Permaculture Ethics – How Does Hay Stack Up?

It’s winter, and we had an ice storm roll through last weekend. I slipped a bit on the slick sidewalk and twisted my back a bit so I’ve been mostly housebound. It’s just as well because it turned out warm and rainy, which turned the landscape into Rasputitsa, the Russian word for “season of mud.” This time of year in Northern Missouri there aren’t many things going on outdoors. The fields are fallow and mostly deserted. The occasional hunter, someone cutting firewood, and the man feeding hay to his livestock are all that dot this barren landscape.

Feeding hay in winter, as well as the corresponding making of hay in the summer have been a part of my existence since I was self-aware. The last couple of years, armed with new information I began to wonder about the efficiency of this system, it’s effects on the environment, and whether it is by and large necessary.

The Process – In short

The process of making hay is pretty simple when you break it down to steps. Making hay in it’s simplest form consists of mowing the forage, curing it, gathering it, storing it, and feeding it to animals. There are a lot of nuances in this system, and some places where, in the current model, we trade fossil fuel for hay. I hope to look at each of those nuances independently and see if they pass muster.

Past practices

Mowing: Historically hay has been mowed with a scythe, which was invented sometime around 500BC, and widely used until midway through the 20th century. In the latter half of the 19th century horse-drawn mowers came onto the scene, speeding the process up dramatically.

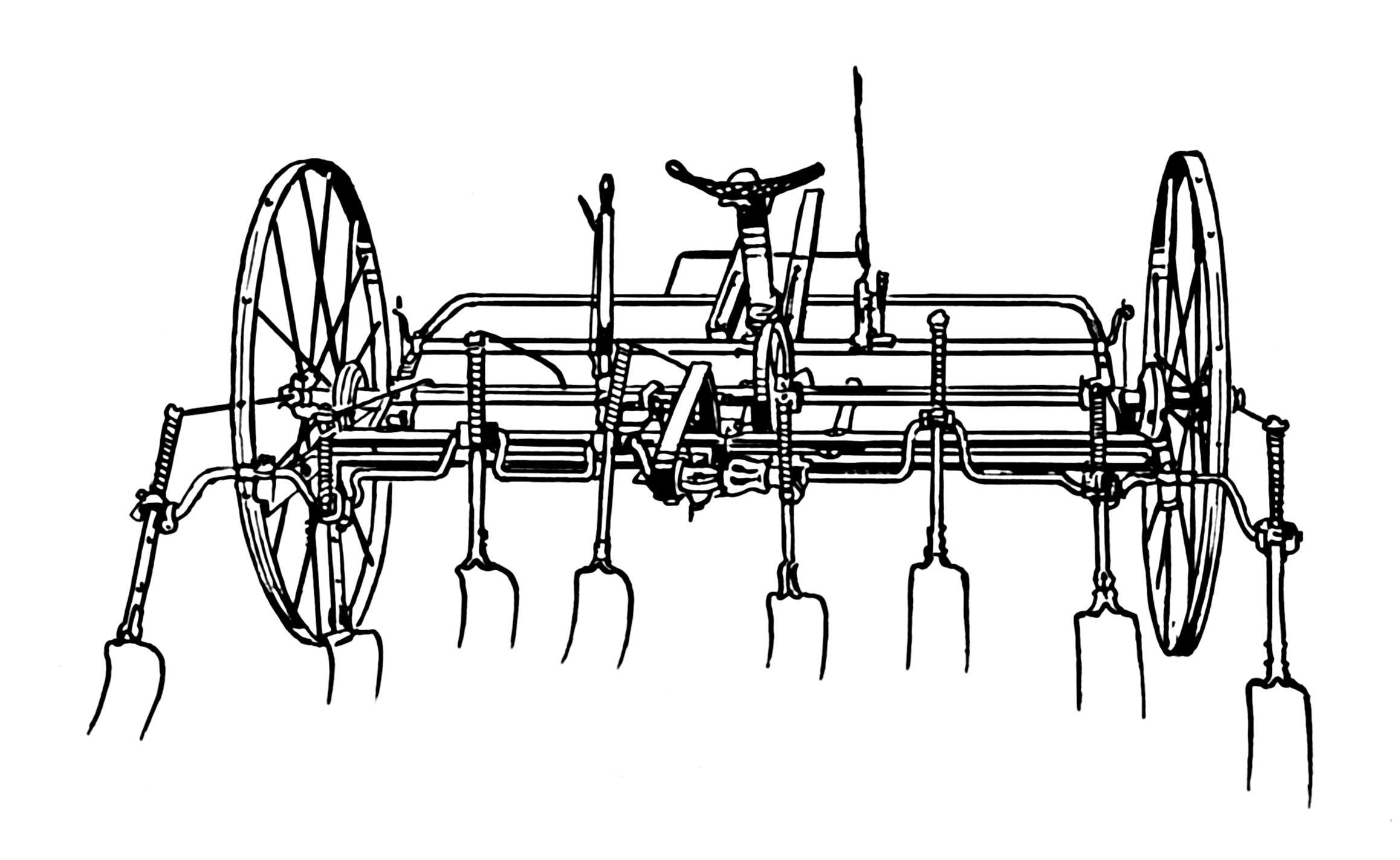

Curing: Once mowed the forage was left lying on the ground to cure in the sun. If the weather was uncooperative then the drying forage might be turned with a hay fork or hand rake of some sort. This also might be used to speed the drying time, sometimes to within a day. Coinciding roughly with the invention of the horse-drawn sickle mower, was the invention of a horse drawn implement known as a Tedder. This device sped the process up dramatically, and was described as doing the job of “15 men.”

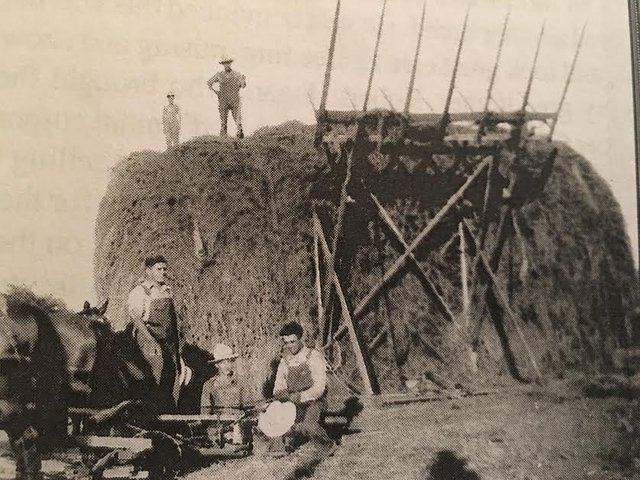

Gathering: After the forage has cured, it has officially “become” hay. The next step is gathering. Historically there were a lot of rakes involved. Having been mowed, hay was gathered into piles and in some cases those piles were combined into larger piles called haystacks. The hay was piled in such a manner that the top layers shed water to the sides, least they become a giant pile of compost, and most generally they were shaped like a dome or loaf of bread. In cases where they were larger than the height of a man there were a variety of means and machines used to pull the hay higher and higher. One such device I have heard called a “ricker fork,” but I have been unable to find any further information regarding it or it’s use aside from it being a horse-drawn device used to elevate a pile of hay to the top of a haystack. Hand held rakes gave way to horse drawn hay rakes starting in the mid 19th century, but rather than just making piles to be gathered, they created a long thin pile known as a windrow. With a tool called a hay loader (a highly original name) which towed behind a wagon, a farmer could lead a team of horses along the windrow and the hay loader would pull the windrow up and plop it up onto the wagon. One or two men with a pitch fork to distribute the load was far less than was required prior to this innovation.

A “ricker fork” as described in a book from my own family history.

Where the game changed altogether, was with the invention of the hay baler. It started with the small square baler, producing a rectangular bale approximately three feet in length and fourteen inches wide. This put the mass of hay into the range of easily handled by one person at about 40 to sixty pounds, and got rid of the need of carrying a pitchfork everywhere. This, alongside its round (though slightly larger) counterpart was the standard from the 1950s to the 1970s. Then came the large round baler. This device made a larger version of the small round bale, at approximately 800 pounds it was considerably larger and was only possible because the tractors of the day were able to handle such a load. Around the same time as the development of the large round baler there was a device called a stacker, which collected loose hay and compressed them into medium sized hay-stacks. This was eventually outcompeted by the round baler as the portability of stacked hay wasn’t acceptable next to baled hay. Until baled hay became mainstream, the portability of hay wasn’t even a consideration as it was put up near where it was fed out. Baled hay changed that paradigm.

Storing: Storage of hay was done in an either inside or outside fashion. When hay was put up into small haystacks and scattered throughout the landscape, there weren’t any plastic tarps available cheaply to cover them, so the stacks were designed to naturally shed water. Mounded on the top, and sometimes covered in sedge grasses, which shed water exceptionally well, the top layers acted like a thatch roof. As technology got greater, and out of convenience, hay began being stored in larger piles, and then inside the upper stories of barns. Barns, as they went, evolved in design to accommodate larger piles of hay, until the “hay loft” area of most barns became the largest space in many American barns.

Once baled hay came onto the farms, it became apparent that hay could no longer be stored outside. Small round bales could shed water much like a haystack, but with their diminutive size the amount of loss and decay around the edges exposed to the edges was significant. The square bales were shaped in such a way that moisture would quickly saturate the forage and cause decay. Thus the hay lofts above most existing barns found themselves piled with bales of hay rather than mounds of hay. It wasn’t a significant change. Soon after, specialized hay barns sprouted up all over the landscape. These pole structures had no walls, just a roof to keep most of the water off, and ample space to pile hay bales. This occurred because baled hay had become a transportable commodity, and farmers began building surpluses for later use, or for sale. The size of large round bales presented somewhat of a challenge, though it was discovered that they, like haystacks that proceeded them, shed water adequately to remain stored outside. Thus they were butted up, end to end in long rows to stay fresher.

Feeding: Feeding of hay is maybe the “no-brainer” part of the process. We have accumulated all of this material, now what do we do? Initially the smaller haystacks maybe had been fenced off from the livestock in some manner, and the haystacks were either exposed directly to the livestock or the stack was pitched to the livestock. Larger haystacks were pieced out and hauled on wagons in the correct proportions to feed however many livestock were needed. Both of these previous practices put the nutrients from the hay more or less directly back where they came from, minus any nutrients that were to wash away. This practice of returning the nutrients to the fields where they came from continued somewhat as baled hay became the dominant medium, but has diminished slowly as a general practice over the last two generations.

Hay kept loose in barns was either fed directly at the site in stalls or nearby pens, or hauled out into the nearby fields to be fed to livestock there. The first practice led to an accumulation of nutrients around the barnyard areas, sometimes to the level of pollution. However, practices in that time period made good use of those nutrients by relocating and utilizing them in gardens and fields. That use became less relevant into modern times. Baled hay stored in place of loose hay in barn lofts found itself used in much the same manner as its loosely stored predecessor, except that it was much more easy and convenient to move in large quantities.

Current Practices

So what’s changed since those days? The basics are the same, but the details differ slightly.

Mowing: This is now done almost exclusively by tractor with attached mower or by self-propelled mower. There are mowers with rollers which crimp the forage as it is mowed, which causes the stalk of the forage plant to cure more quickly. These devices are usually referred to as mower conditioners. The obvious difference is simply the amount of acres a single person can cover in a given day, as opposed to an acre or two with horse drawn mower.

Curing: Much the same as before, it either dries on the ground or is stirred and fluffed with a tedder. Modern tedders are pulled by tractor and can cover many acres in a very short amount of time.

Gathering: Once the hay is cut and cured, a tractor pulls a rake through the field. Modern rakes are almost exclusively a one pass design, where previous designs required two passes across a field in order to create a windrow. Once the hay has been windrowed up, a tractor pulls a baler through the field, straddling and sucking it up and compressing it into a bale. Round bales are now in the 1000 to 1800 pound range, and wrapped in plastic net wrap. There are now large square balers, which create rectangular bales weighing between 1000 and 2000 pounds and used for easy transportation of large amounts of hay.

Storing: Round bales are still stored in long rows, butted end to end, generally outdoors. Square bales are still stored inside barns, and occasionally in large piles on the ground, covered in large tarps.

A line of stored round bales.

Feeding: Feeding round bales is a little more complicated than just picking the bale up with a tractor and plopping it down in front of the livestock. Round bales can be unrolled, leaving long strings of hay for livestock to eat. However, typical handling equipment on tractors is not equipped for unrolling hay bales, nor is it easy to accomplish without the correct equipment. However, there are specialized devices called, unimaginatively, bale unrollers. Mounted to tractors, and in some cases trucks, these devices grasp the bale across its central axis with two arms. On swivels the bale simply unrolls. Another practice is a bale processor, which is a machine that takes an entire bale, grinds it up into small bits, and blows it out into a pile, or more often a windrow. The only issue with this and unrolling the bale is that livestock tend to waste quite a bit of hay as they step, urinate, and defecate on the same hay, making it inedible. Another means of feeding hay is to simply place it into a feed bunk or bale ring. This keeps the animal off the top of its feed.

Alternative Practices

There are additional tactics used in the battle to procure and feed hay. Irrigation exists in certain areas where forage doesn’t grow well on natural rainfall, though this is usually only the case with high value forages such as alfalfa. Another technology that was put into use in the last two decades is the use of antifungals sprayed into the mouth of the baler which allows one to bale hay normally too wet.

Why Go to All This Trouble in the First Place?

The simple answer to this is to feed a large amount of livestock. Raising livestock usually isn’t an altruistic practice, so obviously there’s a financial incentive to doing so, and more livestock means more potential for profit.

Three Ethics

Motivations being capitalistic, the unforseen consequences of parts of this process don’t necessarily match up with our overall desire to leave the world better than we left it. Thus here is my best attempt at judging our practices against the Three Ethics of Permaculture. I chose Permaculture as the barometer because it’s the centerpiece in many regenerative agriculturalists table of philosophies. Also, it takes ethics away from specific faiths and religions and puts it into a human context that is fairly universal. In other words, this should apply to anyone. Step by step we will weigh each process, both past and present, and see whether we can say that the Ethic is being met.

Care of Earth

In the spirit of this Ethic, we hope to create something worthwhile instead of creating harm, or at least MORE benefit than harm. Our history is riddled with instances of more harm than good, which is part of the reason we find ourselves in this current predicament. How, does the process of procuring, storing, and feeding of hay address the first ethic?

Mowing: Mowing itself isn’t terribly destructive to the landscape. Rarely, we see any break in the vegetation, like tillage might do. Often, areas where hay is being mowed is relatively devoid of many larger life forms. The act of cutting the vegetation is not without disruption to the subsoil however. Plants cut of their upper portions do what is called “root pruning” wherein a comparable amount of root system dies off to balance the plants presence in both atmosphere and rhizosphere. The original act of creating a hay field may have been destructive to the environment as there was something like a forest there, but likely that occurred in generations past. Mowing opens up areas which may be choked with low lying vegetation to the sun, allowing for thicker growth of grass plants. (Ben Falk mentions this in his book The Resilient Farm and Homestead). Mowing also holds a landscape into one form, good or bad, rather than succeeding to another form of vegetation (such as scrub or forest.) Modern mowing uses a lot of fossil fuel to accomplish this tactic, and the farmer covers so much area with such a large machine that the fields have been made bigger and wildlife is allowed fewer edges or fringes to inhabit.

Curing is rather passive. It doesn’t particularly cause any particular issues to the Earth or its inhabitants. Tedding with pitch forks and rakes, or with horses, is not particularly destructive either. Tedding with a tractor drawn implement has the obvious effect of burning fuels and all that brings about, but also has an added tendency to make an occasional gouge into the soil as tines spinning at fantastic speeds happen to come into contact at the wrong angle. Still, this isn’t noteworthy harm overall.

Raking by hand or by horse is again, relatively passive. Machinery as always encounters fuel usage, and raking as an action with modern machinery often drags a series of metal tines across the somewhat denuded ground as it passes. This is somewhat of a harrowing process, and likely buries grass seed as it passes, aerating the soil surface as it goes, and in a sense reseeding the area for future crops.

Baling uses fossil fuels, period. There are no ground driven hay balers as there are other machines, and as such the need for a tractor or mounted engine as some early balers had, is necessary for the inertia needed to compress the bale into a convenient shape for transport and storage. It’s pressures on the land are no greater than any other piece of equipment, thus it’s fuel burden is the only consideration.

Storing is again relatively passive. Some fuel might be used in moving hay to storage locations, but the overall storage isn’t damaging or helpful either way. Stored hay might actually act as habitat in some manners for mice, raccoons, weasels, or whatever creature may happen by. On outside piles of hay there are often bits of hay which fall off of the bales both during the piling process and progressively during the feeding process. As such areas prone to hay storage often have a deep rich topsoil.

Feeding hay can be both good and bad. The hay coming from a wagon, having been stored loose in a haystack or hay loft is neutral. It has no harmful side effects. Once plopped out onto the ground the livestock begins to digest it. Baled hay can come to the livestock in many forms, nearly all of which need fuel, and are deposited in one form or another before the livestock, which digest the hay and deposit the nutrients wherever they happen to be. Here is where the hay feeding gets complicated. In areas where the ground freezes, too much manure gets washed off the hillsides and into aquifers where it contributes to ground water issues. In other areas, the manure may become thick enough to actually choke out vegetation, which begins the process of succession wherein weeds colonize what they consider open soil. In a large enough area this tends to completely destabilize a forage crop, which is expensive to replant. A farmer needs to think carefully about where his water supply is in relation to his feeding areas, as in hilly regions water is typically at or near the bottom of a hill and the level ground is at or near the top of a hill. In this scenario it could be very easy to despoil a water supply by manure runoff.

By and large the impact of hay is not terribly destructive toward the Earth. However, improper handling of an overabundance of manure can be destructive. Steps must be taken to keep from one of the best sources of natural fertilizer becoming a pollutant.

Care of People

The history of the western culture has a long list of offenses toward other human beings. These offenses are a stain upon our path and steps need to be made in order to ensure that things of this nature don’t occur again. Thus how, does the process of procuring, storing, and feeding of hay address the second ethic?

- Mowing has always been guided and done by human beings, thus it is a task which requires at least one person, who then cannot do something else. Mowing with a scythe, a horse drawn mower, a tractor drawn mower, or even a self propelled mower still requires one person to do it.

- Curing is irrelevant to humans because its a natural process. Tedding, or fluffing of the hay is another process which requires one person to do it, but the more mechanized the process, the more that one person can do.

- Raking, done by hand, by horse, or by tractor is still requiring one person to do it.

- Whether piling, pitching, or baling, there’s still a human element required. Less people are required for the baling of hay, but in the case of small square bales more people are required to pick the bales up and deposit them into a barn than are required to gather and situate round bales into long rows with a tractor.

- Feeding by hand was often an all day task when it was done with pitchfork, wagon, and horse. Now that task is primarily done from inside a warm tractor or truck cab, much quicker than was ever possible with a pitchfork.

Overall, the hay making process is not harmful to human beings. The work can be oppressive and people COULD be exploited into doing it, but the process itself isn’t terrible. There aren’t many health concerns aside from excessive hay dust installation and that could be addressed with a simple face mask. And ultimately hay is made because we as human beings cannot digest forage, but specific animals can. Thus we can convert inedible forage into an edible protein source, and not starving is decidedly pro-human. So long as the feeding process doesn’t overwhelm the environmental ability of the local flora to soak up excess nutrients from manure, and thus pollutes the water supply, this is a neutral to leaning toward positive process when it comes to people care. Where things take somewhat of a wrong turn is that with all the new machinery, we are isolated. We are isolated from each other, from the nature that we interact with, from sounds and smells, and even the outside temperature. We now sit in cubicles which move, listening to FM radio to drown out the sound of the engine, and pass by acres and acres without really seeing them as we do on the ground, all at a mild and comfortable 72 degrees Fahrenheit.

Return of Surplus

How, does the process of procuring, storing, and feeding of hay address the third ethic? There isn’t a lot of surplus to return here, but what surplus exists, has usually been thought of as an afterthought if at all. Seed from mature plants fall to the ground during the mowing process, and are beat off of the dry seed heads during the tedding and raking processes. I have seen situations where certain types of mowers inadvertently collect seed on top of them which can be swept into buckets or bags for later use. I have also seen situations where the machine is covered in grasshoppers and if a properly shaped collector were employed, such a collection would net a huge protein source for someone who has chickens or other fowl to feed. The biomass and nutrients ends up relatively close to where the hay is fed to livestock, and care must be taken to ensure that it gets absorbed back into the soil. Most hay comes from one area, and is fed in another, while chemical fertilizer is added to the first area to compensate. This is a violation of the third ethic because unused surplus becomes pollution in one area, and depletion in another.

There is no way to recover any of the fuel employed in any of these actions directly, so that is totally lost to entropy. In a future where fossil fuels are scarce and expensive, those who come after us may judge us for squandering fuels on something so seasonal when we should have been using it for more permanent solutions.

Possible Alternatives

There aren’t a ton of violations to the Three Ethics here to address really, but there is a very poignant question which few seem to be asking. Do we need hay? The answer to that isn’t as simple as one might think.

For instance, American Bison roamed the plains and grazed year round, and they numbered into the hundreds of thousands. No one fed them hay until someone tried to domesticate a few of them. The Auroch, or European Ox, ancestor to all of the cattle breeds that are currently raised in north America lived in much the same manner until its documented extinction in 1627, and no one fed them either. So do we need to actually feed our livestock, or simply ensure that they have an appropriate amount of forage to eat for themselves?

Farmer, Greg Judy believes that you can graze cattle year round. Greg lives is in zone 5, in Central Missouri and he doesn’t own a tractor. He doesn’t own a baler. He doesn’t even own much land. He doesn’t have any of the infrastructure that mainstream agriculture says is needed to raise livestock, yet he owns a herd of over two hundred fifty head, along with sheep, hogs, and several horses. How does he do this? Simple. He does some math. By calculating what each head of livestock are required in their diet, he can estimate how much forage is required by the herd at large. He can then paddock off small pens using electric fence and give them fresh pasture on a regular basis. Many people practice this, but where he differs is that he doesn’t stop when the leaves fall in the autumn. When the snow falls he just keeps on moving fences and his herds seem to get along just fine. Where he says he runs into trouble, is not with snow, but with heavy ice, which effectively glues forage to the ground. At that point he feeds some bought hay and gets through what may be a week or less of unfavorable conditions. Its safe to say he feeds a 20th or less per head than many farmers. That model is almost within the realm of scythe and pitchfork, if push came to shove. This model ensures that manure is adequately spread out to be reabsorbed into the soil. It also allows livestock to continue to maintain or gain weight in winter, which is something that doesn’t usually happen on hay. For some reason, that dead forage on the ground seems to have more nutrition than hay, and keeps the animal healthier. And best of all, Greg uses VERY little fossil fuel. Now arguably, Greg isn’t in Northern Montana. If what he says is true about snow, unless the snow becomes too deep, the same rules apply there as do in Missouri and even they could cut down their hay usage to a fraction of what is needed now. Someone will need to test this theory, as that’s just speculation at this point, but it’s a worthy goal in my opinion.

Anecdotal evidence on my part has also led me to believe that modern farmers waste hay in immense amounts. Part of it is the way in which the hay is baled into these huge round cylinders, and the cattle end up trampling or lying on some of it. But largely I think that they simply overfeed the cattle because its so convenient. My dad tells me that in the early 1970s when he was a teenager that they put up square bales. A square bale weighs between 45 and 55 pounds typically (so lets say 50 for simplicity’s sake), and it was understood that every cow and ever calf got one half of a bale per day, so you took your total herd population and divided by two to determine how many bales to feed. Simple, right? Another way to calculate that is called Animal Units. This is when you take the entire estimated weight of the herd and divide that by 1000. Every 1000 pounds of bovine is considered one unit, even if there are cows which weigh 2000 pounds, or 600 pounds (together that would be 2.6 animal units). Now modern hay bales weigh between 1500 to 1800 pounds. By that 25 pound per head mantra that means that one round bale SHOULD feed in the area of 60 to 72 animal units per bale. Somehow that doesn’t play out and a herd with 60 head will often get rationed two or even three bales. In my opinion, when hay was much more expensive in terms of labor it was used much more efficiently. I sometimes wonder if farmers from 75 years ago would be appalled at the amount of hay we put up and waste. I also wonder if our great grandchildren will as well.

An interesting and rich article on something I didn't know was so complicated. Thanks for sharing your work

Thank you!

Very impressive article

please upvote me and follow me @rahmadharun93

I dont ofen do that, asking for it is bad form. I did look at your blog and saw that you have some interesting posts, so Ive followed you

Oh my! That was so brilliant. That was so comprehensive. That was so informative.

If I had such large brain, I would break this into a two part series to be sure I don't lose the shorter-attention-span folks who could use this information too. I mean it is enough information to take in two servings.

Seems you had a 7 month hiatus from Steem, @agsurrection. I hope you resurrected for good to continue to contribute your great knowledge to this platform. You rock!

Following you...

Thank you for such praise! I probably should have cut it into two pieces, but it got away from me somehow. I hope to contribute more, just hadn't had the time until lately.

Hi @agsurrection.

I used to run a dairy farm about 10 years ago. We never had the problem feeding our cattle because we were using fresh grass to feed them together with Palm Kernel Cake.

I heard about hay but never had the chance of making it. Thank you for telling us how.

Hope that you will get well soon.

Thank you for sharing.

I had not considered what cattle are fed in an environment where there is no winter. I would think palm kernel cake would be high in protein and low in carbohydrate. Is that correct?

Yes. It's good for a dairy cow to produce more milk.

Is that to supplement production on top of what the cow grazes, or is that the primary part of their diet?

It is part of their main diet. It is so easy to get PKC here in North Borneo. But the downside of doing this type of business here is low milk production.

I love this article, the concept of permaculture. You've given me a new tag to follow. Your minute attention to consequences at every step is refreshing. I notice, when proponents of different energy sources compare consequences, they limit those to direct result of use. They rarely speak about the exploitation of resources, including natural and human, that go into mining, or creating, the energy. One question that may be stupid: is forage planted specifically for hay production and if so, what is it? Great post. I've shared it on Twitter.

In some cases it IS planted specifically for forage, but in terms of resources going into it, this is relatively low impact in most cases. These plants are typically either self-seeding annuals, biannuals (which often self-seed and whose seed doesn't all germinate in the same year), or perennials.

In some locations forages are just what grows naturally, and these have the lowest environmental impact.

Encroachment from hardy perennial shrubs and trees around edges is eliminated with annual mowing, and most "weeds" require bare soil to germinate, so stands of these forages CAN last as long as twenty to thirty years.

There are less than satisfactory forages in less than satisfactory places that sort of push against the ethics and skew any judgements about forages and hay in general. One such crop is Alfalfa, raised in the American southwest, irrigated with water from fossil aquifers, fertilized to promote growth, and sprayed with chemicals to ensure that it's JUST alfalfa. This is just as bad as any other cash-crop in America.

I do appreciate your sharing this. Thank you!

Hello @agsurrection

I liked your post and I mentioned it in [Curation 04/02] Four posts of minnows that I think are worth voting

Please consider voting this comment to help me continue doing this curation work and supporting minnows.

Thank you very much! I appreciate the praise and the attention.

So. I live in the west where things are vastly different. The waste is much worse in most ways. Except, perhaps, where grazing is concerned. There are a few really good ranchers that treat their land and leased land as if they were inhabited by the buffalo still. Keep the herd mostly moving and improve the land at the same time.

Some where near 100% of the hay in the southwest is alfalfa. Irrigated alfalfa. Specifically for me, Colorado River water. The Colorado has a host of problems related to too many people dependent on too little water, and alfalfa contributes mightily to that.

There are multiple monstrous hay operations owned by foreign nationals or in a couple of cases foreign governments that use Colorado River water to grow hay entirely for export. So, in effect, we are using our most precious and pressing commodity to subsidize protein and dairy production in foreign countries. Incredibly unsustainable.

Some of the hay production could be handled much differently today. Electric mowers and balers would be quite easy to build, and one thing the southwest has in abundance is sunshine. A lot could be done to maximize our current practices.

All in all a really good article. Well thought and written. Thank you for all your effort.

I began to include irrigated alfalfa into the article, but I found I really don't know much about it, aside from driving by some in west Texas a few years back. Irrigated crops, whether grain or forage, in my opinion is an egregious waste of resources all around. There is also apparently a great deal of fertilizer involved in the growing of alfalfa for sale, because it tends to strip a lot of minerals out of the soil.

I had not considered electric mowers or balers, but I do think that automation is going to take over the mechanical part of agriculture in the immediate future anyway, so that's a logical progression anyhow.

Thank you for the praise. I hope to write more, as I have a little more time on my hands.

Alfalfa is actually a legume so it fixes nitrogen and essentially does not deplete the soil at all. Micro nutrients only. But it takes a lot of water.

It's going to take a major cultural shift to slow up irrigated farming. Such a high percentage of commercial ag is irrigated.

I believe alfalfa pulls off a lot of potassium, if I recall my HS agronomy class correctly. Also, even though it's a legume, most farmers apply a bit of nitrogen between cutting to push growth for swift recutting (at least around here, though it's not irrigated here).

Sadly the issues with commercial ag won't be resolved until its no longer (financially) advantageous to act so destructively.

Thats some good info. Thanks

THE BILLION COIN IS THE FINANCIAL LEVERAGE WE HAVE BEEN WAITING FOR. IT'S NOW A REALITY.

I HOPE YOU WILL CONSIDER GETTING SOME FOR YOURSELF

www.thebillioncoin.info

www.tbc004.net

blog.thebillioncoin.info

Very good information and knowledge..hope that everything will be okay..keep sharing ya..thankyou.

Much better now, thank you. And I will!

please upvote me and follow me @rahmadharun93

Nice updete