deputed Monluc, Bishop of Valence, to negotiate the crown of Poland for her son the Duke of Anjou. Cujas recommended Scaliger to the bishop as one of his retinue. On the 22nd of the fatal month of August, 1572, Scaliger, who happened to be at Lyons on business—[he was arranging publication of his Appendix Virgiliana]—received notice to meet Monluc at Strasbourg. He set off, taking the route through Switzerland, and slept at Lausanne on the dreadful night [ie early morning] of the 24th, ignorant of the tragedy then enacting in Paris. Not till he reached Strasbourg did he learn the horrid news. The other members of the embassy had already arrived at the rendezvous, but Monluc did not make his appearance. Disconcerted by the failure of their chief, and fearing to remain so near the French frontier, while alarming accounts were hourly coming in of the fury of the Catholic populace in the provincial towns, the party determined on dispersing. Scaliger was too glad to regain the shelter of Swiss territory. He bent his steps, naturally, to Geneva. (Pattison 153-154)

Scaliger was made a citizen of Geneva in September, and at the end of October he was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the Calvinistic Academy—a post he accepted very reluctantly. Over the course of two years, he delivered lectures on the Organon of Aristotle and the De finibus of Cicero. But the life of a professor did not appeal to him. Scaliger’s passion was ever to learn, not to teach.

Scaliger returned to France via Basle in the late summer of 1574, following the conclusion of the Fourth War of the Huguenots. For the most part, he spent the following twenty years of his life in the service of Chasteigner (1574-93). The Wars continued to rage during this period, and Scaliger and his patrons were constantly on the move throughout the provinces of Poitou, Touraine, La Marche, and Limousin. In times of peace, they moved from one château to another. In times of war, they retreated to the Château du Lion, Chasteigner’s stronghold at Preuilly-sur-Claise in Touraine. Scaliger’s library was kept at the Château d’Abain in Thurageau, another Chasteigner stronghold in Poitou, of which only a tower survives. Other Chasteigner strongholds included the Château de Chantemille near Ahun in La Marche, the Château de Touffou on the Vienne in Poitou, the Château de Malval in Marche, and the Château de La Roche-Posay, of which only the 11th-century donjon survives. And this list does not come close to the full tally of places in which Scaliger dwelt, if his voluminous correspondence is any guide (Wild 116).

During these two decades, Scaliger made a number of trips outside the Chasteigner domains: in 1581 he visited Cujas at Bourges : in 1583 he was at Nérac, at the court of the King of Navarre, the future Henri IV of France : in 1586 he was in Provence (Pattison 158-159) : he visited his native Agen in 1583 and 1584 : in 1583 he visited Périgueux with another Huguenot, the lawyer and scholar Pierre Pithou.

Louis was appointed French Ambassador to the Holy See in 1576 and spent the following five years in Rome. Scaliger, however, spent most of these years at Poitiers or the nearby Château de Touffou (Wild 116).

During the first three years of this period (1574-77), Scaliger devoted himself to the subject of textual criticism, taking the Latin works of Sextus Pompeius Festus, Ausonius, Catullus, Tibullus, and Propertius as his subject matter. In his editions of these authors—published in Paris by Henri Estienne—he laid the foundations of modern philology and textual criticism. In place of the subjective and amateurish practices which were still current, he applied objective and scientific principles. Textual criticisms and emendations, he asserted, ought to be justified by the evidence of the manuscripts and other primary sources. Every editorial alteration of a text, no matter how inconsequential, must be rigorously defended.

Scaliger was not the first to apply these principles to textual criticism—among his many predecessors Lorenzo Valla, Angelo Poliziano and Desiderius Erasmus might be noted—but if his precursors laid the foundations of modern philology, it was Scaliger who raised the edifice (Grafton 1983:2-4).

But having revolutionized the study of philology and diorthotic criticism, Scaliger abruptly abandoned the field and struck out along an entirely new path. His interest in a fresh field of study had been piqued to such a degree that he would devote the remainder of his life to its exploration:

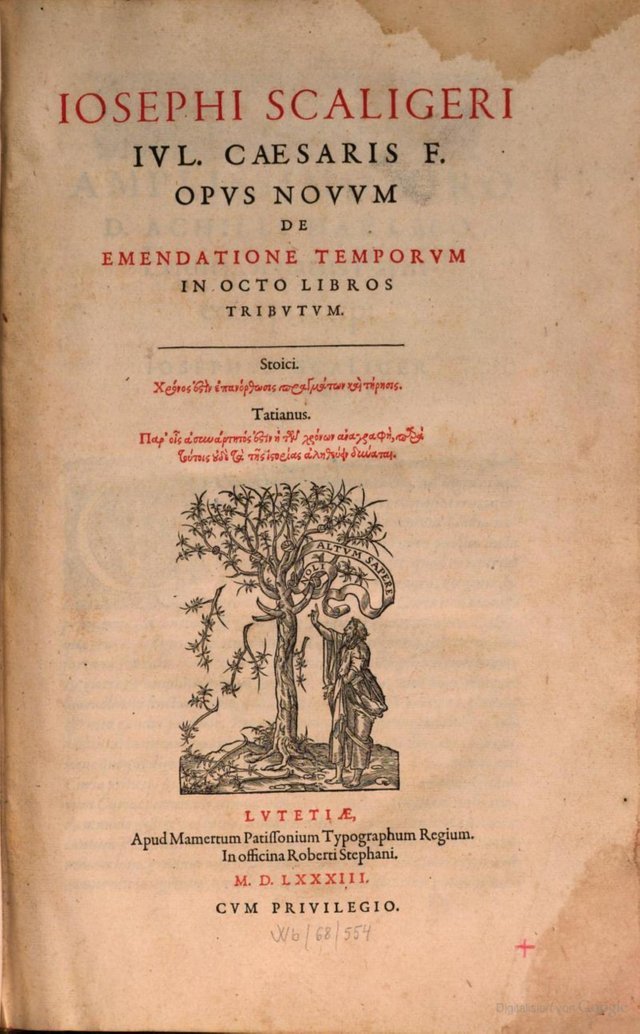

He turned instead to a project so titanic, so stupendous in the amount of labor involved, that no one except a genius of the highest order would have dared even to attempt it. This was nothing less than to assemble, correct, and coordinate all the systems of chronology of the ancient world—Greek, Roman, Hebrew, Egyptian, Ethiopic, Babylonian, Phoenician, Persian, Arabic, Syrian—each with its own manifold variations, and to equate them all according to the newly discovered astronomical principles established by Copernicus and Tycho Brahe. In partial preparation for this tremendous task he produced in 1579 an edition of the five extremely difficult books on astronomy by the Latin poet Manilius, solely with the purpose of acquiring an intimate first-hand knowledge of the astronomical theories of the first century after Christ and their relations to the new science. In four years more this superhuman task was done, and in 1583 appeared the huge folio volume entitled De Emendatione Temporum, or “Treatise on the Correction of Chronology.” “Of this work,” said Daniel Heinsius in his funeral oration on Scaliger, “no one man was ever competent to judge without assistance.” (Blake 87-88)

According to his biographer, Jacob Bernays, Scaliger’s edition of Manilius was not carried out as preparation for his chronological studies. Rather, in preparing his commentary on Manilius, he was obliged to study ancient sources on astronomy and chronology, and this research convinced him of the need for a comprehensive treatment of dates and calendars (Bernays 49). Scaliger’s latest biographer, Anthony Grafton, however, has questioned both interpretations, pointing out that chronology had been on Scaliger’s mind long before he ever conceived of De Emendatione Temporum (Grafton 1993:22-25). In August 1573, about four years before he discovered Manilius, Scaliger set about editing three classical texts that dealt with the astronomical basis of the Roman calendar—the Saturnalia of Macrobius, the Noctes Atticae of Aulus Gellius, and the De Die Natali of Censorinus—although none of these ever came to fruition (Grafton 1993:36).

With De Emendatione Temporum, Scaliger created de novo the science of chronology. He was the first philologist to apply the modern astronomy of Copernicus and Tycho Brahe to the study of ancient history and chronology—in 1606 he even corresponded with Johannes Kepler on the subject. In the fifth of the seven books that comprise his masterpiece, he explained in his own words his purpose for undertaking such a work:

Thus far we have not only described the years and the civil dates of all nations insofar as we have been able to rescue them from the perpetual silence of oblivion, but also have prepared the way for the ready comparison and coordination of these systems with the Julian and civil calendar of our day. There remains the task of bringing home, so to speak, by means of some methodical guide, a chronology which wanders far over all the earth, and strays like some errant stranger back to the beginnings of earliest antiquity, so that he who shall read the records of antiquity, their annals and holy days, shall at length be enabled to know where he stands, and that thus by the instructive power of these assembled dates we may place before his intellectual vision, as it were, a mirror to reflect the epochs of all time. (Scaliger De Emendatione Temporum 5)

Scaliger spent the next ten years—1583-93—revising and expanding De Emendatione Temporum (literally, The Amendment of the Times). During this time, he was relentlessly attacked by rival scholars and browbeaten by the Jesuits, who were determined to reconvert him to the Catholic fold. In the Wars of Religion, this decade was marked by violence and instability. Scaliger later lamented that he spent more time running from château to château than he did studying. He even referred to the region of eastern Poitou to which he was largely confined as Arabia deserta (Grafton 1993:361).

Scaliger is almost a solitary instance of a man who gave up his life to study, without being attached to a university. He was not married. His personal wants were few, and provided for by the liberality of his friend La Roche-Pozay. The remains of his mother’s fortune enabled him to provide himself with the most necessary books. He found himself thus, in the maturity of his powers and the fulness of his knowledge, enabled to give up his undivided mind to literature, to grasp it as a whole, and so to conceive and execute a series of master-works, distinguished by the comprehensiveness of their range from the fragmentary patchwork of the commentators, and by the fresh life of genius which pervades them from the dull compilations of erudite antiquaries. (Pattison 159-160)

In 1593, Scaliger took up the post of Professor of Roman History and Antiquities at the University of Leiden in the Dutch Republic. This post had been left vacant by the departure of Justus Lipsius in 1590, and the Curators of the University had spent the following three years headhunting Scaliger for the post. Initially he declined the offer, being reluctant to exchange Arabia deserta for a post in which all his time would be taken up with teaching. But he finally agreed to accept the position upon the stipulation “that his time should be left completely free for study and writing.” This condition was granted by the Curators “with instant readiness, so great had his reputation grown” (Blake 89).

His reception at Leiden was all that he could wish. A handsome income was assured to him. He was treated with the highest consideration. His rank as a prince of Verona was recognized. Placed midway between The Hague and Amsterdam, he was able to obtain, besides the learned circle of Leiden, the advantages of the best society of both these capitals. For Scaliger was no hermit buried among his books; he was fond of social intercourse and was himself a good talker. (Chisholm 285)

Scaliger spent the remaining fifteen years of his life in the Dutch Republic, despite finding the climate inclement, the city life disagreeable, and the inhabitants cold and boorish (Grafton 1993:374-375). Among those who studied under him were the jurist Hugo Grotius, the geographer Philipp Clüver, the philologists Franciscus Dousa, Johann von Wowern Geverhart Elmenhorst and Heinrich & Friedrich Lindenbrog, and the classical scholar Daniel Heinsius, who became not only his favourite pupil but also his closest friend. Scaliger taught his students by guiding their own research rather than by tutoring them in their chosen fields:

Wilhelm Dilthey singled Leiden out as the first truly modern university because it made research and training in research a normal part of its business. Scaliger was largely responsible for both innovations. (Grafton 1993:392)

Scaliger gradually warmed to Leiden, and came to believe that the Athens of the ancient Greeks had been transported to this little corner of Batavia, where letters were free to flourish once again (Grafton 1993:393).

Eusebius and the Thesaurus Temporum

Between 1597 and 1599, Scaliger worked on a new edition of Manilius’s Astronomica. As soon as he had completed this, he embarked on another titanic project, one which would take him more than half a dozen years to complete:

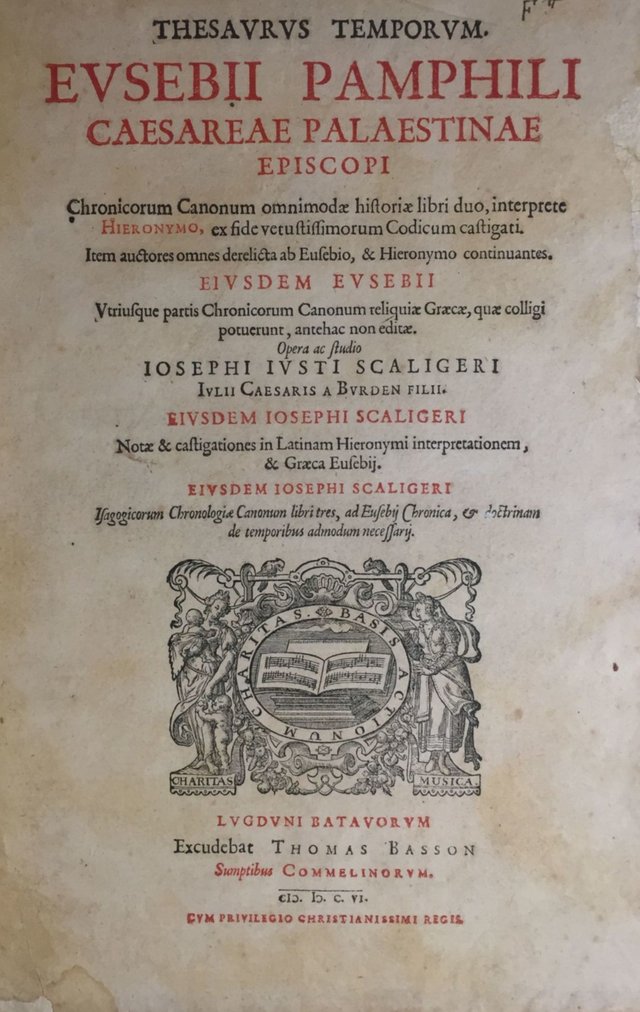

Meantime the synoptic presentation of world-history which he had proposed was slowly taking shape. Seeking for some central point about which he might group the far-flung researches of his De Emendatione Temporum, he selected the so-called Chronicle of an ancient worker in the same field as himself, Eusebius, the fourth-century Bishop of Caesarea. The original Greek Chronicle of Eusebius had completely disappeared except for a few recognizable quotations in Byzantine authors, and a highly abridged Latin rendering by St. Jerome. Scaliger now set himself the incredible task of recovering from every conceivable ancient source the lost material of the original chronicle, and of restoring it completely in the Greek form of the original. From his study of the Byzantine fragments he conceived the boldly original idea that Eusebius’ work had consisted of two books, and that St. Jerome had abridged and translated only the second, which, being in the form of chronological tables, was the more practically useful of the two. The first book Scaliger decided had contained documentary epitomes of the Greek writers on Oriental history and it was this which he particularly determined to recover. Yet despite his microscopic examination of all ancient literature for evidences of Eusebian fragments, his collection was meagre and his task seemed doomed to failure. Then, with the extraordinary good fortune which so often smiles upon bold endeavor, he came in 1601 upon the track of a hitherto unknown Byzantine chronicler of the ninth century, the monk George, syncellus, or patriarch’s coadjutor, at Constantinople. To Scaliger’s unbounded delight this work, now well known as the Chronicle of Syncellus, proved to contain far more of the original Eusebius than all the previous fragments which he had collected with so much labor. Thus in the year 1606 he published his restored Greek Eusebius as the central point of his two huge folio volumes of the Thesaurus Temporum—or “Treasure-House of Dates”—in which every extant relic of Oriental, Greek, and Roman chronology is arranged in due order and restored to intelligibility. This is the work in which, as Professor Garrod of Oxford remarked only a few years ago, “one half of modern scholarship has its forgotten source.” (Blake 89-90)

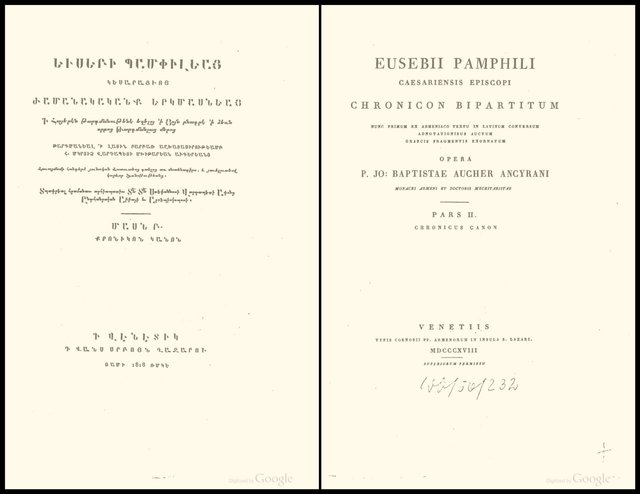

In 1818, a complete edition of Eusebius’s Chronicle was published in Venice from a 12th-century manuscript that contained a copy of an anonymous 5th-century translation of the work into Armenian. This edition proved that the Chronicle had consisted of two books and that Jerome had translated only the second of them. Scaliger’s reconstruction of the first book was, of course, imperfect—how could it not be?—but much of its content was found to be largely correct. If Scaliger had erred, it was in leaning too heavily upon Syncellus. Much of what Syncellus had taken from Sextus Julius Africanus Scaliger had mistakenly attributed to Eusebius (who flourished about a century after Africanus), believing that Eusebius’s Chronicon was an epitome of Africanus’s, and George Syncellus’s an epitome of Eusebius’s (Grafton 1993:544):

... the Armenian text is laid out in two books, one discursive and one tabular. And the first book, for all the differences of detail, does contain many of the constituent texts Scaliger was certain should be there ... True, the Armenian Eusebius has more to say than Scaliger’s Greek one about historical source-criticism and chronological method. And his Babylonian and Egyptian records are presented in their entirety in individual chapters, not chopped up and interspersed in chronological sequence. But these flaws, if flaws they are, hardly outweigh Scaliger’s extraordinary recovery of the general form and content of a major book by a major ancient author, the existence of which no previous scholar had suspected. (Grafton 1993:547-548)

To his reconstruction of Eusebius’s Chronicon Scaliger appended the Historion synagoge [Collection of Histories], a compilation of historical fragments from ancient and medieval sources. The best known of these is the Olympiadōn Anagraphē [Register of Olympiads], which Scaliger reconstructed from several disparate sources. It is often mistaken for an ancient text. The last three books of the Thesaurus Temporum comprised Scaliger’s final treatise on the subject of chronology: the Isagogici Chronologiae Canones, or Introductory Rules of Chronology. This synthesis of a lifetime’s study of the science and practice of chronology is Joseph Scaliger’s final verdict on the subject.

Final Years

The last three years of Scaliger’s life were beset by vituperative attacks upon his person, his scholarship and his pretensions to aristocracy by two Jesuit writers, Carolus Scribani and Caspar Schoppe—the latter a convert from Protestantism. Scaliger was certainly not immune to criticism, even as he reigned supreme over the learned world from his “throne” in Leiden, where he was lauded as Princeps Litterarum (Prince of Letters: Pattison 134) and Aquila in Nubibus (An Eagle among the Clouds: Bernays 8):

Scaliger had made numerous enemies, He hated ignorance, but he hated still more half-learning, and most of all dishonesty in argument or in quotation. Himself the soul of honour and truthfulness, he had no toleration for the disingenuous arguments and the mis-statements of facts of those who wrote to support a theory or to defend an unsound cause. His pungent sarcasms were soon carried to the persons of whom they were uttered, and his pen was not less bitter than his tongue. He resembles his father in his arrogant tone towards those whom he despises and those whom he hates, and he despises and hates all who differ from him. He is conscious of his power, and not always sufficiently cautious or sufficiently gentle in its exercise. Nor was he always right. He trusted much to his memory, which was occasionally treacherous. His emendations, if frequently happy, were sometimes absurd. In laying the foundations of a science of ancient chronology he relied sometimes upon groundless, sometimes even upon absurd hypotheses, frequently upon an imperfect induction of facts. Sometimes he misunderstood the astronomical science of the ancients, sometimes that of Copernicus and Tycho Brahe. And he was no mathematician. (Chisholm 285)

Scaliger’s pride in his own supposed nobility would be his downfall:

A nobleman could not owe so much of his eminence to others. He could not, bear to be corrected or disowned by those whom he had chosen to follow—and from whom he had decided to borrow. Hence the curious, jagged trajectory of Scaliger’s intellectual life, as he appropriated method after method, used them in novel combinations, and then found himself driven to reject the great men who betrayed him, claimed their property when they saw it in his work, or criticized his applications of it as illegitimate. Scaliger, the best of students, was the worst of disciples. He thrust his former masters away as forcefully as he had once clasped them to him. (Grafton 1983:227)

It was difficult enough for Scaliger’s detractors to acknowledge him as a prince of letters : to acknowledge him as an actual prince to boot was quite impossible. In 1605, Scribani took a sledgehammer to Scaliger’s reputation with his Amphitheatrum Honoris, a diatribe of insults levelled at Scaliger and other Calvinists. But while Scribani’s chosen weapon was the maul, Schoppe wielded the scalpel:

Scaliger’s weak point was his pride. In 1594, in an evil hour for his happiness and his reputation, he published his Epistola de vetustate et splendore gentis Scaligerae et J. C. Scaligeri vita [Epistle on the Antiquity and Splendour of the Scaliger Family and A Life of J. C. Scaliger]. In 1607 [Caspar Schoppe], then in the service of the Jesuits, whom he afterwards so bitterly libelled, published his Scaliger hypobolimaeus (“The Supposititious Scaliger”), a quarto volume of more than four hundred pages, written with consummate ability, in an admirable and incisive style, with the entire disregard for truth which [Schoppe] always displayed, and with all the power of his accomplished sarcasm. Every piece of scandal which could be raked together respecting Scaliger or his family is to be found there. The author professes to point out five hundred lies in the Epistola de vetustate of Scaliger, but the main argument of the book is to show the falsity of his pretensions to be of the family of La Scala, and of the narrative of his father’s early life. “No stronger proof,” says Mark Pattison, “can be given of the impressions produced by this powerful philippic, dedicated to the defamation of an individual, than that it has been the source from which the biography of Scaliger, as it now stands in our biographical collections, has mainly flowed.” (Chisholm 285, Pattison 191-192)

Scaliger published a riposte to Schoppe’s attack—his final work, the Confutatio Fabulae Burdonum [A Refutation of the Asses’ Fables] of 1608—but the damage was done. Scaliger was a broken man. His health declined when he was obliged to move from his comfortable lodgings on the Breestraat to a new house that was small and damp. Nevertheless, he continued to work, revising the Thesaurus Temporum and copying all the material in foreign languages from his personal library. He continued to take an interest in the affairs of the University.

The winter of 1607-08 was one of the coldest of the Little Ice Age. Scaliger survived it, but he never recovered from the blow. Plans to collaborate with Heinsius on a new edition of Plautus had to be abandoned, and by November 1608 he was so ill that he made his will (Grafton 1993:749-750).

Joseph Juste Scaliger died of dropsy in Leiden on 21 January 1609. He was sixty-eight years of age. He was buried in the Vrouwekerk (Church of Our Lady), a Huguenot church in the centre of Leiden, of which only a few ruins remain. In 1819, when the Vrouwekerk was demolished, his remains were transferred to Pieterskerk, a few hundred metres away.

Scaliger was not a wealthy man. He once remarked to his colleagues: Ever since my father’s death, I have lived on charity (Pattison 219). His mother was relatively rich at the time of her death, but after Scaliger’s elder brother and the lawyers at Agen had taken their shares, there was little left for the rest of the family. Scaliger’s portion of the estate was quickly exhausted on books (Pattison 229), though he once told his students at Leiden that had he been a truly rich man, he would have spent his money on travel, not books (Grafton 1993:108). A pension of 2000 francs that Henri III of France had conferred on him was never paid.

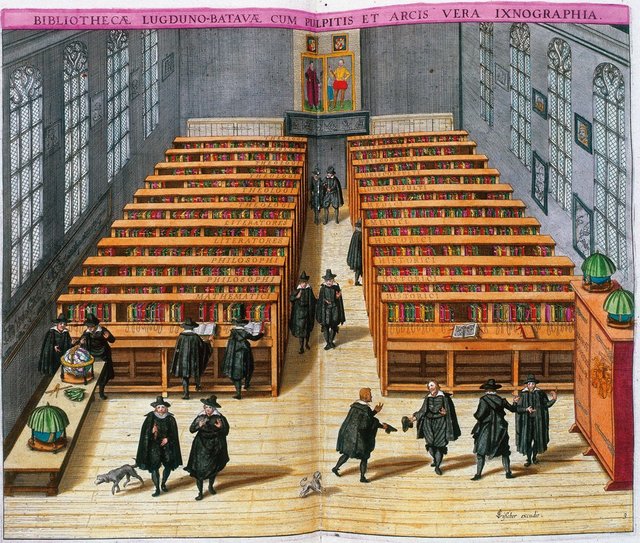

On his death, he left a library of over 2000 manuscripts and printed books. His friends and colleagues were invited to take their pick of the “western” books—ie those printed in Greek and Latin. The remaining printed books in these two languages—1801 volumes (van Selm 118)—were bequeathed to his valet, Jonas Rousse, who auctioned them off in 1609 to provide himself with a pension. The rest—All my books in foreign languages: Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopic and his western manuscripts—were left to Leiden University. These 210 volumes formed the heart of the university’s Library. Many of his Greek and Latin printed books eventually found their way back to Leiden University, where Daniel Heinsius shelved them in the library in the so-called Arca Scaligeri—a tall cupboard (van Ommen 146 ff):

Scaliger begins his will with a vigorous profession of his Protestant faith. He goes on to appoint his sister Anne della Scala as his heiress to all his goods in Agénois. He bequeathes his money and movables in Leiden to his valet Jonas Rousse, except for some sums of money which he destines for his chambermaid Anna and the poor of the Walloon church of Leiden. He assigns a number of valuables to prominent persons, friends and acquaintances, among whom Isaac Casaubon, Carolus Clusius and Daniel Heinsius.

With regard to his books Scaliger disposed as follows:

– All Oriental books (‘all my books in foreign languages’), both manuscript and printed, were bequeathed to the University of Leiden.

– The Greek and Latin manuscripts, including those of Scaliger’s own works, his adversaria and those of some works by his father, were also assigned to the University Library.

– A number of non-Oriental printed books, listed in a codicil, were set apart; from these, a small number of friends, also mentioned in the codicil, were entitled to choose and keep the books they wanted. Scaliger accorded this favour to Mylius, Heinsius, Baudius, Gomarus and some others. Each of them was allowed to take his turn when his name came round again on the list and to select a volume he wanted; each of them was allowed to choose several times.

– The books that remained had to be auctioned; the proceeds were to go to Jonas Rousse. (Vrolijk & van Ommen 39-41 [Exhibit 7])

The remainder of his estate he bequeathed to his sister Anne de Lescale de Vérone, who was still living on their mother’s estate at Vivès (Vérone) in the parish of Montbran, just outside Agen (Jonge 249, 256 : Hall 161).

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Jacob Bernays, Joseph Justus Scaliger, Wilhelm Hertz, Berlin (1855)

- Warren Blake, Joseph Justus Scaliger, The Classical Journal, Volume 36, Number 2, Pages 83-91, The Classical Association of the Middle West and South, Inc, Chicago (1940)

- Hugh Chisholm (editor), Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume 24, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1911)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 1, Textual Criticism and Exegesis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1983)

- Anthony Grafton, Joseph Scaliger: A Study in the History of Classical Scholarship, Volume 2, Historical Chronology, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1993)

- Vernon Hall, Jr, Life of Julius Caesar Scaliger, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 40, Number 2, Pages 85-170, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia (1950)

- Daniel Heinsius (editor), Epistolae [All the Letters that Could Be Found of the Most Illustrious Man, Joseph Scaliger, Son of Julius Caesar Bordone, Collected and Edited for the First Time], Bonaventura & Abraham Elzevir, Leiden (1627)

- Henk Jan de Jonge, The Latin Testament of Joseph Scaliger, 1607, LIAS: Journal of Early Modern Intellectual Culture and its Sources, Volume 2, Pages 249-263, Academic Publishers Associated, Amsterdam (1975)

- Mark Pattison, Joseph Scaliger, in Essays, Volume 1, Pages 132-243, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1889)

- George W Robinson (translator & editor), Autobiography of Joseph Scaliger, with Autobiographical Selections from His Letters, His Testament, and the Funeral Orations by Daniel Heinsius and Dominicus Baudius, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1927)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, De Emendatione Temporum, First Edition, Mamert Patisson, Paris (1583)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Epistola de Vetustate et Splendore Gentis Scaligeræ et Iulii Cæsari Scaligeri Vita, Francis van Ravelinghen, Plantin Press, Leiden (1594)

- Joseph Juste Scaliger, Thesaurus Temporum, Johannes Janssonius, Amsterdam (1658)

- Philippe Tamizey de Larroque (editor), Lettres Françaises Inédites de Joseph Scaliger, Alphonse Picard, Paris (1884)

- Kasper van Ommen, “Tous mes livres de langues estrangeres”: Reconstructing the Legatum Scaligeri in Leyden University Library, Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, Volume 34, Number 3, Pages 143-184, Victoria University in the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario (2011)

- Bert van Selm, A List of Dutch Book Auction Sale Catalogues Printed before 1611, Quaerendo, Volume 12, Issue 2, Pages 95-129 Brill Publishers, Leiden (1982)

- Arnoud Vrolijk & Kasper van Ommen, ‘All my Books in Foreign Tongues’: Scaliger’s Oriental Legacy in Leiden 1609-2009., Kleine Publicaties van de Leidse Universiteitsbibliotheek, Number 79, Leiden University Library, Leiden (2009)

- Francine Wild, Le Prima Scaligerana: Registre d’une amitié savante, Albineana, Cahiers d’Aubigné, Number 7, Pages 115-130, Classiques Garnier, Paris (1996)

Image Credits

- Joseph Juste Scaliger: Nicolas Eustache Maurin (painter), François-Séraphin Delpech (engraver), Bibliothèque de Genève, Public Domain

- Joseph Juste Scaliger (Jan Cornelis Woudanus): Jan Cornelis Woudanus (artist), Icones Leidensis, Number 31, Senate Chamber, Academy Building, Leiden University, Public Domain

- Rue Saint-Georges, Agen: Antique CDV Photograph of Agen, Rue Lamennais, Ancienne Rue St-Georges (c 1890), Public Domain

- Ancienne Église Saint-Hilaire d’Agen: KoS (photographer), Public Domain

- Jean Dorat: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica Digital Library, Public Domain

- Ancient Street Plan of the Collège de Tréguier: Adolphe Berty, Topographie Historique du Vieux Paris, Volume 6, Région centrale de l’Université, Plate 12, Between Pages 286-287, Imprimerie Nationale, Paris (1897), Public Domain

- The Collège de Tréguier and its Environs circa 1550: Olivier Truschet & Germain Hoyau, Plan de Paris, Basle (1552), Public Domain

- Louis Chasteigner: Jean Picart (engraver), The British Museum, 1910,0610.39 London, Public Domain

- La Roche-Posay: © GFreihalter, Creative Commons License

- The St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre: François Dubois (artist), Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland, Public Domain

- South Wing of the Collège Calvin: Mourad ben Abdallah (photographer), Public Domain

- Château du Lion (Preuilly-sur-Claise): © DoucF (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Château d’Abain (Thurgeau): © Jm.durand, Creative Commons License

- De Emendatione Temporum (1583): Joseph Justus Scaliger, De Emendatione Temporum (1583), Titlepage of a Copy in the Bavarian State Library, Munich, Public Domain

- Thesaurus Temporum (1606): Joseph Justus Scaliger, Thesaurus Temporum (1606), Titlepage of a First Edition, Leiden, Public Domain

- Armenian Translation of Eusebius’s Chronicon (1818): Giovanni Battista Auchèr (translator & editor), Eusebii Pamphili Chronicon Bipartitum Graeco-Armeno-Latinum, Part 2, Auchèr, Venice (1818), Public Domain

- Charles Scribani: Anthony van Dyck (artist), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Public Domain

- Caspar Schoppe: Portrait of Kaspar Schoppius (cropped), Peter Paul Rubens (artist), Palatine Gallery, Pitti Palace, Florence, Public Domain

- Joseph Juste Scaliger (Calbet): Antoine Calbet (artist), La Salle des Illustres de l’Hôtel de Ville d’Agen, Agen, Public Domain

- The University of Leiden Library in 1610, with the Arca Scaligeri (Right Foreground): Willem van Swanenburg (engraver), after Johannes Cornelisz Woudanus, Stedeboeck der Nederlanden, Willem Blaeu, Amsterdam (1649), Public Domain

- Scaliger’s Epitaph: © Pieterskerk Leiden, Fair Use

- The Pieterskerk, Leiden: © Johan Bakker, Creative Commons License

- Map of 16th-Century France and Its Environs: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, from Adolphus William Ward et al (editors), Cambridge Modern History Atlas, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1912), Public Domain

Online Resources