Grading America’s ‘scientist-in-chief’

Barack Obama sought to map the brain, cool the climate and chart a path to Mars. As he prepares to leave office, let's look back at the scientific highs and lows of his presidency.

Betting Big on Biomedical Science

When president-elect Barack Obama chose physicist John Holdren as his top science adviser in December 2008, some biomedical researchers worried that the pick signalled a White House bias towards physical science.

Obama quickly put those fears to rest. Within weeks of his inauguration, he had overturned restrictions on research using embryonic stem cells. He has gone on to launch major initiatives to map the brain, develop personalized medical treatments and cure cancer.

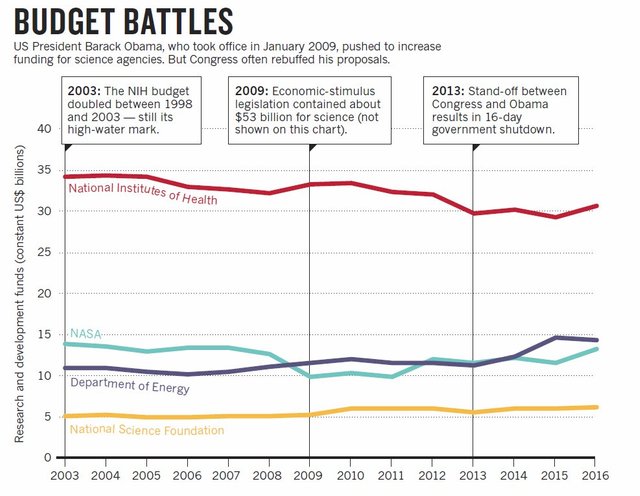

But faced with a penny-pinching Congress, Obama’s strong support for biomedical science has not translated into significant funding gains for the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). The agency has seen the purchasing power of flat research budgets eroded by inflation. “The life sciences were a significant priority for the Obama administration,” says Gregory Petsko, a biochemist at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. “But with Congress being the way that it is, there was a limit to what Obama could do as far as increasing support of biomedical research.”

It is the big initiatives that will probably form Obama’s lasting biomedical legacy, says Benjamin Corb, head of public affairs at the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in Rockville, Maryland. In 2013, Obama announced the Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) initiative to map the human brain. In 2015, he unveiled the Precision Medicine Initiative, which includes an ambitious study of health records and genomic information from one million people in the United States. And in January, he introduced the Cancer Moonshot, a US$1-billion proposal to double the pace of cancer research in five years.

NIH director Francis Collins, who led the Human Genome Project in the 1990s, likens Obama to a player who scores three goals in the same game: “I said to him, basically, ‘Mr President, you have achieved a hat-trick.’”

But such programmes may come at a cost to basic research funding, even as they draw attention to areas of science that may be overlooked or underfunded.

And it’s not clear whether Obama’s major initiatives will survive under the next president. Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has said that she would continue the Cancer Moonshot initiative. She also supports Alzheimer’s disease research, which bodes well for the BRAIN initiative if she is elected. Republican candidate Donald Trump has no clear policy on biomedical research.

But the next president won’t be making that decision alone. Patient advocates drive major changes in biomedical research priorities and funding over time, and will probably ensure that Obama’s big-science initiatives continue, says Mary Woolley, president of the science-advocacy organization Research!America in Arlington, Virginia. “Determined advocates are not going to take ‘no’ for an answer,” she says. “They’ll be the ones that bridge administrations.”

Space Race Stalls

Obama tried to shake up the US space programme, including NASA’s long-standing plan to send people to Mars. But nearly eight years — and a series of U-turns — later, he has little to show for his effort.

“Where NASA is today is really not all that different from where it was during the last presidential transition,” says Marcia Smith, a space-policy analyst in Arlington, Virginia, who runs SpacePolicyOnline.com.

A crewed Mars mission remains two decades away. Its schedule is constrained by the funding available to develop the necessary hardware — a new heavy-lift rocket and crew capsule to sustain astronauts in deep space. That is almost exactly the situation NASA was in eight years ago, bar one detail: Obama ditched the Moon as a first stop for astronauts on their way to Mars.

That decision, in February 2010, stunned NASA, Congress and space-policy experts. Obama cancelled the Constellation programme, which his predecessor George W. Bush created to send US astronauts back to the Moon in preparation for an eventual Mars trip. Two months later Obama announced a different course: astronauts would visit a yet-to-be-chosen asteroid before heading off to the red planet. The White House did not consult Congress on the switch, angering powerful members who represent space-industry employees in states such as Florida, Texas and California. “The hostility created by the way the Obama administration rolled that out still lingers in Congress,” says Smith.

The decision also alienated traditional US space partners such as Europe and Japan. Little to no weight was given to the international implications of the decision to abandon efforts to lead an international return of humans to the lunar surface.

NASA was forced to modify its Mars plan in 2013, when it became clear that it did not have the technology to support astronauts in deep space. The White House introduced a controversial stopgap measure: instead of a crewed mission to visit an asteroid, a robot would drag an asteroid near the Moon where astronauts could then visit it.

Asteroid scientists have roundly denounced the plan, but it is moving forward despite slipping schedules and ballooning costs. The hardware for crewed deep-space journeys is also at risk of schedule and budget delays. The heavy-lift rocket is scheduled for its first test flight in November 2018, while the crew capsule’s is set for August 2021.

Obama extended US participation in the International Space Station for four more years, to 2024 — a move generally acclaimed by scientists. And he oversaw the shutdown of the space-shuttle programme, a process begun by Bush. After the last shuttle, Atlantis, flew in July 2011, the United States turned to Russia to buy rides to orbit for its astronauts.

NASA is relying on commercial companies to fly equipment and — eventually — astronauts to the space station. The first commercial cargo flights began in 2012, and the first astronauts are scheduled to fly aboard commercial spaceships no earlier than 2017.

Scientists grumble about the relative lack of flagship missions in development. One of the biggest, a proposed mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa, has been pushed through not by the White House or NASA, but by a Republican congressman from Texas who is enamoured with the idea of life on icy worlds.

Uneven Progress on Scientific Integrity

Many researchers who watched Obama’s inauguration in 2009 were thrilled by his pledge to “restore science to its rightful place”. But scientists and legal scholars say that, in many ways, Obama has failed to live up to that lofty promise.

In general, government researchers have enjoyed more freedom — and endured less political meddling — than they did under the previous president, George W. Bush. Bush’s administration was accused of muzzling or ignoring scientists on subjects ranging from stem cells to climate change.

In March 2009, Obama instructed agencies to develop policies to reduce political interference and increase transparency about the research used in policy decisions. And when the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) surveyed federal researchers in 2015, most said that their agency adhered to its scientific-integrity policy.

But critics say that Obama’s White House has not shied away from exerting political influence over science. In 2011, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sent a proposal to the White House that would strengthen controls on ozone pollution, based on guidance from its scientific advisers. But Obama directed the agency to withdraw the plan, citing the cost of the stricter limits at a time when the economy was still recovering from a recession.

And that same year, Health and Human Services secretary Kathleen Sebelius overruled the Food and Drug Administration’s finding that the emergency contraceptive ‘Plan B One-Step’ was safe to dispense over the counter for all women and girls.

In both cases, science eventually won out: the EPA approved stronger ozone standards in 2015, and the FDA approved unrestricted sales of Plan B in 2013 after judges ruled against the agency. Nevertheless, these examples show how political considerations have sometimes trumped scientific ones during Obama’s tenure, says Lisa Heinzerling, a law professor at Georgetown University in Washington DC.

“There are structures in place that threaten scientific integrity and encourage the injection of politics into matters that are supposed to be scientific or technical,” says Heinzerling, who worked at the EPA for two years under Obama.

Science advocates are concerned about how political influence shapes science behind closed doors at the White House. The president’s Office of Management and Budget, which reviews proposals for new rules and regulations, can make substantial changes or kill a policy without explaining why.

The recent UCS survey revealed room for improvement at several agencies. Nearly half the scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that their agency gave too much weight to political interests; that proportion rose to 73% at the Fish and Wildlife Service. And less than 60% of scientists at the four agencies surveyed said they could openly express concerns about the work of their employer without fear of retaliation.

Climate Policy Hots Up

Global warming was one of Obama’s top priorities — and one of the most difficult to address, given strong opposition from Republicans in Congress. Yet he managed to help broker a global climate accord and push through regulations to curb greenhouse-gas emissions from cars, trucks and power plants.

The president’s earliest actions capitalized on the global financial crisis. In February 2009, Obama signed economic-stimulus legislation that included nearly $37 billion for clean-energy research and development (R&D) at the Department of Energy. Four months later, with failing car companies seeking a federal bailout, the Obama administration proposed higher fuel-efficiency requirements and the first greenhouse-gas standards for passenger vehicles. The regulations, which took effect in 2012, will nearly double the average fuel efficiency of vehicles by 2025, to around 23 kilometres per litre.

And after his campaign for a comprehensive climate bill failed in 2010, an emboldened Obama used existing laws to issue regulations that curbed greenhouse-gas emissions, bolstered energy-efficiency standards and expanded energy R&D programmes.

But the president’s big push on climate came in advance of the United Nations climate summit in Paris in 2015. He committed the United States to reduce emissions by at least 26% below 2005 levels by 2025, and negotiated directly with countries such as China to build support for a global climate agreement. The final version, adopted on 12 December, aims to hold average global temperatures to 1.5–2°C above pre-industrial levels.

“Paris is a major achievement for the world,” says Robert Socolow, a climate scientist at Princeton University in New Jersey. “I don’t think it would have happened without Obama.”

Yet Obama’s domestic achievements could be undone by legal challenges. In February, the US Supreme Court temporarily blocked a federal regulation to reduce emissions from existing power plants. The fate of that rule— the cornerstone of Obama’s plan to reduce emissions — could depend on the election in November. The Supreme Court is down one member and the next president will choose a replacement, who could decide whether the climate rule stands.

Some environmental experts say that Obama should have pushed harder for a comprehensive climate bill, rather than settling for piecemeal regulations. “All of these things are actually small bites at the apple that won’t achieve meaningful emissions reductions over time,” says Catrina Rorke, director of energy policy at the R Street Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington DC.

Others criticize Obama for encouraging a vast expansion of domestic oil and gas development, even as he sought to wean the country off coal and curb its greenhouse-gas emissions. “The administration is still trying to have it both ways,” says Stephen Kretzmann, executive director of Oil Change International, an advocacy group in Washington DC.

Obama rejected the Keystone XL pipeline, which would have carried oil from the Canadian tar sands to US refineries, and has said that some fossil fuels should be kept “in the ground”. But his administration continues to push an ‘all-of-the-above’ energy strategy that leads to higher production of domestic fossil fuels, Kretzmann says.