Who Were the Philistines?

If the Deuteronomistic History of the Bible is to be believed, the Philistines were the implacable enemies of Israel for much of their history—especially the period from the Judgeship of Samson to the rise of the Divided Monarchy. They played a much smaller rôle in the later history of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Who were these Philistines? In which period of history did they flourish? These are the questions we will be trying to answer in this article.

Biblical Origins

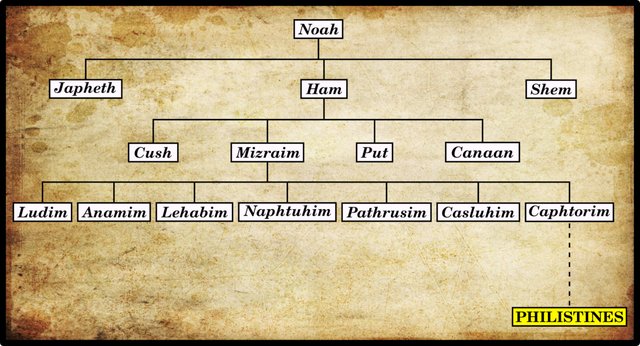

The Philistines are introduced to us in the tenth chapter of Genesis, where they are listed among the descendants of Noah’s son Ham:

Now these are the generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth: and unto them were sons born after the flood ... And the sons of Ham; Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan ... And Mizraim begat Ludim, and Anamim, and Lehabim, and Naphtuhim, And Pathrusim, and Casluhim, (out of whom came Philistim,) and Caphtorim. (Genesis 10:1-14)

The names ending in -im are plural nouns in Ancient Hebrew, and are generally used to designate various nations and their lands. Most of the names in this list are thought to refer to various tribes or nations who dwelt in North Africa or the adjoining part of Asia. Ludim way be a scribal error for Lubim, who are mentioned in II Chronicles 12:3, 16:8 and Nahum 3:9. In Hebrew ב [b] and ד [d] are easy to confuse (Macalister 4).

| Hebrew Name | Nation |

|---|---|

| Mizraim | Egyptians |

| Ludim | Libyans? |

| Anamim | Unknown |

| Lehabim | Libyans? |

| Naphtuhim | Napata in Kush? |

| Pathrusim | Pathros (Upper Egypt) |

| Casluhim | Unknown |

| Philistim | Philistines |

| Caphtorim | Cretans, Cypriots |

The parenthetical remark—that the Philistines came out of Casluhim—is probably a marginal gloss that was later incorporated into the main text (Macalister 5). Archibald Sayce and Macalister believed that it was misplaced and ought to follow Caphtorim, as in the image above:

The reference to the Philistines has been misplaced. Other passages in the Old Testament make it clear that their original home was among the Caphtorim and not among the Casluhim. (Sayce 136 : Macalister 5)

As Sayce points out, this seems to be confirmed by a passage in Jeremiah:

... for the Lord will spoil the Philistines, the remnant of the country of Caphtor. (Jeremiah 47:4)

Macalister notes that the Hebrew word that is translated here as country, אִ֥י (’î), is rendered in the Revised Version ‛island’, with marginal rendering ‛sea coast’ (Macalister 5).

Another prophet, Amos, also speaks of the Philistines as being from Caphtor:

Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt? and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Syrians from Kir? (Amos 9:7)

In the Book of Joshua, we are told that the Philistines had organized themselves into a confederation of five cities—Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gath & Ekron—by the time Joshua’s Conquest of Canaan was complete:

Now Joshua was old and stricken in years; and the Lord said unto him, Thou art old and stricken in years, and there remaineth yet very much land to be possessed. This is the land that yet remaineth: all the borders of the Philistines, and all Geshuri, From Sihor, which is before Egypt, even unto the borders of Ekron northward, which is counted to the Canaanite: five lords of the Philistines; the Gazathites, and the Ashdothites, the Eshkalonites, the Gittites, and the Ekronites; (Joshua 13:1-3)

But where was their original homeland Caphtor?

Caphtor

The identity of Caphtor is still a matter for scholarly debate. Over the centuries several candidates have been proposed:

- Cyprus

- Crete

- Cilicia

- Somewhere in the Nile Delta (Damietta, near Pelusium?)

- Upper Egypt (Qift, or Coptos?)

- Colchis, on the Black Sea

- Cappadocia, in Anatolia

- Northern Syria

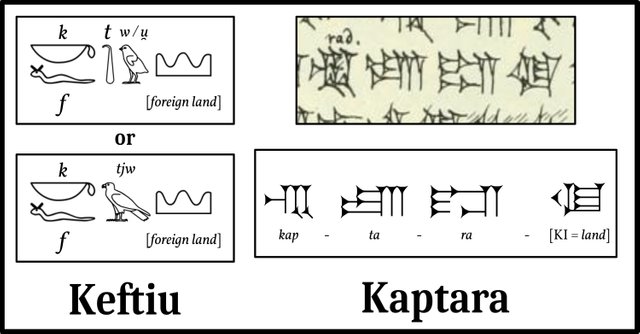

The situation is further confused by the uncertainty of whether various toponyms in ancient sources refer to Caphtor or another place. Egyptian inscriptions mentions two places with similar names:

- Keftiu or Keftu [k-f-tjw or k-f-t-w]

- Kaptar [k-p-t-ȝ-r]

The character yogh, ȝ, is used by Egyptologists to represent the Hieroglyphic alef glyph, the Vulture.

J V Luce, Professor of Classics at Trinity College Dublin, who studied the relevant Egyptian inscriptions for a book on the legend of Atlantis, was satisfied that Keftiu was Minoan Crete.

‛Keftiu’ means either ‛the island of Keft’ or ‛the people of Keft’, depending on what determinative is added to the hieroglyphic. The root ‛keft’ has been connected with caput [Latin for head] and capitul, and it has been pointed out that in the Old Testament ‛kaphtor’ is used for the capital of a pillar [see Strong’s 3730, page 57]. The ancient Egyptians probably regarded remote and mountainous Crete as one of the ‛pillars of heaven’ which supported the sky at the four corners of the world they knew ... Imagine Solon’s reaction when confronted with this sort of information about ancient Keftiu. He could not have failed to associate it with the myth of Atlas, who, according to Homer, had a daughter in a remote western island and kept ‛the pillars which hold the sky about’ [Odyssey 1:48-54]. My suggestion is that Solon translated Keftiu by Atlantis, the island of Atlas ... (Luce 56)

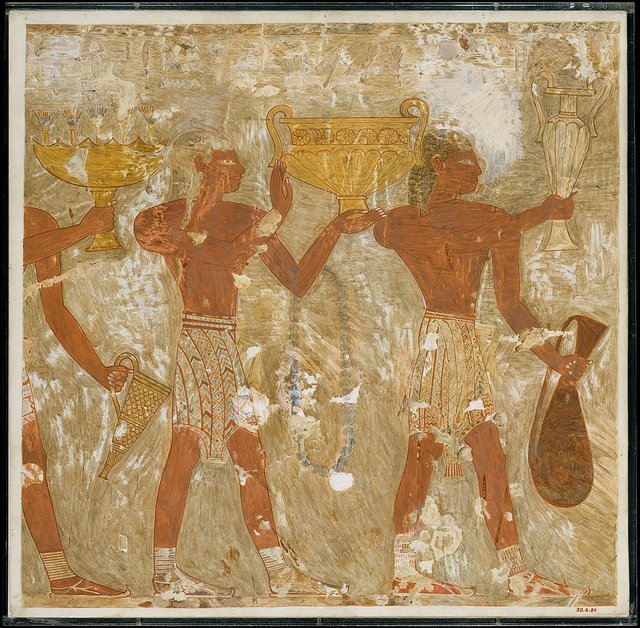

Egyptian references to Keftiu largely disappear in the middle of the 18th Dynasty, during the reign of Amenhotep II (Luce 144, 174). There are fleeting references to it in inscriptions of Amenhotep III and Ramses II, where it appears in lists of tributary nations, but these lists were compiled for propaganda purposes and can not be taken literally (Luce 214 n 27). It was around the time of Amenhotep II that the final collapse of the Minoan Civilization on Crete occurred. The island was subsequently invaded and colonized by Mycenaean Greeks.

The other Egyptian toponym, Kaptar [k-p-t-ȝ-r], occurs only in a list of places inscribed on the temple of Kom Ombo in Upper Egypt. This temple dates from the Ptolemaic Period, so this toponym may simply a transliteration of the Semitic Caphtor.

Cuneiform texts mention a place called Kaptara. In the well-known Sargon Geography, a Babylonian treatise on the geography of Sargon the Great’s Empire, we read of Anaku and Kaptara, the lands across the Upper Sea (Schroeder 68, Line 41 : Albright 196, 236-237). The Upper Sea is the Mediterranean. As anaku is the Akkadian word for tin, this land has been identified with Cyprus, which was an important source of bronze—an alloy of copper and tin—at the time. This leads one to conclude that Kaptara probably refers to Crete, not Cyprus. But this interpretation has had its critics (Albright 236-237).

If the Philistines were descended from the pre-Hellenic inhabitants of Crete, could their name be related to that of the Pelasgians, the indigenous people of the Aegean? This has been a popular theory for almost three centuries:

If we had any clear idea of what the word ‛Philistine’ meant, or to what language it originally belonged, it might throw such definite light upon the beginnings of the Philistine people that further investigation would be unnecessary ... Various conjectures as to the etymology of this name have been put forward from time to time. One of the oldest, that apparently due to Fourmont, connects it with the traditional Greek name Πελασγοί [Pelasgoi] ; an equation which, however, does no more than move the problem of origin one step further back. [Footnote 1: Réflexions critiques sur l’origine, l’histoire et la succession des anciens peuples (1747), ii. 254 (Macalister 1 ... 2)

DNA evidence has recently confirmed the link between the Philistines and the Aegean:

Here, we report genome-wide data from human remains excavated at the ancient seaport of Ashkelon, forming a genetic time series encompassing the Bronze to Iron Age transition ... We find that all three Ashkelon populations derive most of their ancestry from the local Levantine gene pool. The early Iron Age population was distinct in its high genetic affinity to European-derived populations and in the high variation of that affinity, suggesting that a gene flow from a European-related gene pool entered Ashkelon either at the end of the Bronze Age or at the beginning of the Iron Age. Of the available contemporaneous populations, we model the southern European gene pool as the best proxy for this in-coming gene flow. Last, we observe that the excess European affinity of the early Iron Age individuals does not persist in the later Iron Age population, suggesting that it had a limited genetic impact on the long-term population structure of the people in Ashkelon. (Feldman 1)

Today most archaeologists believe that Caphtor-Keftiu-Kaptara refers to Crete, but Cyprus still has its adherents. One such is the historian Emmet Sweeney:

Now Caphtor is usually identified as Crete, so that the Philistines are popularly viewed as a race of Aegean immigrants. However, the great flood of immigration to the Canaanite coastlands during the Palestinian Middle Bronze II (i.e. the Hyksos epoch) comes from Cyprus, and for this reason the present writer identifies the Philistines as Cypriots. Nevertheless, this seafaring race did indeed have close links with the Minoan Cretans, as we shall presently see. (Sweeney 131)

In Cypriot archaeology, the Middle Bronze Age is divided into three phases: the Middle Cypriot I, II and III (Edwards 165). There is considerable evidence of close interaction between Cyprus and both Egypt and the Levant during MC II and III:

During M.C. I there was little or no sign of contact with Egypt or the Levant ... Specific contacts with Syria, Palestine and Egypt start during M.C. II ... What in M.C. II had been a mere trickle of exports to the eastern markets became a flood in M.C. III ... The commitment of Cyprus to the markets of western Asia in the M.C. III period, a commitment which continued into the first phase of the Late Bronze Age, makes all the more remarkable her eventual change of allegiance to the merchants of the Aegean ... (Edwards 174)

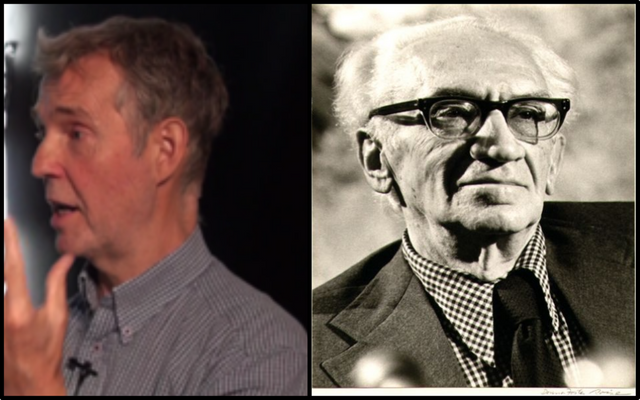

Immanuel Velikovsky believed that the Philistines migrated from Cyprus to Canaan at around the same time as the Exodus—the end of Middle Cypriot III. Like the Hyksos and the Israelites, their migrations were accompanied by—and in part caused by—a natural catastrophe. In Canaan, they interbred with the Semitic Amalekites, taking on many of their characteristics:

Shortly after the great natural catastrophe the Philistines arrived from the island of Caphtor and occupied the coast of Canaan. They intermarried with the Amalekites, sought their favor, accepted their political leadership, provided them with metalwork and pottery, and, during the centuries that followed, lost more and more of their own spiritual heritage and became a hybrid nation. (Velikovsky 83)

Like Sweeney, Velikovsky identified Caphtor with Cyprus:

The Philistines came from the island of Caphtor (Deuteronomy 2:23; Amos 9:7; Jeremiah 47:4). Jeremiah speaks of the “Philistines, the remnants of the country of Caphtor.” By identifying the Philistines with Kreti and Pleti, Caphtor was identified as Crete. It will be more in accord with historical evidence if we understand Caphtor to be Cyprus. If Caphtor was not Cyprus, then no name for Cyprus and no mention of the island would be found in the Scriptures, and that would be unlikely because Cyprus is very close to Syria. The islands of Khitiim (Jeremiah 2:10; Ezekiel 27:6), usually identified as Cyprus, signified all the islands and coastlands of the west, Macedonia, and even Italy. Cf. article “Cyprus” in The Jewish Encyclopedia. (Velikovsky 201 fn 17)

It is possible that Caphtor originally referred to Minoan Crete, but the name was later transferred to Cyprus when refugees from the collapse of the so-called Minoan civilization of Crete settled in Cyprus. This initial collapse would be the one that occurred at the end of Middle Minoan IIB. The subsequent migration from Cyprus to Canaan would then have taken place at the end of Middle Minoan IIIB.

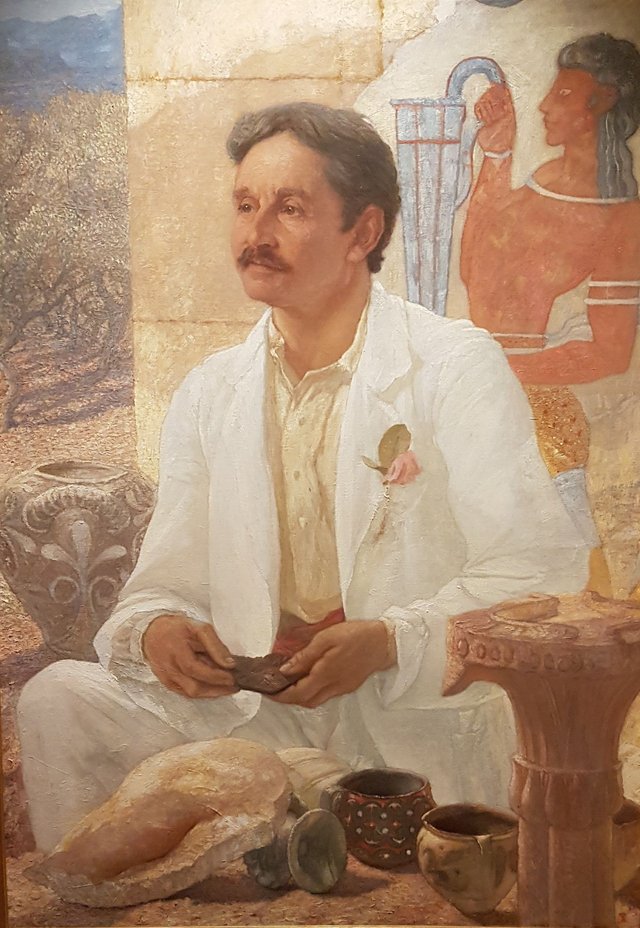

The hypothesis that the Philistines were originally Minoan Cretans was first proposed by the archaeologist who discovered and named the Minoan Civilization, Arthur Evans, though he believed that both Cyprus and Canaan—among other places—were colonized by Minoans directly from Crete:

We have seen that the diffusion of Late Minoan settlements along the South-Eastern shores of the Mediterranean best explains the appearance of the pre-Hellenic forms in the Anatolian alphabets, while in Cyprus it unquestionably brought about the early introduction of a highly developed linear syllabary.

But Cyprus was not the furthest goal of this colonizing enterprise from the Aegean side. It was rather, perhaps, the ἀφορμή [pretext] for that further advance to the extreme South-East Mediterranean angle which was to attach the name of Palestine to a large tract of the Canaanite littoral. It must at any rate be regarded as a remarkable coincidence that the close of the same period is marked in Canaan itself by the appearance of a system of linear script, wholly unconnected with the Semitic cuneiform, but presenting many points of correspondence with the Minoan signaries—in other words, the Phoenician alphabet.

The participation of a large Cretan contingent in the Philistine conquests of Southern Canaan is well ascertained. Among the leading members of the confederacy were the Cherethim, who appear as Κρῆτες [Krētes] in the Septuagint, [Zephaniah 2:5, Ezra 25:16] and even, by a not unnatural ethnographical anachronism, as Ἕλληνες [Hellēnes, Isaiah 9:12]. We read of these as holding the Southern district towards the Egyptian border, while the kindred Purasati or Pulasati, who seem to have supplied the actual name of Philistines, were their Northern neighbours. The commercial instinct of the Cherethim is well brought out by the occupation of Gaza, lying on the trunk line of commerce between Syria and the Nile Valley, and forming at the same time the Mediterranean goal of the South Arabian trade route. Gaza itself bore in later times the title of Minoa and was the legendary foundation of Minos and his brethren. Its chief God Marnas, ‛the Lord,’ was identified with Zeus Krêtagênes [Zeus the Crete-Born], and, though the evidence of this cult first emerges at a late date, there does not seem to be any sufficient ground for disputing its antiquity. The connexion, indeed, of the Philistines with Crete stands now on a very different footing from that which it formerly held when discussed by Hoeck, Stark, and other adverse critics. New and striking evidence has lately come to light in favour of the identification of the ‛Isle of Kaphtor’, the original seat of the Philistines, with the Keftô of Egyptian records, the Aegean home of the Keftiu. The most typical of the Philistine personal names, Achish, the LXX Ἀγχους, is twice repeated, under the form Akashou, in an Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian list which gives Keftiu names for the purposes of a school exercise. That the Keftiu themselves, such as we see them bearing tributary offerings to the officers of Thothmes III, are the characteristic representatives of Late Minoan culture, is no longer open to doubt. The fashions of their dress and hair, the offerings that they bear, the stately vases, the ingots and ox-heads of precious metal, reproduce the types in vogue in the latest Palace period at Knossos. It is to Kefts in their original Aegean home that the names of the Egyptian list refer, and the name of Achish may therefore have been rife in prehistoric Knossos before it was borne by a King of Gath. (Evans 77-78)

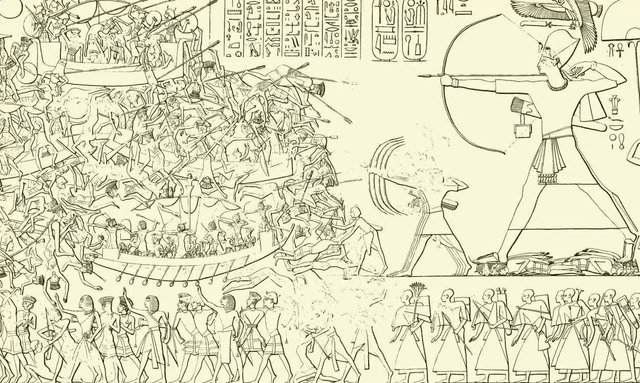

Evans’s dating of the Philistine conquest of southern Canaan to the 13th century is coloured by the conventional Egyptian chronology. In the above quotation the kindred Purasati or Pulasati refers to inscriptions from the reign of Ramesses III, who describes an invasion of the Egyptian Delta by the mysterious Sea Peoples, among whom were the Prwsṯ. The false chronology of mainstream archaeology has led Egyptologists to misread this as Plwsṯ, Pulasati or Peleset, to facilitate identification with the Philistines.

In The Peoples of the Sea, the concluding volume of his Ages in Chaos series, Immanuel Velikovsky has shown that the Sea Peoples were actually mercenaries employed by the Persian Emperors Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III to reconquer Lower Egypt following a successful revolt by the native Egyptians around 400 BCE. The hieroglyphs which archaeologists have read as Peleset and interpreted as a reference to the Philistines should really be read as Pereset, referring to the Persians. Ramesses III, the most famous Pharaoh of this period, reigned in the 4th century, not the 13th.

In Velikovsky’s opinion, the Philistine Conquest took place at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, contemporaneous with the Expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt, the Exodus of the House of Israel, and the rise of the 18th Dynasty. In the post-Velikovsky model of the Short Chronology that I am following, this would have been around 763 BCE—the actual year to which I tentatively date the Exodus.

Bronze or Iron?

Putting aside for the moment any discussion of absolute chronology, there is still an undeniable discrepancy between the relative dating of Velikovsky’s hypothesis and that of mainstream archaeology. He places the Philistine Conquest at the interface between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, whereas mainstream archaeologists place it between the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age I. The discrepancy between these two models can not be ignored. In the conventional chronology, the Late Bronze Age in southern Canaan lasted several centuries, being dated from 1550 to 1189 BCE—from the beginning of the 18th Dynasty to the end of the 19th Dynasty. In the Short Chronology, the events that bookend the Late Bronze Age are dated tentatively to 763 and 525 BCE. Either way, we have more than two centuries to bridge.

My initial response is that the conventional model is another artifact of the muddled chronology of mainstream archaeology. They have misinterpreted the Plwsṯ as Philistines, and then compounded their error by placing Ramesses III at the start of the Iron Age.

Recently it has become increasingly clear that there was no great break in Philistine culture at the end of the Late Bronze Age, as is required by mainstream archaeology. Many features thought to be characteristic of Philistine culture were already in place during the Late Bronze Age:

Whereas Aegean cultural influence cannot be denied, the continuity with the Late Bronze traditions in Philistia has increasingly come to attention. A number of Iron Age I features which were thought to be imported by the Philistines have been shown to have Late Bronze Age antecedents. (Ehrlich 10)

On the other hand, the DNA evidence suggests that the influx of European settlers occurred at the end of the Late Bronze Age:

The ancient Mediterranean port city of Ashkelon, identified as “Philistine” during the Iron Age, underwent a marked cultural change between the Late Bronze and the early Iron Age. It has been long debated whether this change was driven by a substantial movement of people, possibly linked to a larger migration of the so-called “Sea Peoples.” Here, we report genome-wide data of 10 Bronze and Iron Age individuals from Ashkelon. We find that the early Iron Age population was genetically distinct due to a European-related admixture. This genetic signal is no longer detectable in the later Iron Age population. Our results support that a migration event occurred during the Bronze to Iron Age transition in Ashkelon but did not leave a long-lasting genetic signature. (Feldman 1)

The authors of this study accept the mainstream view that the Peleset of Ramesses III were the Philistines of the 12th century BCE. But even if we reject their absolute chronology, we must still respect their relative chronology. Even in the Short Chronology, the end of the Late Bronze Age takes us down to the end of the 19th Dynasty and the beginning of the Persian Period.

But if the Philistines actually colonized southern Canaan around the time that the Hyksos were being expelled from Egypt, ought there not be clear references to them in the records of the 18th Dynasty, a Late Bronze Age dynasty? Are there?

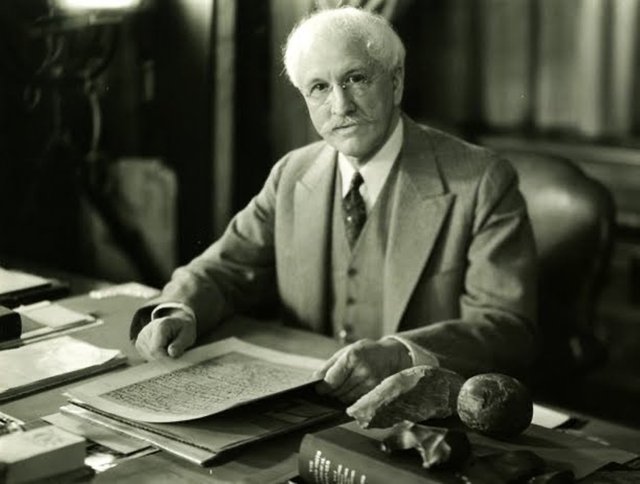

Not really. In his Ancient Records of Egypt, James Henry Breasted notes that Tuthmosis III mentions Gaza, one of the five principal cities of Philistia, during his First Campaign, but he does not mention any Philistines. In fact, Gaza is described as an Egyptian possession:

417 Year 23, first (month) of the third season (ninth month), on the fourth day, the day of the feast of the king’s coronation, (he arrived) at the city, the possession of the ruler, Gaza ... (Breasted 179)

Hans Jacob Katzenstein of the Schocken Institute for Jewish Research in Jerusalem translates the possession of the ruler as That-Which-the Ruler-Seized, but concedes that Gaza had probably been an Egyptian stronghold since the time of the first Pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty (Katzenstein 111-112). Katzenstein documents several other references to Gaza during the 18th and 19th Dynasties, but in none of them is there any mention of Philistines. Breasted does not record any 18th-Dynasty references to the other four cities of Philistia.

So when do we find Egyptian references to the Philistines? If we reject as spurious all the allusions to the so-called Peleset or Pulasati, then we are left with no mention of the Philistines anywhere in native Egyptian records. Mainstream archaeologists would probably cite this as evidence that Peleset must refer to the Philistines after all, but I find Velikovsky’s theory on the true identities of the Sea Peoples and the Pereset indefeasible.

The El Amarna Correspondence

One of the most valuable sources of information for the international relations between the 18th Dynasty and its neighbours is the Amarna Archive, a collection of 382 clay tablets recording the diplomatic correspondence between two Egyptian Pharaohs (Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten) and the leaders of several foreign cities and kingdoms. What do these letters have to say about the five cities of Philistia: Ashkelon, Gaza, Ashdod, Ekron and Gath?

Seven of the Amarna Letters—EA 320-326—were sent to the Pharaoh by the king of Ashkelon, Yidya. Another letter, EA 370, was sent from the Pharaoh to Yidya. It is clear from these letters that Ashkelon was an Egyptian vassal state at the time, but little more than this is revealed.

EA 296 was sent by the King of Gaza—or perhaps another, unidentified city—whose name is variously transcribed as Iahtiri, Yahtiru, or Yabitiri.

A city called Gimti—also read as Ginti, Gintu, and Giti—is mentioned at least five times in the Amarna Letters. This has been identified by some scholars with Gath, but this is speculative. Two correspondents, Shuwardata and Abdi-Ashirta have been proposed as rulers of this city.

Mainstream archaeologists regard these vassal rulers as Canaanites, but is there anything in these texts to exclude the possibility that were Philistines? In the Bible the rulers of the Philistine cities are referred to by the Hebrew word סֶרֶן [seren]—lord, ruler, tyrant—and not the word usually reserved for kings, מֶלֶךְ [mélekh]. The former is of uncertain etymology. It may be a Philistine term. In the Bible it is usually translated as lord, which suggests that the rulers of the five cities of Philistia were vassals.

Conclusion

The history of the Philistines will remain hidden behind a veil of uncertainty so long as mainstream archaeologists continue to confound them with the Pereset of Ramesses III. Nevertheless, we may hazard some general observations.

Did the Philistines colonize southern Canaan from Crete or from Cyprus? The answer to this question could have a significant bearing on the history of this mysterious nation. The archaeological evidence suggests that intercourse between Cyprus and Canaan began in earnest in Middle Cypriot II, peaked during Middle Cypriot III, and tapered off during the Late Cypriot I (Edwards 174). This supports Sweeney and Velikovsky’s hypothesis, according to which the Philistines colonized Canaan from Cyprus at the end of Middle Cypriot III—ie the end of the Middle Bronze Age. But if the Philistines came directly from Crete, this line of reasoning is no longer relevant.

The Cretan theory is supported by the genetic evidence. The DNA studies suggest that a significant influx of settlers from southern Europe took place in Ashkelon at the end of the Late Bronze Age, when intercourse between Cyprus and Canaan was at a low ebb.

This is a significant finding. If the Philistines did not settle in southern Canaan until after the 18th and 19th Dynasties had run their course, then we must question the validity of the Deuteronomistic History recorded in the early books of the Hebrew Bible. Conflict between the Israelites and Philistines would have to be moved several centuries forward into the Persian Period. Martin Noth’s theory hypothesizes that the Deuteronomistic History was concocted in the 6th century BCE by a Jewish scholar who wished to explain recent events in the history of the Israelites—the fall of Jerusalem and the Babylonian exile—using the theology and language of the Book of Deuteronomy. In the Short Chronology these events belong to the Persian Period.

Emmet Sweeney has elaborated on this theory, believing that the two Kingdoms of Israel and Judah developed parallel histories that describe contemporaneous events, but which came in time to be placed in succession:

We need also to consider the fact that after the initial conquest of Palestine by Tiglath-Pileser/Cyrus, numbers of Hebrews were continually being transported to Mesopotamia and the Median territories. With the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel during the time of Shalmaneser V/Cambyses and Sargon II/Darius I, huge numbers of Hebrews were transported eastwards. These persons did not, as many suppose, immediately lose their identity. On the contrary, as the Scriptures themselves make perfectly clear, they continued as a distinct culture and people for many years—surviving indeed until the arrival in exile of their Judaic cousins over a century later. During these years, the exiled Ten Tribes interacted with their Persian conquerors, and some of the books of the Old Testament deal with the fortunes of these exiles under the various Persian Great Kings.

However, even as the captive Israelites recorded their fortunes as exiles in Persia and Mesopotamia, the still free people of Judah also continued to keep records—records which told of their struggle for survival against the great power to the east which had already enslaved their Israelite cousins. The chroniclers of Judaic history however called this power and its kings by their Semitic names, whereas the chroniclers of the history of the exiled Israelites, living as they did in the Persian homeland, probably used the Persian names. Thus two parallel histories, one compiled by the free Jews, the other by the exiled Israelites, seem to have developed. When the Scriptures were being written in their final form, during the first century BC, the two distinct traditions were available. Clearly the use of totally different names for the same kings must have caused profound confusion, and eventually the parallel traditions were put in sequence rather than kept as they should have been, contemporary. The misplacement of Persian history also therefore had the effect of throwing Hebrew history into chaos. (Sweeney 2008:162)

The Philistines belong to the Persian Period.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- William Foxwell Albright, A Babylonian Geographical Treatise on Sargon of Akkad’s Empire, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Volume 45, Pages 193-245, American Oriental Society, Boston, Massachusetts (1925)

- James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Volumes 1-5, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1906)

- Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards et al (editors), The Cambridge Ancient History, Third Edition, Volume 2, Part 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1973)

- Carl S Ehrlich, The Philistines in Transition: A History from ca. 1000-730 B.C.E, E J Brill, Leiden (1996)

- Arthur Evans, Scripta Minoa, Volume 1, The Clarendon Press, Oxford (1909)

- Michal Feldman et al, Ancient DNA Sheds Light on the Genetic Origins of Early Iron Age Philistines, Science Advances, Volume 5, Issue 7, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, DC (2019)

id=ucm.5327352325&view=1up&seq=11), Réflexions Critiques sur l’Origine, l’Histoire et la Succession des Anciens Peuples Chaldéens, Hebreux, Phéniciens, Égyptiens, Grecs, &c., Jusqu’au Tems De Cyrus, Volume 2, De Bure l’Aîné, Paris (1747) - H Jacob Katzenstein, Gaza in the Egyptian Texts of the New Kingdom, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Volume 102, Number 1, Pages 111-113, American Oriental Society, Boston, Massachusetts (1982)

- John Victor Luce, The End of Atlantis: New Light on an Old Legend, Book Club Associates, London (1973)

- Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, The Philistines: Their History and Civilization, The Schweich Lectures 1911, The British Academy, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, London (1914)

- Archibald Henry Sayce, The “Higher Criticism” and the Verdict of the Monuments, Third Edition, Revised, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London (1894)

- Otto Schroeder, Keilschrifttexte aus Assur Verschiedenen Inhalts, J C Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig (1920)

- John Strange, Caphtor/Keftiu: A New Investigation,Acta Theologica Danica, Volume 14, E J Brill, Leiden (1980)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

- Emmet Sweeney, The Pyramid Age, Ages in Alignment, Volume 2, Algora Publishing, New York (2007)

- Emmet Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, From the Exodus to King Akhnaton, Ages in Chaos, Volume 1, Doubleday & Company, Inc, Garden City, New York (1952)

Image Credits

- The Plague of the Philistines at Ashdod: Pieter van Halen (artist), After Nicolas Poussin, Wellcome Collection, London, Public Domain

- R A S Macalister: Dermod O’Brien (artist), Royal Irish Academy, Academy House, Dublin, Public Domain

- Canaan in the Time of Saul: © David P Barrett (designer), Creative Commons License

- Gift Bearers from Keftiu: Nina de Garis Davies (artist), Facsimile of a Painting from the Tomb of Rekhmire, Upper Egypt, 18th Dynasty, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Public Domain

- Excavating the Philistine Cemetery at Ashkelon: Melissa Aja (photographer), © Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon, Fair Use

- Emmet Sweeney: © Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (SIS), Fair Use

- Immanuel Velikovsky: Donna Foster Roizen (photographer), © Frederic Jueneman, Creative Commons License

- International Trade Routes in the Bronze Age: © The Maritime History Podcast, Fair Use

- Sir Arthur Evans among the Ruins of the Palace of Knossos: William Blake Richmond (artist), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Gts-tg (photographer), Public Domain

- The Sea Peoples: Bas Relief Mural of Ramesses III, Medinet Habu, Luxor, Upper Egypt, Public Domain

- The Ruins of Gath (Tell es-Safi): © Ori~ (photographer), Creative Commons License

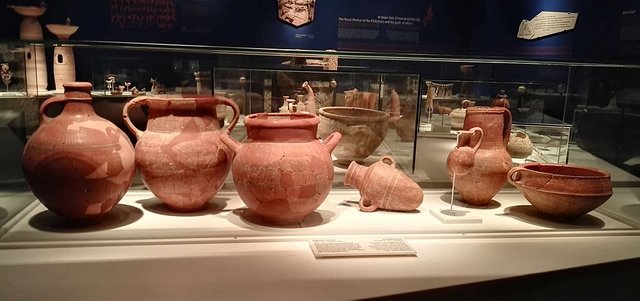

- Pottery from the Philistine City of Ashdod: Corinne Mamane Museum of Philistine Culture, Ashdod, Israel, © Bukvoed (photographer), Creative Commons License

- James Henry Breasted: The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, Public Domain

- Five El Amarna Letters: British Museum, London, © Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Bureau of Correspondence of Pharaoh, Tell el-Amarna: © Markh (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Ekron Royal Dedicatory Inscription: Israel Museum, Jerusalem, © Oren Rozen (photographer), Creative Commons License

- The Burning of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar’s Army: Circle of Juan de la Corte, Fundación Banco Santander, Madrid, Spain, Public Domain