IN DEFENSE OF: BENEFIT (JETHRO TULL - 1970)

It was probably November of 1995 (if memory serves) when father bought us our first personal computer. It was a Pentium 120 with 32 Mb of RAM and Windows 95 preinstalled (at that time it was a flagship). He bought it alongside two games of MY choice: Doom and FIFA 96, two of the most successful games of their period. I was 9 years old at that time and “excited” would be an understatement of what I felt at that moment.

There was just one thing that kept me from enjoying my games at the fullest: the sound card was BROKEN and there was no way to have it properly fixed (it was a Sound Blaster 32 card, one of the best in the market). So in the meantime, we had to live with background music to make up for the lack of sound and immersion.

It was a time when you needed to be basically a self-taught computer engineer in order to play any PC game, so you had to memorize the ports and IRQ to correctly configure the card. (sigh) Those were the days!

All in all, it was a very nice and optimized gadget overall, even though it was a clone PC (and, as far as I could tell, clone PCs were known as budget-friendly alternatives to brand PCs at the cost of optimization).

Well, I hope you enjoyed this PC review of…. OH WAIT! What the heck was I actually reviewing? LOL just kidding! I promise this little personal anecdote has a goal in the midst of all this, and you’ll realize that as you keep reading below.

As I was saying, we had a PC with no sound, so background music was a temporal solution (that was, until we bought a new PC, unfortunately). In the meantime, we used to listen to lots of oldies (Doors, Beatles, Zeppelin, Dire Straits, etc.) or, occasionally, some 80’s metal music courtesy of my older brother. We still had our father’s old record player and the album library was PACKED! (He was a musician after all), so we had lots of music to keep us aroused.

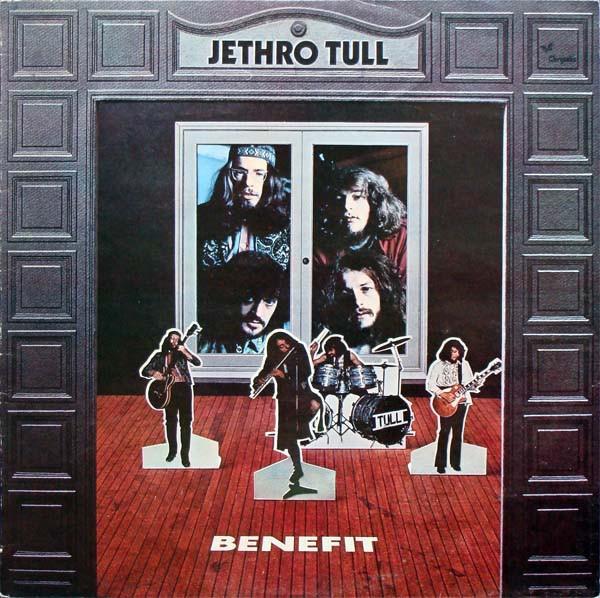

Anyways, one day, my older brother decided to put to the turntable an album from this band I never heard about. It was recommended by one of his buddies so he was giving it a go. As the needle was starting to “scratch” the vinyl to produce the first fluttering flute notes of the first track, I proverbially jumped out of my seat in awe, thinking: JAZZY FLUTE! What the Dickens!? In a ROCK album!? (And keep in mind that I had already listened to bands like Led Zeppelin, which employed many exotic and out-of-place instrumentation in many of their songs). I gazed onto the four-headed monstrosity on the album cover (just kidding, they were just the heads of the band members behind a window), and above I read the words “JETHRO TULL”, so I was left at that moment thinking “this Jethro guy could surely play a flute”. It then was informed to me that it was the name of some farmer in the XVIII century and the name was chosen for no particular nor otherworldly reason by a history enthusiast of the booking agents’ staff. But anyway, I digress.

Moving on. My 9-year-old mind could not had coped with the fact that this type of music existed in this side of the known universe. And keep in mind that 25 years had already passed since the album was first released, so the hype was very much over at that point. But the fact remained that, after everything was already “said and done”, it still captivates many people to this day.

There’s just one caveat: this is hardly considered a “Prog” album by most progressive rock fanatics’ standards. In fact, this album didn’t exactly revolutionized the musical world, nor was it received with much praise even, compared to its predecessors or its successors. At that point in time, Woodstock had already established its “civilization of love and peace” after Nam, King Crimson would release THE quintessential progressive rock album (although many other acts would claim that feat since 1967), the Beatles were as good as dead and the moog synthesizer was in virtually every pop-rock album since 1968 at least, so Jethro Tull at this point hardly stood out in all this convolution. So why did it captivate me so much? This question could not admittedly be answered properly without rose-tinted glasses on. But are reviews always objective fact-stating activities? Hardly! This was the first time I listened to this kind of music, so naturally the shock factor that this album produced in me could hardly be replicated.

But more to the point. Many professional reviewers would give an album two or three listens in order to give an album a “fair” rating. But only when you’ve listened to an album dozens of times you begin to wonder what those reviewers might had missed from their listening experience. In my case, as a child with nothing better to do than study, play and listen to music, I would compulsively pull out this one LP from its sleeve and delve into every note produced in order to catch its subtleties. I believe that, to this day, this is my most played rock album ever, so who would be more qualified to review it than yours truly?

Following that train of thought, many music critics and reviewers dismiss this album as “inconsistent”, “dull”, “dreary”, and so on. For one thing, I disagree with the “inconsistent” tag. Why? The word “inconsistent” means that something doesn’t fit with a whole, or that something doesn’t remain the same throughout. However, these reviewers tend to throw this word out very liberally to simply mean that something is not “catchy” or “memorable” enough (and other highly subjective and ambiguous terms). In the case of this one album, in my humble opinion, there’s nothing in it to suggest a lack of consistency. In fact, out of all Jethro Tull albums to date, this one is their most consistent and tightly produced. If I wanted to point to an inconsistent album in their repertoire that would be Minstrel in the Gallery (which doesn’t appear to be the same album when flipped from one side to the other). Whereas in this album there is a mood that is uniformly spread throughout (ironically, these reviewers state that the album is “inconsistent” while at the same time “maintaining the same dreary and pessimistic tone throughout”, highly contradictory statements if you ask me).

As a matter of fact, there are some very lighthearted moments on this album, contributing to what I consider excellent pacing. Songs like “Inside”, “Teacher” (depending on which version you own) and even the slower but not less merry “For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me” are very good examples of cheerful ditties that kind of balance out the sorrowfulness of the rest of the album.

Yet, it’s hard to disagree that it was not the Jethro Tull of the previous two years, mainly due to their shift from the delta blues style to a more British rock style if there ever was one (by the way, blues mean “sadness” and “melancholy”, go figure). This album definitely feels British to me, in contrast to the American flavor of their younger days. , I dare you to listen to “To Cry You A Song” not imagining yourself “walking through London town”, also helped by the fact that Ian is singing with his natural voice (either that or he bit his tongue before recording) so his Edinburgh accent is really apparent (or should I simply say British, since obviously Londoners and Edinburghers don’t speak alike). All in all, it is more emotionally drenched than “Stand Up” but at least it sounds sincere without being overly preachy (like Aqualung would end up being, but we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it).

One special mention has to be done to Glenn Cornick, whose contribution to the overall sound of the album is difficult to dismiss, especially with his walking bass playing in “To Cry You A Song”, which is definitely an added value to an already great tune. Unfortunately, he would not remain with the band for the next album (for whatever drug-related or Ian-Anderson-being-a-jerk reason) and instead we got one Hammond-Hammond (who is, in my humble opinion, far less competent) for the remainder of this iteration.

In that vein, one thing that gained my attention as I was revisiting the album was how tight and well-structured the instrumentation was. For example, in songs like “Nothing to Say”, basically every instrument contributed to form a cohesive harmonic layering, as shown in the chorus between the lead guitar of Martin Barre playing an ascending scale and the other instruments playing in oscillation until the climax, as if it were a brass arrangement of sorts. More surprising is the fact that perhaps it was not originally intended to be that way and it just happened, it just clicked. Not many rock acts can boast of being able to come up with these subtle complexities in their arrangements and doing it so naturally and rather unintendedly (many employ complexity but hardly excel in subtlety). Another song that comes to mind doing this is not from this album, but was equally terrific: the Aqualung outtake “Wond’ring Again” (which also, curiously, had Glenn Cornick on bass), in which the lead guitar appears playing a second voice accompanying the main melody and complementing the piano and acoustic guitar.

Then there were the double-tracked guitar solos in “To Cry You A Song” and “A Time for Everything”, which were to my taste more hit than miss. Even though they were not flawless, at some point I could not make out which guitar was in which track, leading me at some point to believe that the same guitar was playing a specific phrase or lick when in fact it was the product of merging the two tracks. I thought that was a very interesting touch that also stood as an added value. This could be attributed more to studio mixing skills than guitar playing skills, but Martin Barre’s competency is not to be underestimated (I say that as a guitar player myself).

I could also point out that I always had a soft spot for “Alive and Well and Living In” and, yes, I realize that basically it is the most dreaded song by critics (but I’m not like most critics, so sue me). John Evan’s Guaraldi-esque piano playing in this track was simply delightful, and really makes the band sound more professional and clever than many of its contemporaries.

Other songs worth mentioning are: the critically acclaimed “With You There to Help Me”, which was the band’s first song to have weird reverse tape effects (which in this case worked to the tune’s favor) and it’s basically a framework for Ian’s flute skill showcasing, though it’s a very good framework. “Son”, which is by far the hardest sounding tune of this album and basically juxtaposed between two of the softest songs, creating a perfect balance in mood. “For Michael Collins, Jeffrey and Me” which finds Ian’s singing at its most sincere and melancholic, perhaps because it regards his all-time best friend (the aforementioned Cornick’s replacement) and a great member of the Apolo 11 crew that landed on the moon one year before (all this time I thought that he meant the Irish independence advocate). “Teacher” (appearing in the UK release, I believe) was, in my opinion, the most overrated song on the album, and it was basically “Tops of the Pops” material (it was released as a single, after all), but it was lauded even by die-hard Tull fans. I, for one, could never get into it, even though I loved the interlude with Ian’s jazzy flute and Cornick’s running bass notes (as a sidenote, I'm not against pop music and have a knack for many pop bands, but I found this particular song to be a bland and deliberate attempt at appealing to a broader audience). “Inside” was very sappy but memorable, and a nice comic relief (although not really comic but rather reflexive) to an overall somber album. “Play In Time” is another track I could frankly live without, it was somehow supposed to be a homage to the Jethro Tull of old, but, though not necessarily a filler, it came with a twist (tape effects) which honestly made the song age very badly. And, lastly, there’s “Sossity, You’re A Woman”, which was supposed to be a statement on God-knows-what and society unwilling to accept change (or something like that), ended up being my favorite song in my early years, and It is still up there as one of my favorite songs, basically because I loved its haunting Elizabethan-styled acoustic vibe.

With all of the above said, my general statement about this album is as follows: many would wait for the release of “Aqualung” to find out what direction the band would undertake, but for me, this was the real turning point in the band’s change of direction. “Aqualung” admittedly had more catch, but this album had a sophistication and a personality of its own and, in many ways, was more uniform and tight in its overall presentation. This was a band in the year 1970 trying to find its own sound, and, in my opinion, they let the pendulum swing too far by the end of 1973. This, to me, was the sweet spot, right at the beginning, when the pomp was still hidden, that is, until Ian decided that it was time to get more “ambitious” and “otherworldly”. Now, don’t get me wrong, I still enjoy their other 70’s albums (and find their late-70’s folk rock offerings to be quite enjoyable), but this album, amidst all the flaws and the primitive production quality, is one of the most forgotten and underrated gems in this band’s extensive catalog. It’s not a masterpiece, but yet it manages to have a spot in my top 5 favorite Jethro Tull albums list (even above Aqualung).

ROSE-TINTED GLASSES OFF

#PROGROCK #JETHROTULL #MusicInspiresLife

Congratulations @chusbreak! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Congratulations @chusbreak! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!