Arête

In Plato’s Apology, Socrates draws a comparison between himself and Achilles, the great hero of the Trojan War. He explains that his actions are compelled by morality - by what is right - despite knowing that they will ultimately bring his own death. He claims to be following the example set by Achilles, whose decision to fight and die was spurred by his own conception of what is right, and how a man should live. Both men were driven by the concept of arête, which means excellence or virtue; the concept of living up to one’s full and highest potential. Socrates made this famous analogy because it succinctly highlighted his point, and because Achilles’ tale was so widely known. Did Socrates indeed model himself after Achilles, or are his words merely a comparison of convenience? To see if the analogy can be extended further will require a closer examination of ancient Hellenic conceptions of arête, civic duty, and hubris in relation to the lives of these two seminal icons of Western Civilization.

Death of Socrates, Jacques Louis David.

To the heroes of Homer’s Iliad, the pursuit of individual excellence was a driving factor. Achieving a lasting fame by individual accomplishment was crucial to leading a good life, and provided a sense of purpose to the mythical Achaeans. The ideals of arête, as set down by Homer and the epic poets, would blossom into a sacred principle for the classical Greek world to come, and no less for Socrates himself. For Socrates, however the principles of individual excellence had matured into something far removed from the primitive arête pursued by Achilles and his cohorts. For the ancient heroes, greatness consists in besting other men, be it comrades in sport, or enemies on the battlefield. However, this greatness was not exactly based on personal achievement; a man was great because it was the will of the gods. A man who won a horse race or single combat on his own merit was not as great as the man who won because the gods intervened on his behalf. Achilles followed his path not because he wanted to, or because he thought it was the right thing to do, but because such was the will of the gods. His rewards were possessions, prestige, and even eternal fame, yet these things ultimately gain him nothing, as his shade laments in the underworld.

Arête, sometimes personified as a goddess, Sarah Ferguson. flickr

For Socrates, arête was a far “higher,” more refined concept. It meant being the best you can be, at all times and in all doings. Socrates held himself up to a standard of excellence that spanned his entire life. Excellence had to begin and end with the individual, and not just in the realm of physical feats. Living a good life meant subjecting all beliefs and actions to the analysis of reason and intellect. He sought to remove myth and and superstition from daily life, not to honor and live by them, as did his mythic forebears. Living a life in this way was the ultimate reward for Socrates, for he believed that prestige, fame, and wealth were meaningless and empty without personal integrity. This attitude allowed him to live and die like a man, without fear or regrets. The example he set is a far cry from the petty, childish manner in which Achilles behaves all throughout the Iliad.

Achilles’ priority is Achilles; the Argive community, even his close friends, rate a distant second. His original refusal to fight is brought about by the taking of his prize, the slave-girl Biseis. Achilles is reminiscent of a schoolchild sulking because of some minor slight. Instead of behaving like the greatest warrior of the ancient world, he cares only about getting back at Agamemnon, and gives no care to the slaughter his own comrades are receiving without his help. He welcomes the carnage inflicted upon his fellow Greek, for it shows how indispensable he is. He even allows his best friend, Patroclus, to fight (and die) in his place rather than swallow his pride. For Achilles, the demands of society and community are completely subsumed by his individual desires.

Achilles.

Socrates, on the other hand, seems dedicated to the greater good. He saw that the city-state was in great danger of being destroyed by the pettiness and greed of its citizens, and reasoned that only a shift in the Athenian mind, toward reason and righteousness, could bring the polis back from the brink of ruinous war and squabbling. Though many saw him as antagonistic to the democratic ideals of the state, he saw himself as a defender of the Laws, people, and spirit of Athens. By refusing to escape from his execution, he proved that he valued the Laws - the ties that bound the community together - over his own personal desires.

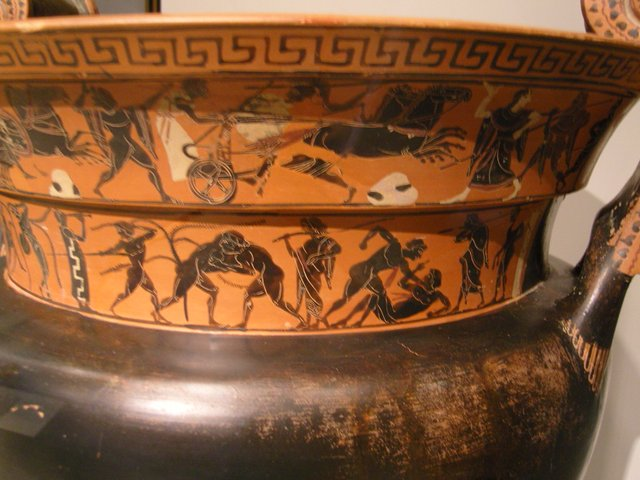

Greek battle scene.

To the ancient Greeks, hubris was not just overweening pride or arrogance, as it has come to mean in modern parlance. Hubris involved actions which brought shame and humiliation on a victim. This ancient conception of hubris was defined by Achilles treatment of Hector’s corpse, as well as by his sacrifice of Trojan prisoners of war during Patroclus’ funerary games. By these actions, Achilles not only displayed his dominance, but also his sense of pride and superiority. His pride was suffused with contempt for human life and human customs, as well as higher moral precepts. Socrates too, was not known for his humility, and was thought by many to be quite arrogant. While it would be difficult to deny that Socrates defeated his foes with rhetorical relish, it seems to me that he drew his ultimate pride in his dedication to his ideals. It is true that Socrates’ infuriating dialectics did indeed bring humiliation upon his opponents, but I believe even this sprung from his motives to help his fellow Athenians see the errors of their thinking. In this way they could the grow, mentally and spiritually, and attain “the good life” that Socrates saw was a man’s birthright. It can be argued that Socrates displayed great hubris by refusing to sensibly defend himself at his trial, and then subsequently refusing to escape from his death sentence. Indeed such actions brought about violence, if only to himself. Yet while he was certainly thinking of himself, I believe he ultimately chose such a course out of a selfless sense of duty; to Athens, to her people and her Laws, to Greek ideals, and ultimately, to humankind.

Achilles proved that luck and fortune may make a man renowned, but Socrates showed that reason and integrity can make a man truly great. While the epic poems of Homer may have been the seed of Western Civilizations, it was the example laid down by Socrates that birthed it into the world. Both men set potent examples for the generations of westerners to come, but it is from the lessons of Socrates that the highest standards of the West have been forged. Achilles showed that men may put themselves before their tribe, but Socrates showed that such personal greatness must be channeled back into the greater good, or it will always be shallow and meaningless, as hollow as the shade of Achilles, muttering in the oblivion of mindless death.

I enjoyed reading this

History is great!

Socrates and Plato were indeed some fantastic thinkers. I think it is too bad that so many people don't dig deeper into what they were trying to get across. This was a really great post. It would be interesting to see how some of the thinkers of our age would stack up against them given the chance.