The Immense Journey, by Loren Eiseley (part 2)

Last time I mentioned how scientific fights are rarely truly settled. They tend to pop up again, in slightly different form, whenever new evidence is discovered. In The Immense Journey, Loren Eiseley discusses a couple of these situations, which were both being publicly debated in the mid 1950s. He reaches back to show how history had shaped those debates, and I'll show how they're still going on now.

In “The Great Deeps,” he details the hunt for the earliest forms of life on the abyssal plain, those parts of the oceans below the continental shelves, where sunlight never penetrates. During the 1800s, a big part of the scientific community was convinced that somewhere down there, the nonliving slime was still giving birth to new species. They also thought that most of the species from the fossil record were still alive, haunting the edges of the world, where later, better creatures had driven them. It was all very Victorian. Eiseley, from the 1950s, dismisses this, saying that sunlight was necessary to provide the energy of life, but he didn't know about black smokers, those deep sea volcanic vents that drive thriving communities of bacteria with heat energy. The deep-sea origin of life is again being seriously considered, both here and on the ice moons of Saturn and Jupiter, which are so far from the sun that its light would be less useful.

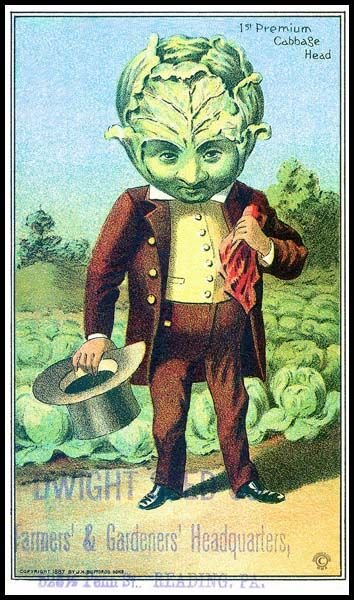

From a vintage vegetable catalog.

image source

In “Little Men and Flying Saucers,” Eiseley talks about the human tendency to see ourselves as the pinnacle of evolution. He cites a number of authors over hundreds of years who argued either that humans were alone in the universe, or that (like on Star Trek) every planet would evolve towards intelligent humanoids. My favorite bit of snobbery towards SF:

“In the modern literature on space travel I have read of cabbage men and bird men … I have been reading about a man, Homo sapiens, that common Earthling, clapped into an ill-fitting coat of feathers and retaining all his basic human attributes including an eye for the pretty girl who has just emerged from the space ship … if this is all we are going to find on other planets, I, for one, am going to be content to stay at home. There is more than enough of that sort of thing down here.”

What we call SF entertainment today was serious scientific debate in the 1850s, and continues through the SETI radio telescope research of the 1970s right up to the microbial astrobiology of today. We point telescopes at distant planets, hoping to find the chemical signatures of life, written in the spectrum of the light they reflect from their atmospheres. Are we alone, or are we not? Without data, we endlessly argue our hopes and fears as hypotheses. What Eiseley was right about was this: if we do find something, it won't be humanoid.