Gandhi the Atypical Ascetic Part 4: An original analysis of Gandhi's REMARKABLE Fasting, and its spiritual purpose.

Ladies and Gentleman get some NOS in your gas tanks--this is the MEAT of my working thesis...how Gandhi's later life during his call for civil rights in India was an "atypical" way to explore his personal path to TRUTH.

What TRUTH do WE ("The royal 'we'...you know, the editorial..." I spot a Big Lebowski line in there somewhere...) speak of?

We are talking about about "unchecked aggression."

No, just joking... We are talking about how this skinny fellow, Gandhi, was seeking to find the Ultimate Reality! ( You know...Moksha, liberation, enlightenment). The strange thing is, he did it though staying involved in society and protesting. He didn't try it like some crazy guy going off into the woods to find his soul...and that is the amazing part!

Haha I hope you like my-- easy DUDE-- way of explaining Part 4 of my religion thesis on Gandhi. In fact, I am just getting the hang of this whole blogging thing...

Soon, I will shift more of my focus on health topics. As a senior in medical school, it is fun as well, and I think it will relate to more people. I am proud of my religious projects I slaved over in college! As a double major in both religion and biology in college, I am happy to share it with Steem. It is hard to believe I wrote this essay 4 years ago!

This Gandhi masterpiece series has actually made zero cents so far, haha. But I have seen some interest so I am going to keep PUMPING this for all it is worth!

Now off "THE DUDE" language and let's get into real nerd mode. Let's actually get really deep into this like all my college professors did. BANG. Still with me....good.

In Part 1, I set the stage for my research paper by going into why I am out to prove that Gandhi is, indeed, an atypical ascetic.

See link below:

https://steemit.com/religion/@tfeldman/understanding-gandhi-as-an-atypical-ascetic-part-1

In Part 2, I write about Gandhi's life as a child and young adult. It goes into how he fit the "Hindu role" of a "householder."

See link below:

https://steemit.com/religion/@tfeldman/understanding-gandhi-as-an-atypical-ascetic-part-2

In Part 3, I write about Gandhi's VOW and transition away from the "householder" stage to abstain from sex later in life, a very Hindu/ascetic theme.

See link below:

Now to Part 4! It's the--MEAT of my paper. It's the support of why I think Gandhi was an atypical ascetic by staying involved for the rights of humanity in India. GET READY FOR THE WRATH OF A QUIET/ PEACEFUL GANDHI!

Mahatma Gandhi: The Atypical Ascetic

Part IV: An Atypical Ascetic Through Civil Disobedience

In the later part of Gandhi’s life when he returned to India after having spent many years practicing law in South Africa, his mind and body had been attuned to ascetic philosophies. The India he returned to, however, was split physically and spiritually. Mill workers were starving and their labor conditions were rough. There was pure animosity towards the “untouchables” from the caste system. There was also horrific hatred between the Muslims and Hindus in India.

With all of this hatred and civil injustice, Gandhi felt he had a mission to unify India. He would embark on extreme physical renunciations to try and accomplish this unity. It is very atypical of an ascetic to be this focused on worldly concerns while trying to “free” his or her own spirit, but Gandhi felt that this was the best way to discover “Truth.” In other words, his atypical behavior that is uncharacteristic of most ascetics was his vehicle to God.

Gandhi’s unique, ascetic behavior cannot be put any better than when Mandelbaum proclaims, “As a renowned leader, Gandhi is by definition atypical,” which demonstrates that even in the political sense, Gandhi was atypical (83).

His political side also coincides with the religious as well. One might ask, why did he find that staying in society was the best way to find Ultimate Truth? Through his perception of God, this question can be explained thoroughly. Gandhi declares,

“Hence I gather that God is Life, Truth and Love. He is Love…the safest course is to believe in the moral government of the world” (Fischer 108).

If Gandhi believes that God is these three things, then he must have strived to find love in a split world of anger and greed. By renouncing hatred in the form of hunger strikes, he was able to attempt to uncover love, which for him, is God. He also discusses that because humans lack ultimate knowledge, the best way to cultivate love is through a moral government. If Gandhi could accomplish this, he would be acting in truth since Love for him is God. On the other hand, if he went into the forest, he would not be able to cultivate this Love in the world.

Now that it is clear that his intentions of self-realization necessitated the push for civil rights, one must understand why it is atypical for an ascetic to act in this fashion. A great example of why Gandhi is “atypical” is that he does not fit into broad definitions of asceticism that Max Weber presents in The Sociology of Religion. Gandhi most closely resembles what Weber calls inner-worldly asceticism when he describes this ascetic as a “rationalist…but also in his rejection of everything that is ethically irrational” (168). This part of his definition coincides with Gandhi very well, but it misses key elements that Weber would classify under other types of ascetics. Weber’s best example of inner-worldly asceticism is the ideology of Protestants, and he dedicated an entire book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, to this end.

He claimed that many enterprises are Protestant based due to the tradition in which making money was seen as a test of one’s will to God (Weber 108-109). This notion of an inner-worldly ascetic is almost purely internalized and their ascetic actions are just common practices of society (capitalism). Gandhi, on the other hand, did not participate in ordinary practices like Protestants did, and instead, Gandhi focused on fasting protests, which was not an ordinary activity in society. These physical renunciations are more characteristic of ascetics who leave society. The one thing that does match with inner-worldly ascetics was Gandhi’s need of society to bring him closer to God. In other words, Gandhi is “atypical” since he does not fit into ordinary definitions of asceticism. However, he still fits the general definition of what an ascetic identity is even though he does not fit well under Weber’s subcategories of asceticism.

Gandhi arrived back in India a different man, a man who was going to practice self-disobedience in order to unite the people of India. Gandhi spent of total of 2,089 days of jail time in India (Fischer 148). Much of this time in jail was due to the Salt Tax, which the British implemented, and many Indians could not afford it. Gandhi was set for his country to make their own salt production, which finally led him to getting arrested.

As mentioned earlier, Love to him is God, so his love for his country led him to protest. Fischer claimed that “Gandhi loved it in jail (100). Gandhi recalls in his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, that jail was a vehicle that forced one to practice “self-restraint” (325). This is an interesting outlook on jail, and it reveals that Gandhi was still trying to spiritually develop through protest. Protesting often lead him to jail, but in a way, it only made him purer.

His pureness would be signified by his even more drastic measures of self-restraint in the midst of the public eye. The clearest examples of Gandhi’s atypical asceticism was his method of using hunger strikes as a tool for spiritual elevation while simultaneously trying to unify India. Gandhi did not use hunger strikes against the British; however, he did fast as a method to unify his fellow Indians. One major event was his “fast till death” in protest to how “untouchables” were treated and not represented in Congress. This fast, while there were others, was the “fast until death” if conditions did not turn. His last meal before the fast was simply water with honey and lemon juice (Fischer 117). When people were insisting on his reasoning for his extreme actions he proclaimed,

“No civilized society can thrive upon victims whose humanity has been permanently mutilated…we insult our own humility by insulting man where he is helpless “(Fischer 118).

Gandhi was fasting to eradicate a society that victimized innocent people. When he declares that one insults his or her own humility by disrespecting others, it shows that his countrymen needed to treat others well in order to cultivate the True Spirit. Gandhi saw that the animosity towards the untouchables would not be any easy thing to eradicate, but eradicating desires of the flesh is also not an easy accomplishment. His resolution was even more drastic than most ascetics begging for food because he ceased to eat, and his life was on the line.

The epic fast lasted six days in 1932, and Gandhi only had limited amounts of water during the fast (Fischer 119, 121). Gandhi’s demands to have the “untouchables” represented in Congress and to be given more respect in society was accomplished with the Yeravada Pact. Conditions for the “untouchables” were not perfect, but their statuses definitely were improved. Through Gandhi’s ascetic hunger strikes, traditional India has been reconstructed to value untouchables with respect too. Gandhi was atypical in that he became more spiritual by morally cultivating society versus fleeing from it.

Gandhi, as mentioned earlier, participated in numerous hunger fasts. One fast to unite Muslims and Hindus as friends even lasted 21 days (Lal 173). However, this was not considered the most drastic even though this had the longest duration. There can be two reasons why some of his other fasts were more notable. Firstly, his intake of water decreased with his later fasts. Secondly, his demands to break the fast became harder and harder, which lead people to believe that he could truly die.

The last fast before his assassination is another great example of his atypical nature, which will be covered briefly. One should also note that shortly before his last fast, he fasted again in Calcutta to stop the Hindu’s from killing Muslims once India was free from British rule (Fischer 178). This fast ended in 73-hours, and no act of violence was committed in Calcutta when he ceased his fast. He also said that if the men he spoke to commenced violence in Calcutta he would take an “irrevocable vow,” which would end in his death (Fischer 178).

After this fast, he began his final fast, which was very spiritual in its demands. Gandhi’s last fast in 1948, shortly before his death, required “a reunion of hearts of all communities…from an awakened sense of duty” (Lal 174). In other words, Gandhi would not break the fast unless the internal mindset of India did not change even in the midst of different religious practices. Like usual, his fast was successful, and Hindu’s allowed Muslims to regain their homes in Delphi and they were also allowed to have their mosques reinstated.

The patrician of India that split part of it into Pakistan caused bloodshed for both religious groups. With improvements made, Gandhi said that this was his “greatest fast” (Lal 182). Gandhi could have died on this last fast, but his spiritual power was stronger than his desire to eat. This last fast was also unique in the sense that he insisted on not just keeping peace, but also, to cultivate morality between religious faiths. When he said that people needed to awaken to their duty, there seemed to be religious undertones as well from Hinduism. Many ascetics escape society in order to ease the transition into a higher spiritual state. Even inner-worldly ascetics seem to be focused on their internal selves versus the “lost souls” in society. However, Gandhi saw hope in every disaster. If God is Truth, which is a singular term, then maybe Gandhi felt that he could not reach Moksha unless the populous strived for it as well (seeing the populous as a single entity). Although this logic of using civil disobedience against injustices seem uncharacteristic for ascetics, it still makes sense. One might ask why an ascetic would have a desire to stay so attached to worldly problems? The answer appears to be that Gandhi needed society as a vehicle to cultivate Love. Desires of the world can blind people, but ascetics wondering off into the forest might also be blind to the atrocities that propagate around them. Being blind to society might cause one to not find Truth and Love, which Gandhi proclaimed was his mission. Inner-worldly ascetics, on the other hand, stay in society but internalize asceticism and kind of “go with the flow” of normalcy. Gandhi also externalized his asceticism, like in his last fast, which was uncharacteristic.

Although most scholars agree with Gandhi’s political struggles as actions having ascetic values, there are of course critics to Gandhi’s motives. Rajani Palme Dutt felt that Gandhi used these nonviolent protests as a way to protect the Bourgeoisie in India. Dutt’s views were that Gandhi was not altruistic and used “non-violence” as a clever design to protect landowners in India (Plotkin 1). Some individuals feel that Gandhi was not very spiritual and was only using a religious design to craft what he felt was right. With this logic, Gandhi stayed in society not to cultivate more spirituality, but simply, to protect certain individuals.

Even though these views seem rather radical, it is bizarre that Gandhi made demands that consisted of if “X” is not accomplished then “Y” will happen. It is almost child-like in a way since children are always resilient to their parents when they do not get what they want. However, the “Y” component of his political formula would result in his death. It seems impossible that one is not altruistic if he or she is wiling to die for beliefs, which Gandhi did when he was assassinated.

According to Gandhi’s personal accounts, his beliefs were that he could cultivate Truth through civil rights. Another way to combat this criticism would be to presume that his “atypical” manners lead people to ask questions (be critical) because it is uncharacteristic for a Hindu ascetic to act in these ways. Even if Gandhi’s motives intended to just help the Bourgeoisie and landowners, it still does not explain how he is not altruistic. Whatever his true motives for self-sacrifice in political form were, he still was willing to die and spoke deeply about his actions in a religious, ascetic way.

Conclusion

By looking at the stages of Mahatma Gandhi’s life, one can perceive him as one of the few ascetics who acted in such a manner. To the degree he went to, maybe the only one. Monks have burned themselves alive before, but at the same time, they did not cultivate love in society, as Gandhi was able to do.

In the final pages of Gandhi’s autobiography he declares,

“There is no other God than Truth. And if every page of these chapters does not proclaim to the reader that the only means for the realization of Truth is Ahimsa, I shall deem all of my labor in writing…in vain” (504).

His words echo his atypical, ascetic self. He believed in God, which was Truth. However, it is unique that he believed that the only means of realizing God was through non-violence (ashima) in a society full of turmoil. His non-violence was put to the test when so many he encountered wanted bloodshed. Instead of wanting to kill or fight for love, he passively used self-renunciation to transform the minds of society and to cultivate Love and Truth. It is not that isolating oneself away from the community is violent, but outside of the public eye, there is no violence to test one’s will.

His path to God was atypical because he experimented within society to nurture Truth, which to him, was God. Gandhi can be seen as ascetic because he had the mental capacity for self-renunciation at an early age even though he had not transformed them in a physical sense. Once he made the Brahmacharya Vow, his ascetic tendencies transcended into the physical aspects as well. Although one could characterize his physical and mental tendencies as ascetic, his methods were one-of-a-kind. To attain a higher spiritual state, he had to raise the morale of society simultaneously. One can only wonder if Gandhi would believe that wondering or inner-worldly ascetics could find Truth as well. Maybe there are multiple ways to striver for Moksha, but for Gandhi, it appeared to be through society. There might never be such an individual again, but if one appreciates his life, then trying to understand it is important. Looking through the lens of asceticism, Gandhi has such qualities but in such a unique way. It is amazing that an individual could be altruistic for the world, while at the same time, striving to attain Moksha.

THE END!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

WOW!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Thank you all who have taken the time to read my large essay on Gandhi, and I hope you learned something. Don't forget to read back to the other three parts if you want to kind of "fit the whole thing together"

Follow me if you are interested in health topics, music, science, philosophy/religion!

Works Cited

1) Ashe, Geoffrey. Gandhi. New York: Stein and Day, 1968. Print.

2)Cassian, John. Institutes Book 6. New York: Newman, 2000. Print.

3) Fischer, Louis. Gandhi: His Life and Message for the World. New York: Mentor, 1954. Print.

4) Flood, Gavin. The Ascetic Self: Subjectivity, Memory and Tradition. Cambridge: University, 2004. Print.

5) Gandhi. An Autobiography: the Story of My Experiments with Truth. [S.l.]: Beacon, 1957. Print.

6) Kaelber, Walter O. "A Basic Definition of Asceticism." The Encyclopedia of Religion. 1987. Print.

7) Lal, Vinay. "Gandhi's Last Fast." Gandhi Marg (1989). Web. <http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/History/Gandhi/ghandis%20last%20fast.p df>.

8) Mandelbaum, David G. "The Study of Life History: Gandhi." Current Anthropology 14.3 (1973): 177-206. Print. Plotkin, Michael. "Resistance to the Soul: Gandhi and His Critics." Web. <http://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/soul.htm>

9) Weber, Max. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge, 2006. Print.

10) Weber, Max. "The Sociology of Religion - Max Weber." Google Books. Web. 25 Nov. 2011.<http://books.google.com/books/about/The_sociology_of_religion.html?id= abS61 el-VEMC>.

*Original essay by tfeldman

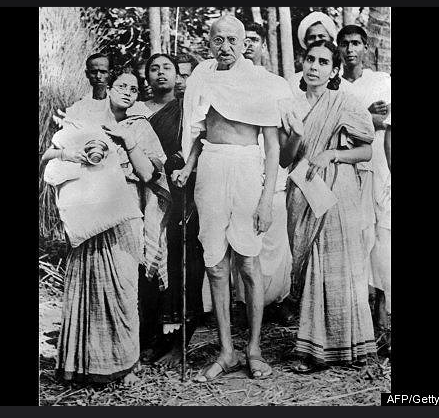

*All pictures (except title photo) from pixabay.com and no credit is needed.

*Title photo (1st photo) from flickr at this link:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/saktishree/9513686123/in/photolist-fuG8r6-qqi83X-7DjvPk-qqkmuk-7Dohu5-7Djwvx-7LdfZa-7Djs2g-aDcVmC-7DjwMr-2RdLSt-7Dogw5-r2Kr9F-fuWKmm-33MSsz-7DjroV-7DoihG-72eLBb-7DjvzB-q3CyiQ-7Djwfa-7DofnC-7DjvbV-7DoirJ-7Djtxr-4n8K4v-qGK14e-i5qEux-6qRxfq-7Djsxg-afm2Aq-7sG8pk-5uQbfq-6qRxEd-862QT1-tDvBVA-7DojJU-7DjucT-2FTQDw-3pCnkZ-7Doj3y-7mSuAi-4jBSQK-8Wnny3-4jmgDt-945vp9-xTHQk-7DohGh-7DjunV-m1WGz

Posted by Saktishree DM.

License allows commercial use if photo was not changed, which it was not.

This was my writing piece from college. A good thesis, but was not seen back in the day when Steem was quite young!

Thanks for finishing the series, this 4th one was the best.

Do you believe that Dutt's criticisms of Gandhi's tactics are legitimate, or do they just reflect a Marxist worldview?

I disagree very much with his criticisms. Although I cannot ever know for sure what Gandhi’s full mission was, he was altruistic. That by itself makes Dutts theory void.

Thanks again for reading!