The Rhythm of "Other-ness" - Written Nov. 9, 2016, detailing my experience with racism growing up in Small Town, VA

I was born in Warrenton, Virginia, on January 13, 1975. On my birth certificate from Fauquier Co. Hospital, my race is listed as “Negro.” My family moved 30 miles away to the small town of Front Royal, when I was about the age of 2. Our first home was a townhouse along Viscose Avenue. Looking back, it was relatively mixed racially with a couple of other Black families in the neighborhood. We were only there for a couple of years and amazingly I still have several memories of making friends, playing a lot, learning to cross the street, rolling down the hill and the rat who ate my Halloween cookies. Great memories from 2 to 4.

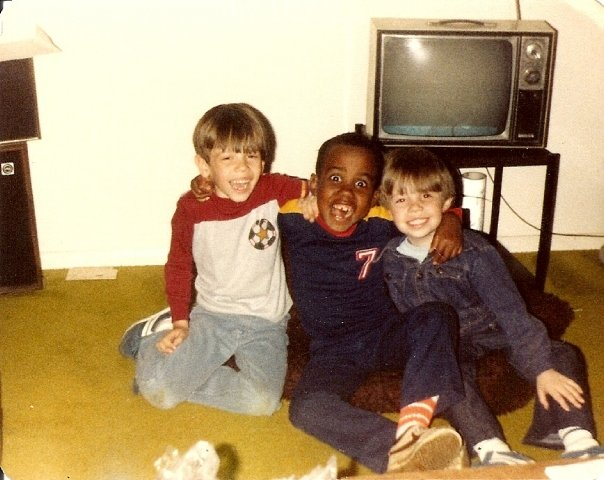

Then we moved across town to a section called “The Royal Village” which was predominantly a working-class, white community, but there was a small contingent of black families on our street. The kids I socialized with the earliest were the kids of these working-class, white families. We played hard and we played a lot. There are many on my friends list who can testify -- hide-and-seek, tag, baseball, football, basketball, kickball, dodgeball/kill ball. You name it. Great times.

However, my parents often recall with a laugh when we first moved to the neighborhood, one day I was outdoors playing with a few of my newly found white friends. My parents had to be somewhere, so they called me in. As I was leaving, I was waving goodbye to my friends who were then waving back, “Bye, nigger.” It didn’t phase me. I couldn’t have been anymore than 4, and I don’t remember it.

Prior to this my parents had raised me nonviolent. I was to never fight, so when ages 5 and 6 came I found myself getting beat up in scuffles, because I always took my parents’ instructions way too literally. My mother had to finally tell me one day that it was okay to defend myself. Don’t just take it. And she laid in this little advice, “They have long hair. Use it.” I used to laugh at that, but thinking back it’s sad to me that my mother felt she needed to resign herself to the fact that I was going to have to literally fight starting at such a young age. By this point, the “N-word” had started to find its way into my white friends’ mouths almost anytime a disagreement occurred, whether it was kickball or hide-and-seek. I wasn’t a good fighter. Often fights just felt even, if anything. Around 6 is when I made friends with my still best-friend, Cory, the other black kid across the street from our home. He was a little older and could fight, so he became somewhat a guardian.

During my childhood, I can remember times going to what-was-then the A&P in Front Royal and white men driving by in trucks, shouting “Niggers!” at my family. White men in trucks shouting the “N-Word” became a theme almost. It was an extremely cowardly act that maybe played into why prefer small cars to this day.

By the age of 10, I had grown weary of physically fighting. It only ever happened in my neighborhood. Never, EVER at school. School is where I found a relative relief. I learned in first grade that I could excel and that set my path in stone. Most of the kids in my classes were white but from varying economic backgrounds. The kids from the middle class did not see what when I returned home from school, and as a kid you don’t think to really share.

I don’t want to give the impression that this was an everyday occurrence. There were many days where I could just be another kid from the neighborhood playing, but by the time I was embedded in school culture, the feeling of being an “other” had already been well-established. There was a neighborhood kid who would tell me sometimes as a compliment, “You’re not black. You’re white.” And I’d take it as a compliment. Then his older brother would call me the “N-word,” and it was back to the drawing board.

I distinctly remember telling kids on the bus one day, as we passed my house and my light-skinned parents were outside, that they were white. I had a shame about being black very early in life. I thought the only beautiful black women were Diana Ross and Donna Summer. I don’t think I ever shared this, but it’s what I carried inside.

So 5th grade, one day I’m on the bus in the back sitting next to one of my white friends who used to live in my neighborhood but had since moved to another part of town. There was a very small contingent -- maybe 5-7 other black kids on the bus-- and an argument ensued between one and a working-class white boy on the bus. Out of that arose a chant among the working class white kids:

“Fight! Fight!

Nigger on white.

If the whites don’t win

Then we all jump in!”

I look for consolation in my friend next to me, but I turn to him and see he’s chanting along with the others. I guess he could feel me staring, so he turned to me and said, “I don’t mean you,” then resumed the chant.

Some of my middle-class white friends were sitting toward the front, looking horrified. Some even later offered consolation.

At a different time, in English class, I remember we had a substitute one day -- a towering, older white man. The only other black kid in this class was a girl who was often very quiet. There was a discussion going on, and in trying to get her attention -- while forgetting her name -- referred to her as “colored girl.” It didn’t hit as hard as the “n-word,” but I do remember thinking, “Man, this is some bull!”

In 6th grade, in English class we read a story that dealt with race which felt extremely awkward because again I was the only black kid in the class. The teacher in an attempt to -- I don’t know -- zeroed in on me and asked, “How does it feel to be called ‘nigger?’” She didn’t know me. She just assumed. I gave the earnest answer of how awful it feels, but wanted to honestly crawl under my desk.

7th grade, I had the luxury of walking to school. The middle school was right around the corner, but even on that short walk. . .

There was the ruddy-faced older kid on the bicycle who rode by and called me “Nigger!”

There were the two white men who drove by in a truck (THEME!) and shouted “Hey Nigger!”

(One of those men later changed my tire at an auto shop in Front Royal. He didn’t remember me, but I could never forget his face. I just stood there and watched him service my car.)

8th grade, while with a group of my closest white friends on the way to the mall. One of the friends had an older brother who was driving us. We handed him a hip-hop cassette to play in which he responded, “Is this nigger music?”

Awkward!

For consolation, after looking in his rearview and making eye contact he said, “I forgot there was one here.”

A culmination of these experiences led to what I finally chose to be during my senior year. The hair, the medallions, the Malcolm X obsession was over-the-top but it was a way for me to embrace the otherness, as I’d finally realized that I could not bury or hide it. I had to own it.

I share these personal experience, not as an indictment on the parties involved but as a warning of sorts. These are the things that happen in a society where you isolate, ignore and create “other-ness.” Awareness! Awareness! Awareness!

I cannot celebrate a Trump victory, because he established himself as an isolationist. That made him extremely popular, and it made me remember my childhood. Because I know what it is to be embedded with the feeling of being an “other,” I choose to respect, listen and work to not do that to other groups. I am not an ally. I am family. Physical walls are only an extension of our inner walls, so miss me with the “Build a wall” rhetoric, son.

I am not hopeless at all. The sky isn’t falling, although the markets are a little bouncy. The work that we’ve already been doing just continues. Give room to listen to the stories of others, especially if you get the chance off social media to do it.

Please continue to live, love and laugh hard. . . and forgive my typos.