Will blockchain rattle the supermarkets?

Could blockchain and people power wipe out Tesco, Morrisons and Sainsbury’s? Could blockchain even have a pop at some of the supply chain behemoths that lie behind supermarket household names?

Imagine a world where veg, bread and other basics arrives from the maker direct. No middle man gouging out a cut. No more suppliers competing for shelf position. Or paying for their own promotions before giving a cut to the supermarket if targets are met (otherwise known as commercial income).

Instead, food makers and grocers sell direct via their own decentralised tech, straight to the customer’s fridge or cupboard. Then there’s the new logistics opportunities it could bring because until science cracks teleportation a tub of pesto can’t get to the fridge without help.

From field to fridge, new logistics opportunities could soon open up

From Russia with 30% off

Blockchain player INS may have an early lead here. It’s building an interface linking brands straight to UK consumers. The grocery industry in its current shape is inefficient and completely controlled by retailers says INS boss Peter Fedchenkov.

“For example, in the UK, there are over 7,000 manufacturers and 25 million households dependent on four key grocery retailers controlling 76% of the market. INS will adopt blockchain to cut the middleman – wholesalers and retail stores – to help consumers save up to 30% on grocery shopping.”

INS is not British or European. It’s a Russian start-up. Fedchenkov has an MBA from Harvard Business School and flogging groceries is in his genes. His grandfather’s own wholesale grocery business was hammered when the USSR imploded in the early 1990s. As distribution channels broke up all around, senior Fedchenkov was forced to re-think.

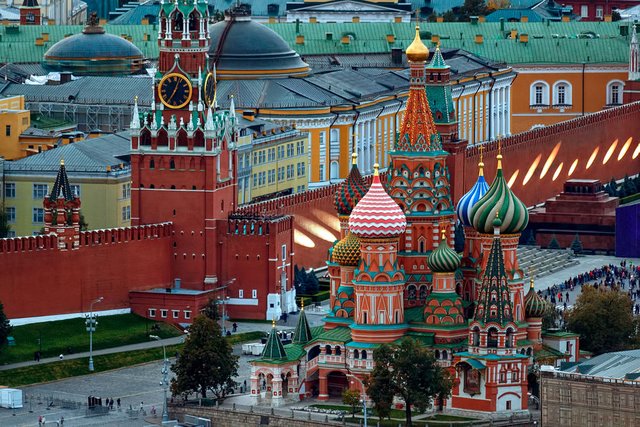

Looking towards St Basil’s Cathedral – the Russian retail landscape is changing at high speed

A mail-order system, selling direct via ads in regional Russian media and by-passing wholesalers, was born. Grandson Peter went onto re-work this approach online, creating online grocery business-to-consumer model, Instamart – Russia’s biggest online delivery business.

Millennial issues

INS’ claims of 30% savings are simply eye-watering when you consider that even by 2020 Tesco’s profit margins may not touch 4%.

Even without the blockchain threat, the grocery industry remains dominated by third-party retailers engrossed in a slow death-squeeze for margins and market share based on ageing legacy systems that are struggling to communicate with key customers, such as millennials.

Many don’t watch TV. They’re more likely to seek out independent local brands that support their own communities, according to some consumer trend analysts.

Millennials have a different mindset to consumerism – long term this will play out across many retail channels

Tiny range = strong profits

Meanwhile discounters, light on their feet thanks to tiny own-brand product ranges, punch hard where the bigger players are vulnerable – price. Stagnant wages and creeping, Brexit-inflicted food price inflation have given Aldi and Lidl a stiff following wind.

Yet all this is without a mention of the A-word. Amazon Web Services, the cloud-based subsidiary to Amazon.com, recently partnered with blockchain player Consensys to produce their own start-up love child, Kaleido.

Amazon had no interest in building up their own blockchain network from scratch. “They can focus on their scenario and they don’t have to become PhDs in cryptography, we give them a simple platform to build their company on blockchain,”

Kaleido co-founder Steve Cerveny told CNBC recently.

Brexit-induced food inflation has lifted UK discounters

Bottom line maths

But it’s the numbers that tell the supermarket online story best: the global online grocery market was worth $98bn in 2015 according to International Data Group. That figure is expected to nudge $300bn by 2020.

Analyst Luca Solca is sector head for luxury goods at Exane BNP Paribas. Anticipating how global economic consumer trends play out is extraordinarily difficult he says. Future gazing can flatter consumers as rather more sophisticated creatures than the numbers, in the end, reveal.

He thinks blockchain is relevant for the luxury and fashion sector but wouldn’t be drawn on the tech’s impact elsewhere. It was the same with many other analysts OpenLedger approached. Even the British Retail Consortium (BRC) was non-committal – no research on blockchain’s impact had been done it said in a statement.

But National Farmer’s Union chief food chain adviser Ruth Edge is positive. She says blockchain has great potential for farm businesses, if supply chain progress is made.

Take a pig to market; four-day-old Oxford Sandy and Black new-borns

“Before this [blockchain take-up] can become a reality there needs to be greater provision of data across all levels of the supply chain,” she told OpenLedger. “We are seeing new ventures to improve the level of data available in the food and farming industry, such as the Government’s Livestock Information Service, and the NFU is keen to see more services like this.”

The business-to-consumer technology is still maturing

Big name interest

Part of the blockchain retail problem is down to the tech; public and private blockchains haven’t evolved at the same pace so some kind of convergence may help (Amazon’s Kaleido, based on ethereum, claims it’s attempting this).

Quietly, away from the limelight, Kraft Heinz, Kellogg, Johnson & Johnson, Reckitt Benckiser and a roster of independent consumer goods players are showing interest in INS’ ecosystem, the Russians claim.

Brands would be able to gather data on their consumers – they can’t currently because the supermarkets control access – “and use it to offer loyalty schemes to individual customers depending on their buying patterns”.

So far, so familiar, yet the technology under the bonnet is not. To survive, supermarkets may have to focus on the retail ‘experience’, increasingly wrapped in ‘wellness’ or ‘convenience’ or ‘inspiration’.

It’s the same across all retail, from car-buying to electronics as shopping transfers online. Why should milk and washing machine detergent – low margin, high volume, perfect for a ledger – be different?

Tesco’s problem are shared

Despite the invasion of German cheapies Aldi and Lidl – both worm £13 out of every £100 spent in UK supermarkets – Tesco’s profits soared almost 30% in 2018. Yet while Tesco’s profit margins are modest – scale is all – Britain’s biggest grocer is attempting to slash costs, close unprofitable stores and assets.

It’s desperate to improve market share, not to mention claw back a measure of share price respect after its humiliating 2014 £2bn accounting scandal, treating suppliers as sources of profit, and being exposed to £250m in fines.

Putting profit before pride, Tesco has even buddied up with French rival Carrefour to buy own-label products plus non-sale items, including trolleys and cleaning equipment, according to Money Week.

Tesco has joined forces with French multinational Carrefour on the costs front and is determined to be more profitable

The focus is utterly cost-driven. This month, Tesco announced it was launching Jack’s, it’s no-frills but desolate-sounding Aldi offshoot (no-frills products have higher margins and are a vital support for profits).

While the UK middle classes have taken up Aldi and Lidl with gusto, Jack’s “evokes desolate scenes of lonely shoppers peering at wilting produce, wondering if there are any aubergines,” Telegraph journalist Zoe Strimpel wrote recently.

Sainsbury’s is under similar pressure with its £51bn merger with Asda.

Post written by Adrian Holliday

Adrian has written about investing for 20 years, from Teletext to the Observer and AOL. He is a believer in diversity, low transaction costs and the future of fintech.

Follow OpenLedger!